IT’S 11.45 on a Saturday night in early August, 1960, and the attention of plain-clothes police officers is caught by an unusual sight in Glasgow’s Cathedral Square.

Two men, both in their thirties, were clambering over the railings surrounding the west enclosure of the square. They then approached the statue of King William III, took off their boots, and tried to climb the statue. Their mission: to find out whether the horse’s tail could actually move.

At Glasgow Central Police Court they pleaded guilty to having been disorderly in their behaviour. One of them said he had been drinking, and that he and the other man had been discussing whether the tail of the horse could shake.

The stipendiary magistrate asked how much drink had been consumed. “A few bottles of Guinness and a couple of whiskies”, came the solemn reply.

The men were fined £3, or 20 days.

As to whether the tail could move, the Evening Times said in its report of the court case that it could.

The statue was presented to Glasgow in 1735 by James Macrae who, according to the online Glasgow Story (theglasgowstory.com), made his fortune as the governor of the Presidency of Madras before returning to Scotland. “A firm Protestant”, it adds, “Macrae offered his statue as a memorial of ‘our glorious hero and deliverer (under God) from popery and slavery’.” The statue originally stood in front of the Tontine Hotel but became a traffic obstruction. In 1897 it was moved a short distance away to stand in front of the new Glasgow Cross railway station. In 1923 it began three years in storage before being taken to Cathedral Square.

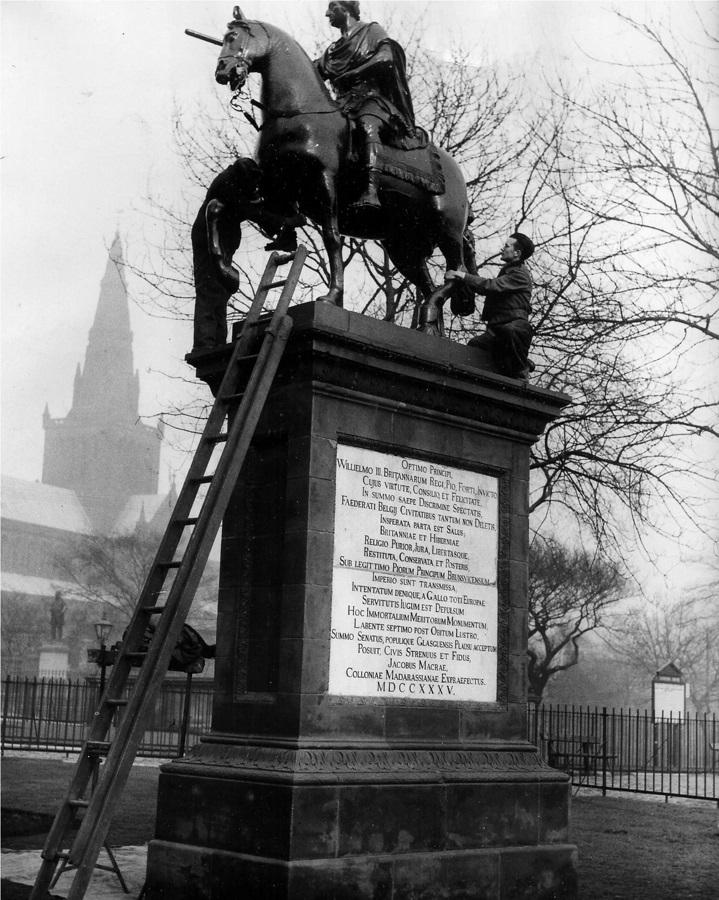

The statue is photographed (main image) in March 1951, receiving what was described as its first cleaning in 25 years.

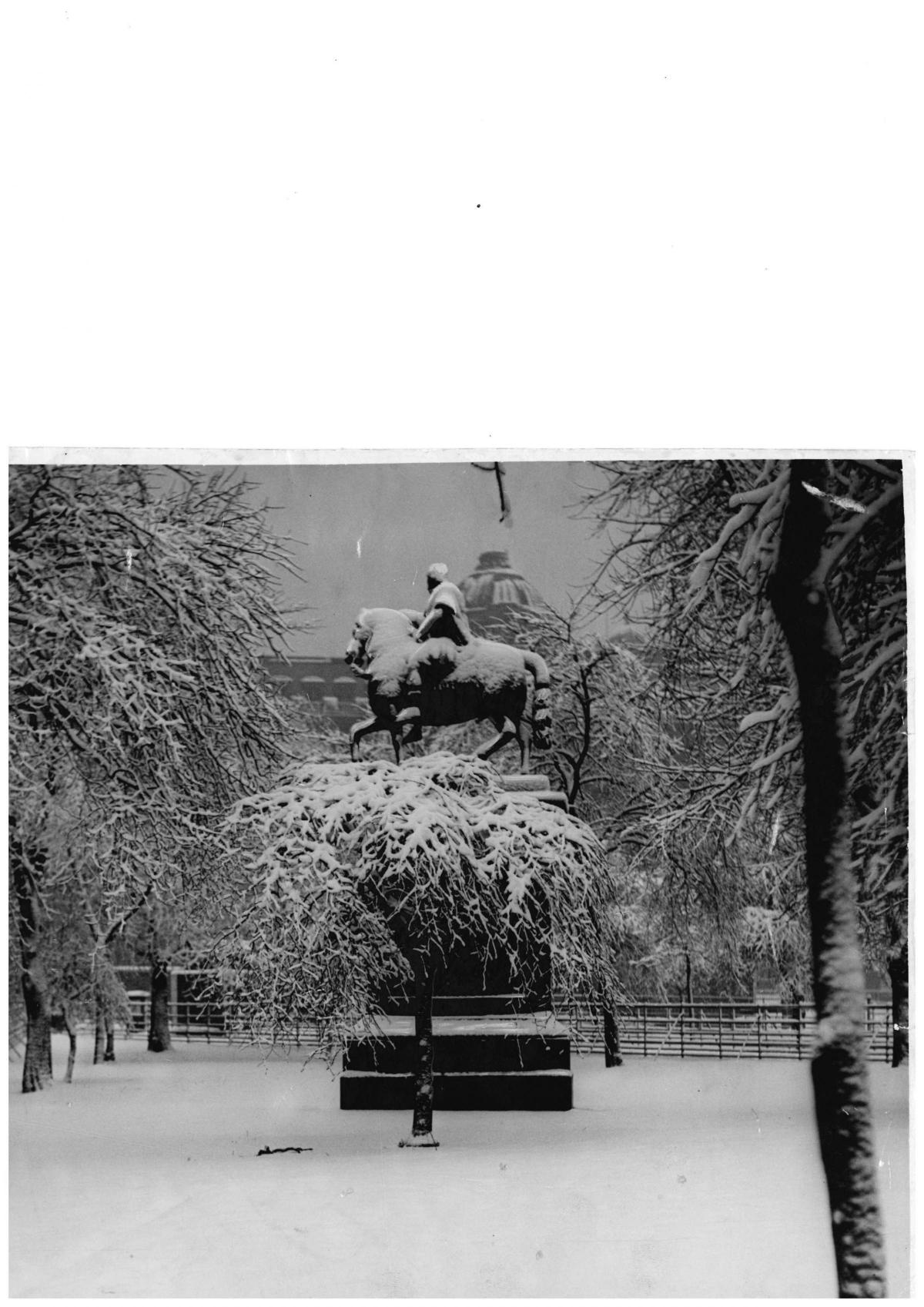

In the earliest years of the 20th century, Hogmanay gatherings traditionally took place at Glasgow Cross.

“Not for the first time in the history of these celebrations”, reported the Glasgow Herald of January 2, 1905, “King William’s statue became the target for empty bottles, thrown promiscuously into the air without respect for the safety of the public. Some of the missiles missed their mark and fell among the crowd, but others were smashed on the statue, the base of which in less than ten minutes was strewn with the fragments. By and by the people scattered, spreading din and disorder wherever they went”.

In 2018 Tom Shields, a name familiar to Herald readers, included the statue in his fine book, 111 Places in Glasgow That You Shouldn’t Miss, alongside the Barrowland Ballroom, the Grand Ole Opry, Cartha Rugby Club, the Arlington Baths, the Squinty Bridge and the Kelvin Hall. It’s not the only statue in the book: others include Lord Kelvin, Buffalo Bill and the Bud Neill Memorial.

Read more: Herald Diary

Why are you making commenting on The Herald only available to subscribers?

It should have been a safe space for informed debate, somewhere for readers to discuss issues around the biggest stories of the day, but all too often the below the line comments on most websites have become bogged down by off-topic discussions and abuse.

heraldscotland.com is tackling this problem by allowing only subscribers to comment.

We are doing this to improve the experience for our loyal readers and we believe it will reduce the ability of trolls and troublemakers, who occasionally find their way onto our site, to abuse our journalists and readers. We also hope it will help the comments section fulfil its promise as a part of Scotland's conversation with itself.

We are lucky at The Herald. We are read by an informed, educated readership who can add their knowledge and insights to our stories.

That is invaluable.

We are making the subscriber-only change to support our valued readers, who tell us they don't want the site cluttered up with irrelevant comments, untruths and abuse.

In the past, the journalist’s job was to collect and distribute information to the audience. Technology means that readers can shape a discussion. We look forward to hearing from you on heraldscotland.com

Comments & Moderation

Readers’ comments: You are personally liable for the content of any comments you upload to this website, so please act responsibly. We do not pre-moderate or monitor readers’ comments appearing on our websites, but we do post-moderate in response to complaints we receive or otherwise when a potential problem comes to our attention. You can make a complaint by using the ‘report this post’ link . We may then apply our discretion under the user terms to amend or delete comments.

Post moderation is undertaken full-time 9am-6pm on weekdays, and on a part-time basis outwith those hours.

Read the rules here