Scottish Conservative MP

Born: April 18, 1937;

Died: September 20, 2017

SIR Teddy Taylor, who has died aged 80, was the nearly man of Scottish politics. Shadow Scottish Secretary since 1976, he helped Margaret Thatcher secure a modest revival in Scotland at the 1979 general election, but it was at the expense of his own Glasgow seat, depriving him of a place in the Cabinet which went instead to George Younger.

Although Taylor subsequently returned to the House of Commons as the MP for Southend-on-Sea, for some reason he escaped the Prime Minister’s preferment, something even more curious given that his politics – populist, Eurosceptic and socially conservative – were very much those of the Iron Lady and the Tory Party mainstream.

At the same time, Mrs Thatcher was aware of Taylor’s shortcomings. Irascible and inconsistent, he perhaps lacked the discipline for high office. Indeed, when Alick Buchanan-Smith resigned as Shadow Scottish Secretary in 1976, Taylor was Thatcher’s third choice as his replacement (she wanted Betty Harvie Anderson to become the Scottish Office’s first female shadow).

He was, however, in tune with his party leader when it came to devolution. The Scottish Conservative Party had been split since Ted Heath’s “Declaration of Perth” in 1968 and Taylor was on its sceptical wing. And although there was never a formal Shadow Cabinet vote to drop the party’s commitment to a Scottish Assembly it just, as Taylor later recalled, “quietly slipped away”.

Edward MacMillan Taylor was born in Glasgow on 18 April 1937. He hailed from a relatively poor but warm and tight-knit family, and Teddy (who signed the teetotaller’s pledge aged eight) was educated at the city’s High School. There, he organised a petition to have rugby replaced with soccer, and when he took over the school’s debating society, membership soared. At Glasgow University, Taylor joined the then Scottish Unionist Party.

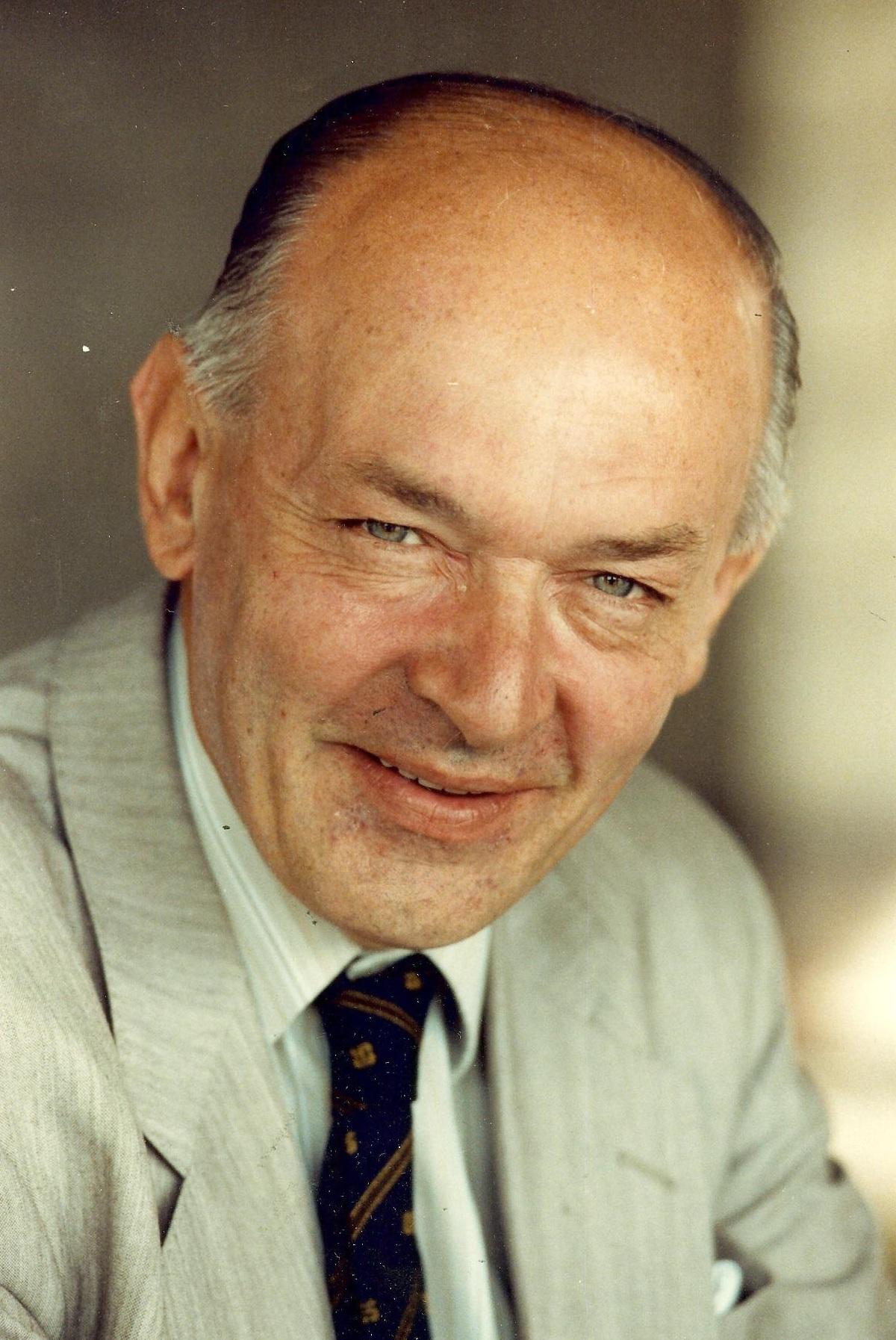

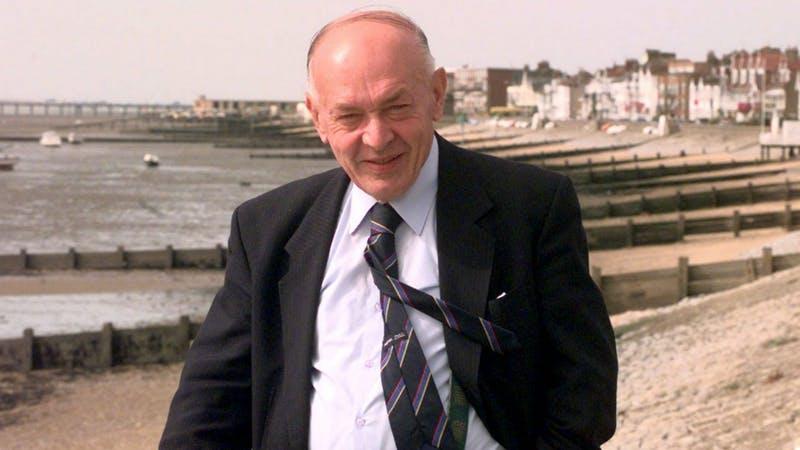

Former Conservative MP Sir Teddy Taylor, who has died (Peter Jordon/PA)

Following a short spell as a journalist on this newspaper, Taylor turned to politics, unsuccessfully contesting Glasgow Springburn at the 1959 general election, winning a place on Glasgow Corporation in 1960 and, at the 1964 election, becoming the MP for Glasgow Cathcart, the “baby of the House” at only 27. Hitherto a confirmed bachelor, he met Sheila Duncan after collapsing from exhaustion following several all-night sessions in the Commons (she was a social worker at the old Westminster Hospital). They married in 1970.

That same year Taylor was appointed Scottish Office minister for health and education by Prime Minister Edward Heath, but when the government decided to join the then European Economic Community, he quit the government in 1971. Taylor re-joined the party’s front bench three years later when Buchanan-Smith and his deputy Malcolm Rifkind resigned over Mrs Thatcher’s watered-down commitment to Scottish devolution.

At the 1979 general election, Mrs Thatcher secured more than 30 per cent of the Scottish vote and 22 MPs, a significant recovery after two decades of steady decline, but in Glasgow Cathcart, Taylor was defeated by 1,600 votes, losing to Labour’s John Maxton. When a by-election in Southend East gave him a route back to Parliament in 1980, he withdrew from the race to become rector of Dundee University in order to fight the Essex constituency.

Thereafter, Taylor focused his political energies on opposition to what would become the European Union. Active in the deeply Eurosceptic Monday Club, in 1992 he was one of the Conservative rebels who tried to thwart John Major’s Bill to implement the Maastricht agreement, something that earned him temporary expulsion from the Parliamentary Party. He had received a knighthood the previous year.

With a folksy, slightly rambling style, Taylor consistently supported the restoration of capital punishment (he sought leave to introduce a bill to that end in October 1974), use of the birch and a zero-tolerance approach to crime. Critical of Nelson Mandela during the Apartheid era, he later initiated contact with Libya during its period of isolation, meeting Colonel Gaddafi in 1991 and returning to the UK with a statement of regret over the killing of PC Yvonne Fletcher outside the Libyan Embassy in 1984.

Sir Teddy could be entertainingly other-worldly. In 1994, he appeared on the BBC comedy show Have I Got News for You, but appeared unaware of its irreverent intent, instead attempting to conduct a serious political debate with the other guests. He also used the show to announce that he was a fan of Bob Marley, which led to an invitation to present prizes at the British Reggae Awards a week later. With good humour, he accepted.

Although he stopped being a Scottish MP in 1979, on subsequent visits to Scotland Sir Teddy was still greeted with cries of recognition, although Southend had become his political and adopted home. In 2016, he campaigned there for Brexit, content, as his successor James Duddridge put it, that “he had seen the country come around to his way of thinking”.

Sir Teddy Taylor published a novel, Heart of Stone, in 1968, and a memoir, Teddy Boy Blue, in 2008. He died on Wednesday following a short illness and is survived by his wife Lady Sheila, their two sons and a daughter.

Why are you making commenting on The Herald only available to subscribers?

It should have been a safe space for informed debate, somewhere for readers to discuss issues around the biggest stories of the day, but all too often the below the line comments on most websites have become bogged down by off-topic discussions and abuse.

heraldscotland.com is tackling this problem by allowing only subscribers to comment.

We are doing this to improve the experience for our loyal readers and we believe it will reduce the ability of trolls and troublemakers, who occasionally find their way onto our site, to abuse our journalists and readers. We also hope it will help the comments section fulfil its promise as a part of Scotland's conversation with itself.

We are lucky at The Herald. We are read by an informed, educated readership who can add their knowledge and insights to our stories.

That is invaluable.

We are making the subscriber-only change to support our valued readers, who tell us they don't want the site cluttered up with irrelevant comments, untruths and abuse.

In the past, the journalist’s job was to collect and distribute information to the audience. Technology means that readers can shape a discussion. We look forward to hearing from you on heraldscotland.com

Comments & Moderation

Readers’ comments: You are personally liable for the content of any comments you upload to this website, so please act responsibly. We do not pre-moderate or monitor readers’ comments appearing on our websites, but we do post-moderate in response to complaints we receive or otherwise when a potential problem comes to our attention. You can make a complaint by using the ‘report this post’ link . We may then apply our discretion under the user terms to amend or delete comments.

Post moderation is undertaken full-time 9am-6pm on weekdays, and on a part-time basis outwith those hours.

Read the rules hereLast Updated:

Report this comment Cancel