IT’S 16 years since I told the story of Binyam Mohamed, and how British intelligence shadowed him through the gulags of the War on Terror. Britain was there in Karachi when he was tortured; British spies fed questions to Moroccan torturers who took a scalpel to his penis; they watched as he was dragged to an American torture chamber in Afghanistan and then to the camp at Guantanamo.

Britain was neck-deep in the worst, most criminal, aspects of America’s War on Terror. As Tony Blair said, we stood shoulder to shoulder with America no matter what its government did. Today, though, there’s moves within America to admit the shameful crimes Washington carried out in the name of democracy. In London, there’s no such contrition.

America still runs Guantanamo – an act which itself should be enough to disbar any nation from claiming to be a democracy. However, last week, while the world had its eyes fixed on COP26, a small but important event occurred. Seven senior US officers serving on a military jury chose to describe the torture of terror suspects by the CIA as “a stain on the moral fibre of America”.

The comments related to the treatment of Majid Khan, an al-Qaeda courier who’s been in custody since 2003. He was beaten, waterboarded and kept chained in the dark. Khan, who says he made up lies to appease his interrogators, was sentenced to 26 years. However, in a letter urging clemency seven of an eight-member military jury denounced the torture of Khan. His treatment, they said, “in the hands of US personnel should be a source of shame for the US government”. Khan, who has cooperated with US officials since admitting his guilt, may now be released as early as February after nearly two decades in captivity.

Read more: British state colluded in the murder of its own citizens. Where’s the justice?

It may not seem much, but the condemnation of American torture on moral grounds by those US military officers goes a hell of a lot further than anything that’s happened in the UK. Britain has never apologised, never admitted.

I investigated British complicity in the criminal extremes of the War on Terror for years throughout the first decade of this century. Assisting in extraordinary rendition – that’s a cosy term for kidnapping suspects off the street and disappearing them into Black Site prisons – was just the very tip of the iceberg. British airports, including Glasgow and Prestwick, were used for refuelling by CIA planes carrying kidnapped suspects.

Britain’s collaboration ran much deeper than logistics. Let’s go back to the story of Binyam Mohamed. His case reveals the payback British intelligence got for assisting in extraordinary rendition: our spies were able to question suspects like Mohamed by proxy – the proxy being a foreign torturer.

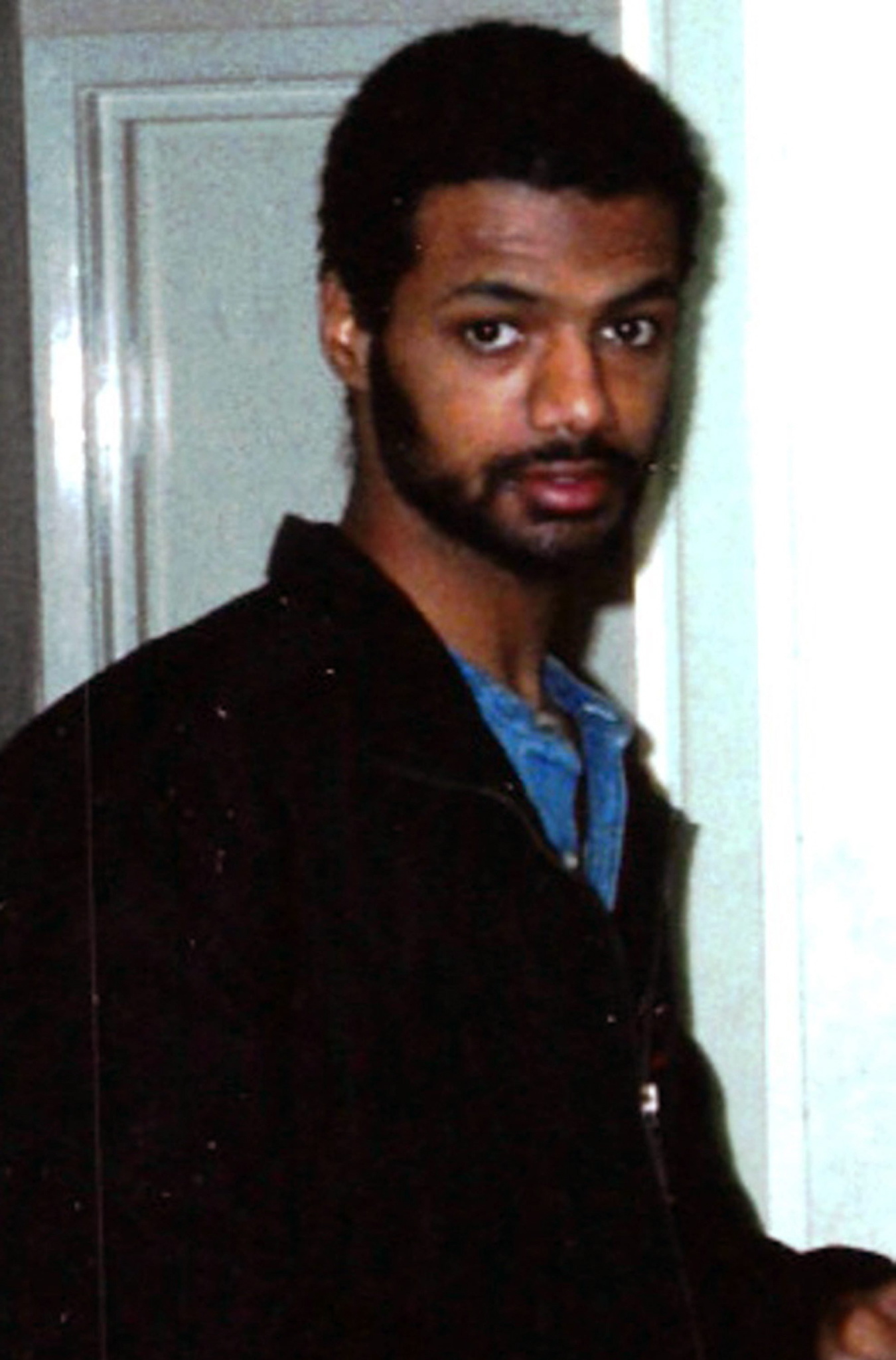

Binyam Mohamed

Mohamed was born in Ethiopia but came to Britain as a teenager seeking asylum. He got mixed up in drugs in London and eventually ended up travelling to Afghanistan, then under Taliban rule. After 9/11, he was attempting to make his way back to Britain when he was seized at Karachi airport as a terrorist suspect.

Mohamed was tortured by Pakistani guards and later visited by FBI agents who told him if he didn’t start talking he’d be taken to an Arabic country where things would get worse. His torture at the hands of Pakistani guards continued. Two British intelligence officers came to interrogate him. They gave him tea with two sugars – Mohamed said he only took one sugar but they added: "No, you need a lot more. Where you’re going, you need a lot of sugar." MI6 claims its officers never interrogated Mohamed. However, MI5 did admit one of its officers spoke to Mohamed while he was in Karachi.

Mohamed was moved to another facility in Pakistan where he was handed to the CIA. He was stripped naked, had a suppository forcibly inserted, then was dressed in a jumpsuit, shackled, blindfolded, with ear defenders over his head, strapped into a plane and flown to Morocco.

In Morocco, Mohamed suffered appalling, medieval abuse. One of his interrogators said "the Brits sold you out to us". Mohamed insists that the questions asked of him during his time in Morocco could only have come from British intelligence. In other words, British intelligence is accused of passing information to interrogators in Morocco used during Mohamed’s torture. In Morocco, a woman who identified herself as Canadian spoke to him. She threatened him with rape and electrocution and produced what she called her "British file" with pictures of UK residents the interrogators wanted to know about.

Mohamed was beaten brutally by guards until he lost consciousness. This went on for days. Later, his chief interrogator took a scalpel and used it to cut Mohamed’s penis. “They cut all over my private parts,” Mohamed said. “One of them said it would be better just to cut it off as I would only breed terrorists.” Guards threatened to rape him and also sexually assault him with a broken bottle. He was drugged, deprived of sleep for days on end, made to listen to blaring rock music and the soundtrack to pornographic movies. After 18 months in Morocco, he was moved to a Black Site prison in Kabul. He was kept in the dark and hung from the ceiling by his CIA interrogators. In 2004, Mohamed was flown to Guantanamo Bay where he continued to suffer mistreatment including beatings and denial of medical care. He was eventually released and sent back to the UK in February 2009.

In November 2010, Mohamed received an undisclosed sum as compensation from the British government as part of a settlement with around a dozen men who accused the UK’s security forces of collusion in their rendition and torture. At the time, then Foreign Secretary William Hague denied the deal was an admission of guilt but reflected a desire to “move on”.

Mohamed is just one case. There are many more. If the US military can now find the moral courage to admit its sins, then Britain too must have the gumption to confess to such crimes. To fail to do so is – as those American military jurors warned – to ingrain the stain on the moral fibre of this nation.

Our columns are a platform for writers to express their opinions. They do not necessarily represent the views of The Herald

Why are you making commenting on The Herald only available to subscribers?

It should have been a safe space for informed debate, somewhere for readers to discuss issues around the biggest stories of the day, but all too often the below the line comments on most websites have become bogged down by off-topic discussions and abuse.

heraldscotland.com is tackling this problem by allowing only subscribers to comment.

We are doing this to improve the experience for our loyal readers and we believe it will reduce the ability of trolls and troublemakers, who occasionally find their way onto our site, to abuse our journalists and readers. We also hope it will help the comments section fulfil its promise as a part of Scotland's conversation with itself.

We are lucky at The Herald. We are read by an informed, educated readership who can add their knowledge and insights to our stories.

That is invaluable.

We are making the subscriber-only change to support our valued readers, who tell us they don't want the site cluttered up with irrelevant comments, untruths and abuse.

In the past, the journalist’s job was to collect and distribute information to the audience. Technology means that readers can shape a discussion. We look forward to hearing from you on heraldscotland.com

Comments & Moderation

Readers’ comments: You are personally liable for the content of any comments you upload to this website, so please act responsibly. We do not pre-moderate or monitor readers’ comments appearing on our websites, but we do post-moderate in response to complaints we receive or otherwise when a potential problem comes to our attention. You can make a complaint by using the ‘report this post’ link . We may then apply our discretion under the user terms to amend or delete comments.

Post moderation is undertaken full-time 9am-6pm on weekdays, and on a part-time basis outwith those hours.

Read the rules hereLast Updated:

Report this comment Cancel