Eighteen years after the US invaded Iraq, the country remains still largely divided along sectarian- ethnic lines and haunted by the spectre of the Islamic State group. Foreign Editor David Pratt journeyed across Iraqi Kurdistan meeting some of those facing off against each other

It’s been five years since I last met the general. Seeing him again now I’m struck by how little he has changed. The moustache, as ever, is immaculately manicured. His fatigues and desert boots are spotless – for now at least.

On his uniform, the shoulder patches depicting the flag of Iraqi Kurdistan and the word “Peshmerga” are reminders of the causes to which Major General Sirwan Barzani is devoted.

But it is not just warfare at which the general excels. Along the way he has become the managing director of Korek Telecom, a mobile phone operator in Iraq with seven million subscribers and estimated to be worth some $2 billion.

It is also worth pointing out that Sirwan Barzani is, of course, the nephew of the former president of Iraqi Kurdistan, Masoud Barzani, making him part of a political dynasty that has been at the centre of the semi- autonomous region’s politics for decades.

But it is neither business nor family that I’ve come to talk with the general about. As ever, our chat is about soldiering or, more specifically, the Peshmerga’s continuing fight against the Islamic State (IS) group. Eighteen years after the US invasion, Iraq today remains a place largely divided along sectarian and ethnic lines while the spectre of IS continues to haunt parts of the country.

The recent general election, the country’s fifth since the Americans were here, only served to underline Iraq’s precarious position with competing Shia parties at loggerheads following the outcome

With the Sadrist party of influential Shi’ite Muslim cleric Muqtada al-Sadr taking the most seats there was much anger among his rivals, notably the Iran-backed parties with links to militias accused of killing some of the 600 people who died in anti- government protests back in 2019.

Faultlines

While Iraq’s capital Baghdad and the country’s south around Basra remain locked in these inter-Shia rivalries, elsewhere in the Kurdistan region of the north there are other faultlines shaped by the region’s volatile politics.

General Barzani and his Peshmerga fighters sit on one side of such a faultline facing off as they do against the continued threat of IS and acting as a bulwark against the growing influence in the region of the powerful Iranian-backed Hashd al-Shaabi, sometimes known as the Popular Mobilisation Forces (PMF).

Hashd itself is the umbrella organisation for the pro-Iranian Shia groups that have grown in power in Baghdad and the south and is viewed by many Iraqis – especially Kurds – as an instrument of Tehran’s foreign policy in the region.

It was not Hashd al-Shaabi, however, but the continuing threat of the jihadists of IS that was preoccupying the mind of General Barzani the day we met.

Just like the last time, our rendezvous was at the base of the “Black Tigers”, the name given to Barzani’s crack Peshmerga unit billeted near the Iraqi Kurdish town of Makhmour.

That name, Barzani tells me, comes from the radio call sign he used many years ago when he and his Peshmerga fought a more than decade-long guerrilla campaign against Saddam Hussein’s regime from Kurdistan’s mountains.

As we talk, he takes me on a tour of the base which is as spotless and well-manicured as the general is himself.

Only the rusting hulks of a handful of ramshackle vehicles tarnish the apron of the parade ground, all of them resembling something from a Mad Max movie.

“My collection,” Barzani announces, walking over to the vehicles captured by his Black Tigers from IS before they were put to deadly use as armoured car bombs for suicide attacks.

Before us sat a cluster of customised pick-up trucks and saloon cars, their box-like angular shape bringing to mind a child’s drawing of a car and a result of the jumble of welded or bolted-on metal plates designed to protect the driver before he delivers his deadly payload and blows himself and his victims to oblivion.

‘One way trip’

ON the door of one deadly wagon, Barzani shows me the stencilled insignia indicating a specific IS unit then turns to another which he explains has a very special feature involving a hatch that would have been bolted down from the outside once the driver was inside. “It’s what you might call a guaranteed one-way trip,” Barzani tells me, a grin breaking out across his face.

Ten minutes later, we are in a vehicle convoy of his own heading for one of the most strategic positions in the region that sits atop nearby Makhmour mountain.

As our cluster of jeeps turns off the main highway onto a dirt track that spirals up around the mountainside, I notice that front and back we are joined by two pick-ups trucks, each of which have heavy machine guns mounted and are packed full of Kalashnikov carrying Black Tiger Peshmerga.

Earlier in our talk the general had warned how IS are still very much active in this area and our additional escort, along with Barzani’s own bodyguards kitted out with state-of-the-art weaponry, was a measure of how seriously the general took that threat.

For much of the outside world the jihadists of IS might seem a thing of the past, a spent force after their ousting from the Iraqi city of Mosul and collapse of their so-called caliphate in neighbouring Syria.

But over the course of my recent time in northern Iraq, especially in and around Mosul’s old city on the West Bank of the Tigris River, the bomb-blasted ruins stand as a stark reminder of the battle to defeat IS which was considered the toughest urban warfare since the Second World War. With Mosul’s liberation it was hoped that IS would shrivel and die – but nothing could be further from the truth.

Passing through tiny hamlets on the way to the summit of Makhmour mountain it was a sobering thought that here, all around us, members of active IS cells are still operational.

The landscape itself was worthy of such a sinister presence. It was a bleak, parched, forbidding place, the track up which we journeyed engulfing us in dust forcing the vehicles to occasionally pause to allow the dun-coloured cloud to clear for fear of plummeting hundreds of feet down the sheer mountainside drops that flanked the road.

Once on top, ensconced behind sandbagged fortifications and surrounded by mortar emplacements, General Barzani explained the lie of the land beneath us.

He told, too, of how anywhere up to 200 IS members were active in the terrain below, setting roadside bombs, or setting up fake checkpoints dressed as Kurdish policemen or security forces before kidnapping locals for ransom.

“This is the Tora Bora of Iraq,” Barzani explained, referring to the cave complex in eastern Afghanistan which Osama bin Laden’s own jihadist fighters of al-Qaeda had made their own last redoubt.

‘Bump into IS’

In what had been long day and with the light fading fast over Makhmour mountain, Barzani departed to visit another nearby frontline position, giving an assurance that his men would escort me back to the comparative safety of the main highway. “I would not stay too long before leaving,” Barzani politely warned as he waved goodbye and I continued to take photographs. “If you do, then with the darkness there is a real chance that you will bump into IS on the way down.”

Barzani’s “Black Tigers” are, of course, far from the only Peshmerga fighters to have come face to face in battle with IS. Just a few days after my encounter with the general, I found myself again in the mountains of the Kurdistan region, this time in Kirkuk province in the company of women from the Kurdistan Freedom Party (PAK)

As a Kurdish nationalist group PAK comprises mainly of Iranian Kurds who are integrated into Iraqi Kurdistan’s Peshmerga forces.

With their eyes on the prize of a free greater Kurdistan, the women and men of PAK have found themselves fighting along a number of Iraqi Kurdistan’s faultlines these past years.

First and foremost, all are exiles from Iran whose regime they oppose and regard as their major enemy.

But in recent times the fight against IS, which remains active, has taken priority. When not fighting the jihadists, the women of PAK have also found themselves in battle against the Iranian-backed Shia militia Hashd al-Shaabi, whom they regard as a weapon of Tehran’s ambitions in Iraq and presenting as big a threat as that of IS.

Sarbakho and Atusa are two of the women among scores that I was to meet at a mountain camp where daily they undergo firearms, fitness and hand -o -and combat training.

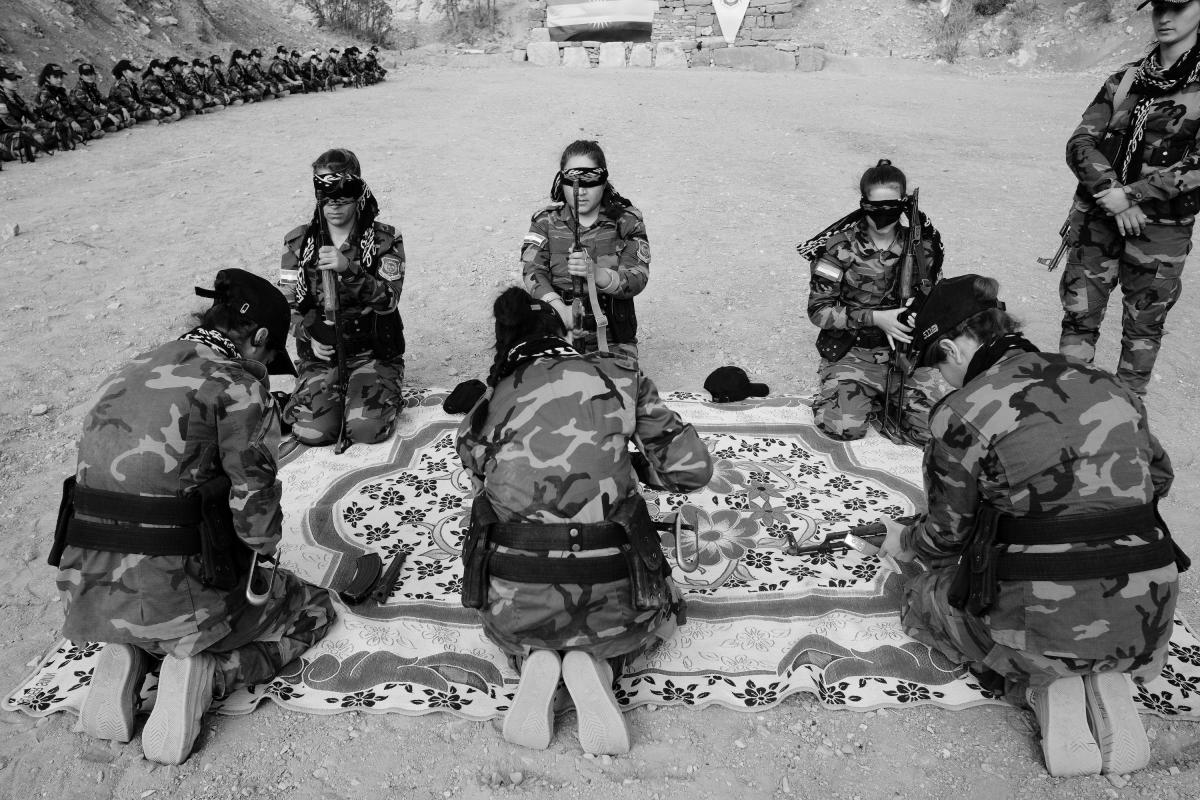

“I have seen frontline combat against both IS and Hashd al-Shaabi, and seen comrades die for our cause,” Atusa tells me, as around us other women in the unit practice stripping down and putting back together again their Kalashnikov assault rifles while blindfolded.

This is not simply a show for the cameras but part of a rigorous daily routine that has resulted in the women of PAK having a fearsome reputation as frontline fighters. Some PAK members are known to have travelled to Syria where they helped defend the city of Kobani against IS when the jihadists laid siege to it back in 2014.

“This is our life, we have given everything for the fight for a Kurdish homeland,” says Sarbakho, who goes on to explain that many of the women have their families with them here in the camp and adjacent compound where they live together.

‘Terrorists’

EACH and every member of PAK knows that to return to Iran would mean certain death where the authorities in Tehran considers them “terrorists”. In view of this it’s perhaps hardly surprising that PAK sees Hashd al-Shaabi as much of a threat as IS and has on numerous occasions fought pitched battles with them along Iraqi Kurdistan’s political faultlines.

For their part, Hashd al-Shaabi see PAK as little different from IS who they, too, have also been in the forefront of defeating. That much was made clear when I visited one of the group’s headquarters close to the village of Badoush, in the Nineveh Governate north west of the city of Mosul.

Driving up to the headquarters past the main gate, a long avenue is lined with photographs of 42 Hashd al-Shaabi martyrs or “shahid” who lost their lives fighting IS in the area.

Dotted around there are giant posters of Iran’s most powerful military commander, General Qassem Soleimani, the Commander of the Quds Force of the Iranian Revolutionary Guard Corps, and Abu Mahdi al-Muhandis, the senior commander of Hashd al-Shaabi, who were both assassinated in a US air strike last year that set alarm bells ringing across the region and wider world.

Haji Abu Turab Al Hilali is deputy commander of Hashd al-Shaabi in Nineveh Governate and explained to me their role in the area.

“We came here to fight the terrorists of IS and that job is not yet over, but we, Hashd al-Shaabi, also work to help rebuild the local community after the war,” Al Hilali tells me as his heavily-armed men gather round to hear their commander speak. A slight man, he is serious in demeanour and dressed in the familiar all-black uniform of the Shia militias. It’s only when a US Chinook and Blackhawk helicopter pass high overhead that the mood lightens.

“The Americans,” Al Hilali says, pointing skywards with a smile, “perhaps they are coming here for us.”

All joking aside, however, it is the growing presence of Iran through militias like Hashd al-Shaabi that is seriously giving Washington cause for concern.

That Hashd’s presence is resented by a growing number of Iraqis, especially Kurds who view their role as little more than a determined effort to extend Iran’s influence in their country, does not bode well for the future.

For now, such faultlines across Iraq’s political landscape remain largely dormant with only the occasional flare-up between rivals like Hashd al-Shaabi and their Kurdish and other opponents in Baghdad and elsewhere.

But as the recent election acrimony revealed, tensions simmer menacingly and the threat of them boiling over is forever real.

It’s a situation that suits the ever-lurking and malign presence that is IS who are slowly rebuilding albeit in a more shadowy guise.

Almost two decades on from the US invasion, Iraq remains divided and provides the arena for new proxy battles being fought or about to be fought by myriad players.

Those faultlines, worryingly, continue to grow.

Why are you making commenting on The Herald only available to subscribers?

It should have been a safe space for informed debate, somewhere for readers to discuss issues around the biggest stories of the day, but all too often the below the line comments on most websites have become bogged down by off-topic discussions and abuse.

heraldscotland.com is tackling this problem by allowing only subscribers to comment.

We are doing this to improve the experience for our loyal readers and we believe it will reduce the ability of trolls and troublemakers, who occasionally find their way onto our site, to abuse our journalists and readers. We also hope it will help the comments section fulfil its promise as a part of Scotland's conversation with itself.

We are lucky at The Herald. We are read by an informed, educated readership who can add their knowledge and insights to our stories.

That is invaluable.

We are making the subscriber-only change to support our valued readers, who tell us they don't want the site cluttered up with irrelevant comments, untruths and abuse.

In the past, the journalist’s job was to collect and distribute information to the audience. Technology means that readers can shape a discussion. We look forward to hearing from you on heraldscotland.com

Comments & Moderation

Readers’ comments: You are personally liable for the content of any comments you upload to this website, so please act responsibly. We do not pre-moderate or monitor readers’ comments appearing on our websites, but we do post-moderate in response to complaints we receive or otherwise when a potential problem comes to our attention. You can make a complaint by using the ‘report this post’ link . We may then apply our discretion under the user terms to amend or delete comments.

Post moderation is undertaken full-time 9am-6pm on weekdays, and on a part-time basis outwith those hours.

Read the rules hereLast Updated:

Report this comment Cancel