THE emergence of a novel pandemic, by its very nature, almost guarantees that there will be enormous practical difficulties for policy and, because (by definition) the science is uncertain, confusion about how best to act. That may be understandable and forgivable; even, perhaps, only to be expected in the opening stages of the crisis.

It is, however, hard to excuse such chaos when, 18 months later, it accompanies the gradual stages of lifting restrictions devised to cope with the disease. Those regulations were designed by public health officials and governments; some, such as the handling of care homes, were catastrophically mishandled; others, such as the development and roll-out of vaccines, went better than anyone might have reasonably anticipated.

But they all involved calculation and planning, which should have included an assessment of what might be expected to follow from their initial success or failure. What was predictable, almost to the point of inevitability, was that cases would rise when the very severe restraints imposed by lockdown were eased.

That is not, in itself, an argument against lifting restrictions (or we would be living with them forever). Indeed, the current situation, where a substantial rise in infections is not – thanks to vaccination – matched by the levels of hospitalisations, ICU treatment and deaths seen in earlier waves, shows that a cautious return to something like normality is probably justified, even if health – rather than the wider implications for the economy, liberties and social interaction – were the only consideration.

It should, however, have been blazingly obvious that a rise in cases, as society opens up and people begin to move around more freely, would also result in a rise in the number of people coming into contact with those who are infected. Vaccinations do not, after all, prevent transmission; they prepare the body for mitigating the worst effects of the disease when exposed to it.

The “pingdemic”, which has led to around 60,000 people in Scotland and 10 times that number in England and Wales being notified that they have potentially come into contact with someone who has tested positive was, therefore, something for which governments should have prepared.

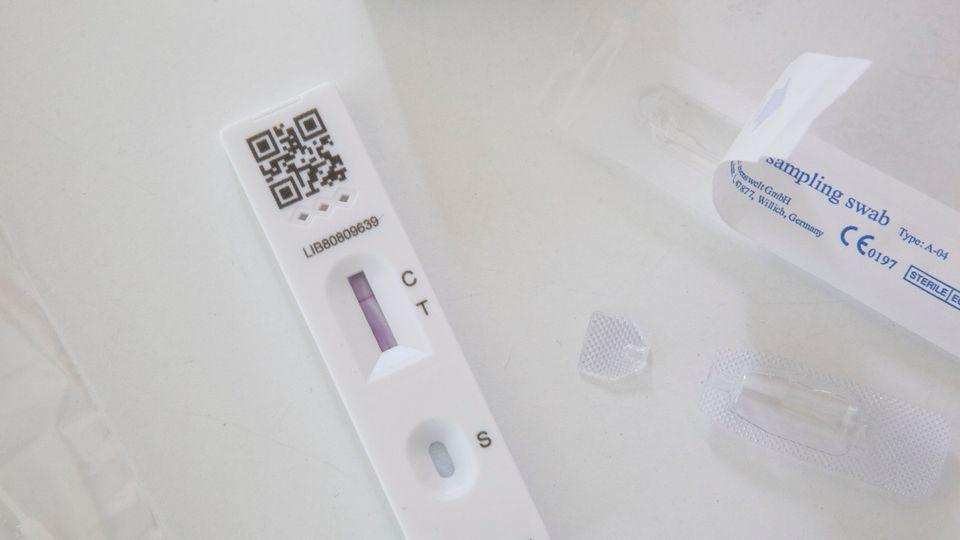

Though there is an undoubted, and worrying, rise in cases, many – in all probability a significant majority – of those advised to isolate for 10 days from the moment the government app gets in touch with them may not even have the virus. In fact, because of the ready availability of lateral flow tests, we know that this is the case.

The immediate result has been obvious, and seriously damaging to attempts to reopen the economy. Many firms, particularly small businesses, are effectively unable to operate because of a shortage of staff – even though many have taken tests and know that they are not infected. Though it should not be overstated, and is almost certainly a temporary blip, empty shelves in shops and staffing shortages in all sorts of key sectors are real enough. Unless the system changes, that will only get worse.

Unsurprisingly, many people are choosing simply to delete the Protect Scotland app and its English equivalent; an alarming development since, having been public-spirited enough to install it in the first place, they are likely to be the most responsible section of the community.

Isolation, like lockdown, is a blunt instrument. Before tests were readily available, it was the only real option. It still makes sense if, for example, someone in your household has tested positive; it is much harder to argue for the usefulness of quarantining people who can be tested instead, on the basis of possible proximity – in some cases, in huge venues such as supermarkets, within a 12-hour window.

Several pilot schemes that allow negative tests to end that requirement (much mocked when it was suggested, before they rapidly back-tracked, that the Prime Minister and Chancellor might take advantage of them) have in fact been running for weeks; it seems absurd that it should not be the default approach. It’s a serious failing that no one seems to have prepared for this entirely predictable problem; it’s one that must be sorted out immediately.

Why are you making commenting on The Herald only available to subscribers?

It should have been a safe space for informed debate, somewhere for readers to discuss issues around the biggest stories of the day, but all too often the below the line comments on most websites have become bogged down by off-topic discussions and abuse.

heraldscotland.com is tackling this problem by allowing only subscribers to comment.

We are doing this to improve the experience for our loyal readers and we believe it will reduce the ability of trolls and troublemakers, who occasionally find their way onto our site, to abuse our journalists and readers. We also hope it will help the comments section fulfil its promise as a part of Scotland's conversation with itself.

We are lucky at The Herald. We are read by an informed, educated readership who can add their knowledge and insights to our stories.

That is invaluable.

We are making the subscriber-only change to support our valued readers, who tell us they don't want the site cluttered up with irrelevant comments, untruths and abuse.

In the past, the journalist’s job was to collect and distribute information to the audience. Technology means that readers can shape a discussion. We look forward to hearing from you on heraldscotland.com

Comments & Moderation

Readers’ comments: You are personally liable for the content of any comments you upload to this website, so please act responsibly. We do not pre-moderate or monitor readers’ comments appearing on our websites, but we do post-moderate in response to complaints we receive or otherwise when a potential problem comes to our attention. You can make a complaint by using the ‘report this post’ link . We may then apply our discretion under the user terms to amend or delete comments.

Post moderation is undertaken full-time 9am-6pm on weekdays, and on a part-time basis outwith those hours.

Read the rules hereLast Updated:

Report this comment Cancel