ODD cove, Keir Hardie. As Labour’s leading person ever, I had to keep double-checking that he hadn’t become Sir Keir or Lord Hardie. What kind of Labour leader was this?

Well, this was a man of principle, reputedly the first working-class man in the House of Commons, an early supporter of Scottish home rule, staunch pacifist, and passionate believer in wealth distribution who died in poverty.

James Keir Hardie, Labour Party founder, was born on 15 August 1856, in a two-roomed cottage in Newhouse, Lanarkshire. His stepfather was a ship’s carpenter, his mother a domestic servant. He began work, aged seven, as a message boy for the Anchor Line Steamship Company. In the evenings, his mother taught him to read and write, skills which he later put to waste as a journalist.

Various other executive positions followed until, at the age of 10, he went down the pit, where he was employed to open and also close an air supply door. As he later recorded: “For several years as a child I rarely saw daylight during the winter months.” Mind you, in Scotland, even people on the surface could say that.

Later, thanks to the fantastic career prospects offered in mining, young Keir progressed to pony driver, hewer and quarrier. Outwith work, he became an evangelical preacher and downed lemonades with the temperance movement (his stepfather had enjoyed the occasional wee pick-me-up).

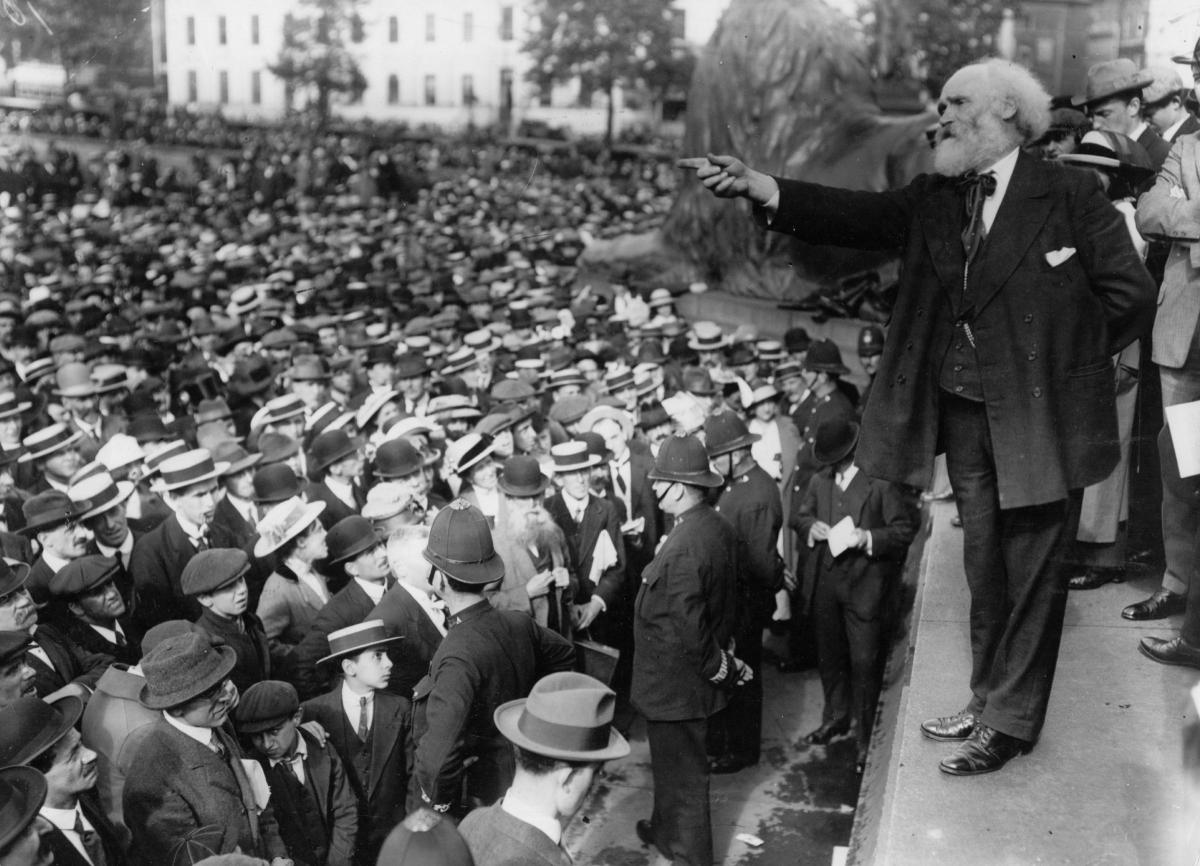

His religious hollerings gave him valuable experience of public speaking and, soon, he was asked to put his voice at the service of his fellow workers. As a result, he was blacklisted.

That didn’t deter him. Turning to journalism to make ends meet (good luck with that), he was also voted into various union leadership positions. Politically, he’d started off supporting the Liberal Party, which was then pretty pro-proletariat, but after police broke up a strike in Lanarkshire, he decided the working class needed its own party.

He first stood for parliament in the Mid-Lanarkshire by-election of 1888, as an independent, with this message for the electorate: “I ask you therefore to return to Parliament a man of yourselves, who being poor, can feel for the poor, and whose whole interest lies in the direction of securing for you a better and a happier lot.” As a result, he came last.

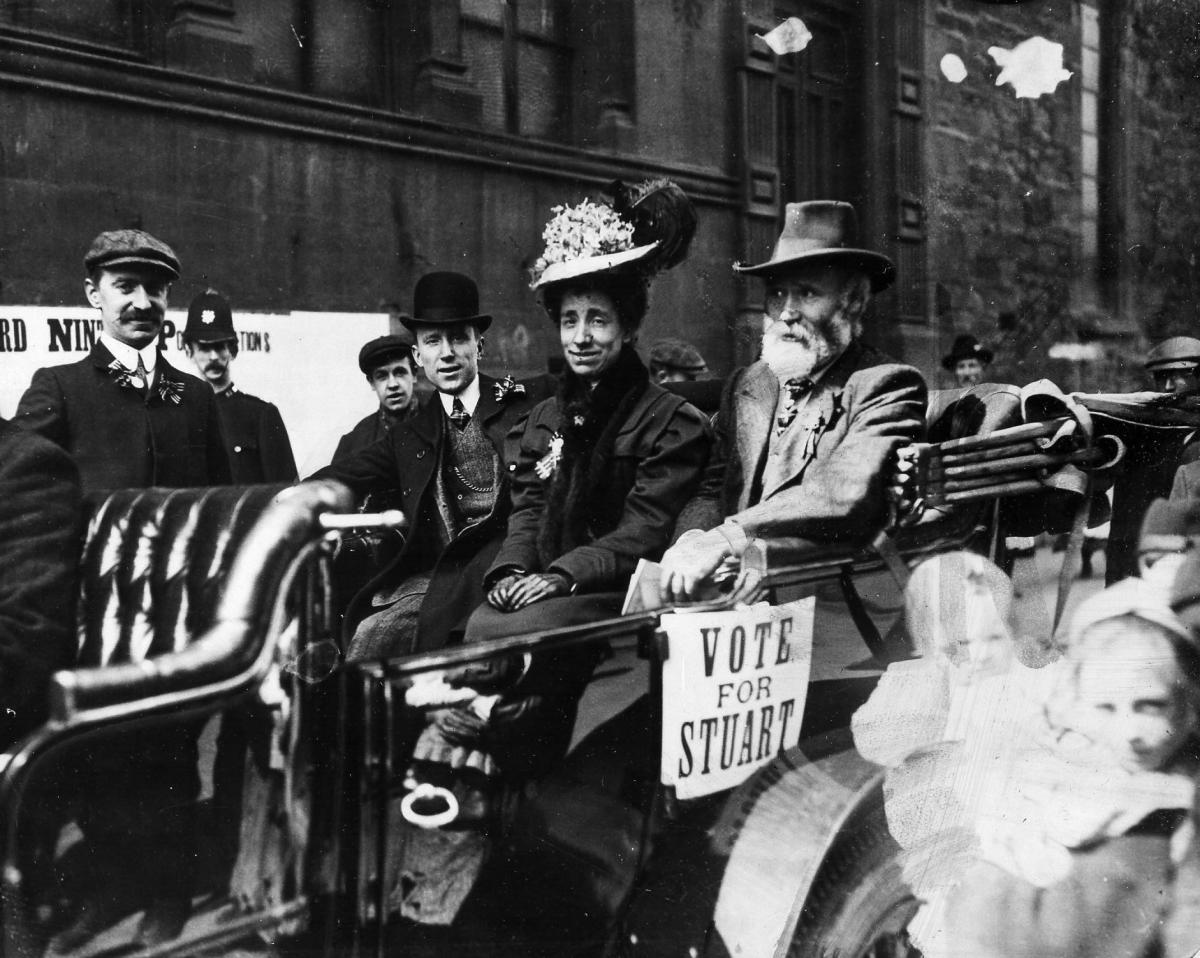

Later that year, in Glasgow, he formed the Scottish Labour Party with Robert Cunninghame Graham, who’d already been elected as Britain’s first socialist MP (standing under the Liberal banner) and who later founded the National Party of Scotland, forerunner of the SNP. As for Hardie, in 1892, he won a sensational result over the Tories in the Essex (now London) seat of West Ham South, standing as an independent.

Immediately, he caused a stooshie in Parliament: because of his claes. Abjuring the usual frock coat, top hat and wing collar, he opted for a tweed suit and deerstalker. The press went doolally, accusing him of – look away now, Martha! – wearing a cloth cap. Less outrageously, from the benches Hardie argued for a progressive income tax, pension rights, free education, votes for women, and abolition of the House of Lords. He was called “the member for the unemployed”, which he took as a compliment.

In 1893, he helped form the Independent Labour Party but, in 1895, lost his seat, partly because of a Commons speech lambasting the monarchy. Politics isn’t all about parliament, and he continued campaigning at home and abroad, with the San Francisco Call reporting a speech made about “socialism in England”, which is what Americans call Britain.

But Parliament called again when he was elected in 1900 for Merthyr Tydfil, in South Wales. By this time, though, he was having serious doubts about the Mother of Parliaments: "More and more the House of Commons tends to become a putrid mass of corruption, a quagmire of sordid madness, a conglomeration of mercenary spiritless hacks dead alike to honour and self-respect.” I see. As for the Lords, he said he’d “rather end than mend” it.

In 1900, he helped form the union-based Labour Representation Committee (LRC), which in 1906 became the Labour Party. In the 1900 election, the LRC, aided by a pact with the Liberals, won 29 seats. Hardie became Labour’s first parliamentary leader but, because of ill-health, resigned in 1908 in favour of Glasgow-born Arthur Henderson (whose sons became Baron Henderson and Baron Rowley).

He spent his remaining years campaigning for causes like women's suffrage, self-rule for India, and opposition to the First World War, which scarred his belief in brotherhood (“You have no quarrel with Germany”), particularly after he was shouted down by the patriotic proletariat.

It might be a stretch to say the heart was knocked out of him but, after a series of strokes, he died in 1915 in Glasgow. No tribute was paid to him in the Commons. A meeting in Glasgow to honour him attracted 5,000 people.

Warts and all: in an 1887 article for The Miner, Hardy criticised Glengarnock ironworks for importing Lithuanian labour “to teach men how to live on garlic and oil, or introduce the Black Death”. That same year, in a speech, he criticised their “filthy habits”. In 1889, at a Commons select committee, he complained about foreigners working in Scotland, saying: “Dr Johnson said God made Scotland for Scotchmen, and I would keep it so.”

However, he later recanted these views, speaking out against prejudice against foreigners, and advocating union rights for black workers in South Africa.

Another sensitive issue: home rule for Scotland. Hardie was a vice-president of the Scottish Home Rule Association, writing in 1889: “I believe the people of Scotland desire a parliament of their own …” This controversial view is played down in many biographical accounts, which engage in agonised contortions to explain it away as the Liberal idea of “home rule”, or federalism, and definitely not, you know, independence.

Who knows? Who cares? Despite some flaws, Keir Hardie was a great and selfless man. His name lives on today in British Labour’s current leader, the Oxford-educated QC, Sir Keir Starmer.

Our columns are a platform for writers to express their opinions. They do not necessarily represent the views of The Herald.

Why are you making commenting on The Herald only available to subscribers?

It should have been a safe space for informed debate, somewhere for readers to discuss issues around the biggest stories of the day, but all too often the below the line comments on most websites have become bogged down by off-topic discussions and abuse.

heraldscotland.com is tackling this problem by allowing only subscribers to comment.

We are doing this to improve the experience for our loyal readers and we believe it will reduce the ability of trolls and troublemakers, who occasionally find their way onto our site, to abuse our journalists and readers. We also hope it will help the comments section fulfil its promise as a part of Scotland's conversation with itself.

We are lucky at The Herald. We are read by an informed, educated readership who can add their knowledge and insights to our stories.

That is invaluable.

We are making the subscriber-only change to support our valued readers, who tell us they don't want the site cluttered up with irrelevant comments, untruths and abuse.

In the past, the journalist’s job was to collect and distribute information to the audience. Technology means that readers can shape a discussion. We look forward to hearing from you on heraldscotland.com

Comments & Moderation

Readers’ comments: You are personally liable for the content of any comments you upload to this website, so please act responsibly. We do not pre-moderate or monitor readers’ comments appearing on our websites, but we do post-moderate in response to complaints we receive or otherwise when a potential problem comes to our attention. You can make a complaint by using the ‘report this post’ link . We may then apply our discretion under the user terms to amend or delete comments.

Post moderation is undertaken full-time 9am-6pm on weekdays, and on a part-time basis outwith those hours.

Read the rules hereLast Updated:

Report this comment Cancel