Moves are under way to grant pardons and issue apologies to the thousands killed during the ‘Satanic Panic’ which reached its peak in Scotland in the 1600s. To find out what really happened, and why we should commemorate these grisly events, our Writer at Large Neil Mackay speaks to Scotland’s leading witchcraft scholar Professor Julian Goodare

THERE is a debate bubbling away in Scottish society – like some magical potion in a smoking cauldron set to simmer – about how we come to terms with one of the most disturbing episodes in our history: the execution of about 2,500 people, mostly women but some men too, as witches.

Scotland was the most ferocious country in Europe when it came to witch-hunting, killing far more people proportionally than any other nation.

Today, there’s talk of apologies and memorials for those who lost their lives. The Scottish Government looks set to address this legacy of the past with legislation to pardon victims. Just this wee, Catalonia pardoned those executed as witches centuries ago.

But what do we in Scotland really know about this dreadful part of our history beyond the bare facts?

The true story of the Scottish witch hunts is even more astonishing than we imagine – upending popular misconceptions, and showing that much of what we think to be true is simply myth. In some respects, we modern Scots are just as confused about witches as our religious forebears.

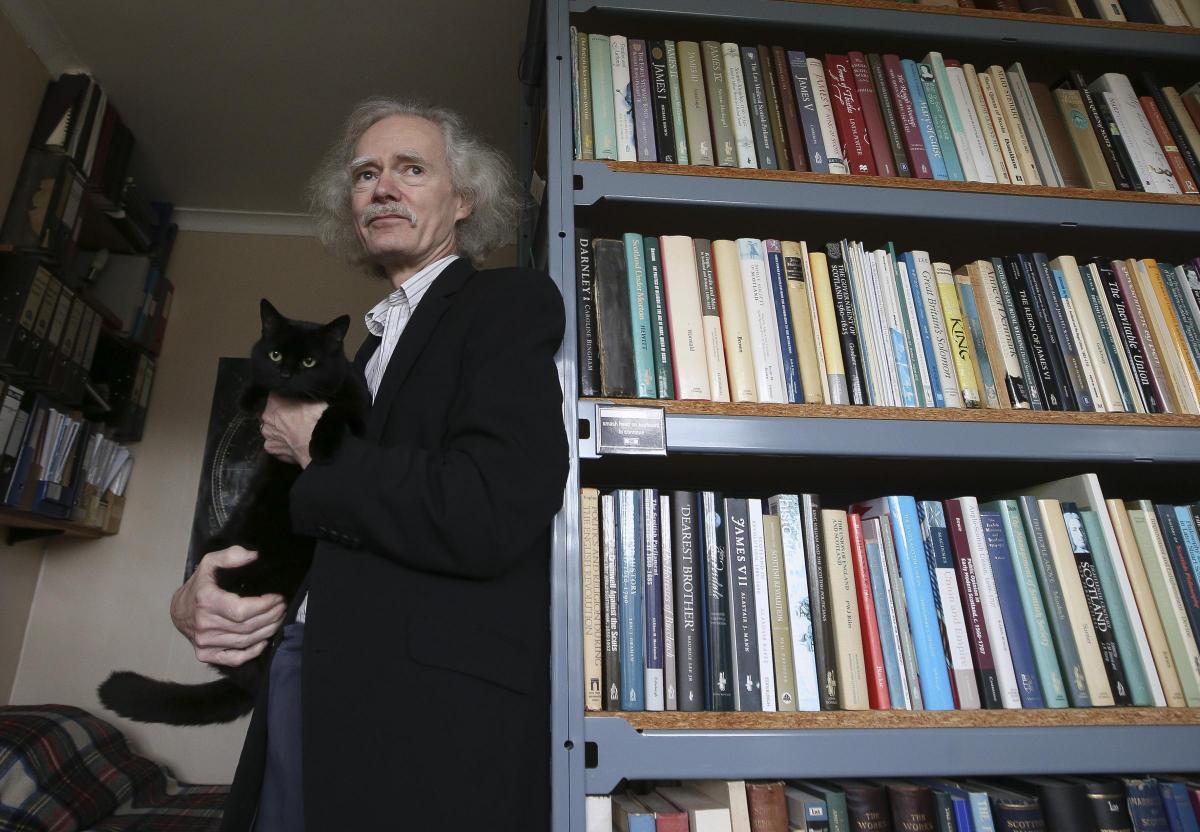

To get to the truth of what really went on in the 16th, 17th and even the early-18th century, The Herald on Sunday has turned to Scotland’s leading scholar on the witch hunts: Professor Julian Goodare from Edinburgh University.

He is director of the Survey of Scottish Witchcraft, and has published several books on the “Satanic Panic” which gripped the country from the end of the 1500s, including Scottish Witches And Witch-Hunters, Witchcraft And Belief In Early Modern Scotland, and The European Witch-Hunt.

How did it start?

SURPRISINGLY, witch-hunting wasn’t a “craze” in the Middle Ages, the medieval period. It took until the late-16th and early-17th century (well into what historians call the early modern period) for the hunts to really get going.

However, the medieval era did lay the foundations for the persecution to come.

The 1400s saw numerous heresies ignite across Europe – like the Lollards in England or the Hussites in Bohemia, which challenged the Catholic Church. So, during the Middle Ages, “there’s lots of worry about heresy and heretics” on the rise, Goodare explains.

Then comes Luther and the Protestant reformation, focused on keeping rigidly to the teachings of scripture.

Anyone seen acting contrary to the Bible could find themselves in serious trouble.

Crucially, says Goodare, the witch hunts also overlapped with a “rise in state power – and religion was part of that state power”. As European society advanced, there was just “more government” and the Bible was central to the way rulers ruled.

So, the reformation and “big government” collided, creating a set of circumstances where “state authorities were trying to prove they’re godly … This is where frenzies can develop. If you could draw a graph of the rise of witch-hunting and of the rise of state power they would run roughly together”.

Religion was also public. Everyone was Christian and if you stepped out of line “you’d be in trouble”.

In Scotland, control was maintained by the Kirk Session, which could drag parishioners in for questioning and dole out punishment for offences of “fornication” or “breaching the sabbath”, with penalties like small fines and public shaming.

Targeting people for witchcraft “was much rarer”, Goodare explains. However, it is the Kirk Session – run by local ministers and elders, mostly wealthy tenant farmers – which predominantly initiated witch trials. “They do the initial information gathering. They can interrogate the person or gather information from neighbours.”

Torture was also used. Once the Kirk considered someone a witch, the accused was passed upwards to “secular criminal courts”.

Who did they burn?

GOODARE points to two types of witches targeted: the “village witch” and the “demonic witch”.

“The village witch is someone thought to have bewitched their neighbours,” he says. The village witch is usually caught in a scenario like this: two neighbours quarrel, insults and threats are exchanged, and then one of the neighbour’s cows dies or even their child. Suspicion immediately falls on their “enemy” as a witch.

“Witchcraft trial records are full of stories like that,” Goodare says. To the average person in the 1600s, this cause and effect equation made complete sense: Person X hates Person Y; something bad happens to Person Y; so Person X must be a witch.

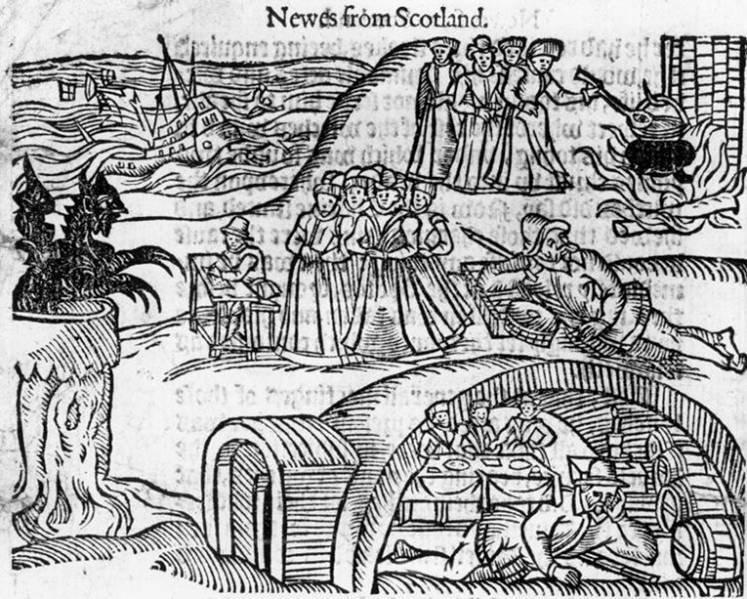

Of greater interest, though, to the authorities was the demonic witch – “someone who’s made a pact with the Devil”. A good example would be the infamous North Berwick witches, accused of plotting with Satan to kill King James VI of Scotland, later James I of England.

It was a sensation in 1590, turbo-charging the witch panic. The case probably inspired Shakespeare to invent the witches in Macbeth, a play staged for James, who was fascinated by witchcraft.

Once someone was targeted as a village witch it was relatively easy for the case to snowball into the much more serious offence of being a demonic witch.

If someone is hauled before the Kirk for bewitchment, the authorities would check if the accused was up to something more dangerous – like working with the Devil. So, questions are asked, torture used … and prisoners, inevitably, confess to meeting Satan. To understand just how terrifying the idea of a pact with Satan could be, Goodare says we need to put ourselves in the shoes of the average 16th-century villager.

They believed wholeheartedly in demons – and the notion of fellow humans working with the Devil was an “horrific scenario”. This fear of a “subversive conspiracy, in league with the Devil, wasn’t really present in the Middle Ages”. But once this new idea took off, it turned into mass panic. King James even writes a book called Daemonologie in 1597. Imagine if a politician today wrote a bestseller pinpointing some “enemy within” and what the results might be?

There were claims that witches were killing and eating babies. Goodare draws comparisons to the “Satanic Panic” of the 1980s when false allegations were made around the world of people involved in ritual child abuse. It is key to remember, though, says Goodare, that the witch-hunters were “sincere, not cynical” – they weren’t making up allegations, they really believed they were fighting evil.

Paganism and finger pointing

THERE’S a popular belief that many victims were deliberately falsely accused by their enemies. What better way to punish a rival than accuse them of witchcraft? However, that idea just doesn’t stand up to scrutiny, says Goodare. The people accusing others of being witches really believed that those they were naming were in league with Satan or practising black magic.

There has also been a persistent belief that many victims were practising pagans, not devil-worshippers, and religious authorities at the time just mixed up one for the other. Not so, says Goodare. “The idea that these people were consciously pagan really has no traction in credibility. They all thought they were Christians.”

However, he adds: “You do find people who, although they think they’re Christian, practise things I’d be comfortable calling ‘magic’ … These are people we might think of as ‘folk healers’. You’ll find people like that in most traditional societies in Europe in the early modern period.”

Ironically, the charms they created would often involve prayers addressed to God.

In the Middle Ages, these healing practices weren’t a big problem, but come the late 1500s and the reformation “the people trying to clean up Christianity were going ‘wait a minute, the Bible doesn’t tell you do that, this is wrong’.”

Mental illness

GOODARE thinks a lot more work needs to be done between psychologists and historians investigating the mental state of both accusers and accused during the witch hunts. Although he says he doesn’t really see evidence of autism in trial records, there’s a chance, he believes, of autistic people perhaps confessing to crimes they didn’t commit. However, this remains impossible to prove retrospectively.

Some accusers may have suffered from other mental health problems. Extreme attention-seeking is connected to mental illness. In 1697, a wealthy 10-year-old girl, Christian Shaw from Renfrewshire, was said to be “vomiting coal and bent pins”. Seven people accused of bewitching her were executed. Goodare says: “There’s fairly clear psychosis of some kind around Christian Shaw.”

Another young girl called Janet Douglas, part of the “Pollock Panic” in Glasgow in the 1670s, showed signs, says Goodare, “of what clinical psychologists today would call catatonic mutism”.

If there was any one condition which possibly affected both the accusers and the accused, then the most likely candidate is sleep paralysis, says Goodare. It can cause hallucinations and out-of-body experiences. Back in the 1600s, it was known as being “hag-ridden” – as if your sleeping body was possessed by a witch. There are examples of accused witches saying the Devil came to them while they were in bed.

Aliens and fairies

THERE is clearly a connection here with the modern phenomenon of people claiming to have been visited by aliens, often in their bedrooms. People may “interpret sleep paralysis in cultural terms”, Goodare suggests. So, someone who today genuinely believes they have been the victim of an “alien abduction” may have 400 years ago believed they were meeting Satan. Yet in both instances the cause was just sleep paralysis.

Similarly, some people when questioned whether they met the Devil, says Goodare, claimed: “Well, I didn’t meet the Devil, but I did meet the Queen of the Fairies.” Goodare says it appears as if these people actually believed they had met fairies. “It takes us back to hallucinations,” he says.

“There’s people today having hallucinations and reporting they got taken into spaceships. I see nobody in the 17th century say ‘I got taken away in a spaceship’ but I do see people say they got taken to fairyland.”

The problem was that if these people who genuinely believed they had met fairies – either because of sleep paralysis or some other condition – made such claims to their interrogators they were still digging their own graves. Meeting fairies rather than demons wasn’t going to help them with witch-hunters who thought, says Goodare, that fairies were just demons in disguise.

Witch-hunting was “largely a lowland phenomenon. It doesn’t get much traction in the Scottish Highlands and very few Gaelic speakers are executed for witchcraft”. There’s a theory that without the widespread belief in fairies across Gaelic-speaking regions, the witch hunts could have been even more ferocious. Significantly, Gaels blamed bad luck on fairies, not neighbours suspected of witchcraft. “That could really cut out hunting before it ever occurred,” says Goodare.

The protestant church, with the Kirk Session and its reforming zeal that spilled over into witch-hunting, also “doesn’t get traction on the ground” in Gaelic areas.

Why women?

ABOUT 85 per cent of victims in Scotland were women – in Europe, the figure was around 80%. There’s a number of reasons why women bore the brunt of persecution.

Firstly, society viewed witchcraft as more likely to be the work of women. If men were going to do wrong it would be through acts of violence, not curses. “The stereotype was that women would use underhand means,” says Goodare.The Margaret Barclay case in Irvine in 1618 is a prime example. Barclay had fallen out with a local sea captain who had slandered her. “She comes down to the quayside in front of everyone and points the finger at him,” says Goodare, calling on God to let “the crabs eat him”. Unfortunately for Barclay, the ship sinks. “That’s all it took for her to be pinpointed as a witch and killed. The panic spread and others were also accused and burned. “These are the sorts of village everyday interactions.”

The bigoted view that women were more likely to be witches is similar, Goodare feels, to events today where ethnic minorities are more likely to be frisked by police.

Crucially, however, women were also inclined to accuse women. Many “village-level quarrels were among women. So this isn’t simply men putting women down. It’s as likely to be a woman who complains saying somebody else bewitched me”.

Uncomfortable though it may be to consider today, most women wanted to “conform to patriarchal norms” in this period. That meant “trying to behave like a good, married woman, nurturing your family, and protecting your family from magical attack – and that means women will perceive other women as witches”. Goodacre adds: “Witchcraft divides women.”

Scottish factor

WHY were the witch hunts so brutal in Scotland compared to elsewhere? In Scotland, the hunts lasted between 1563 and 1736, until the repeal of the Scottish Witchcraft Act. From nearly 4,000 accusations, around 2,500 people were burned in a population of just one million.

However, Goodare says: “My gut feeling is that number is too low and the real figure is likely to be more. In European terms, if you look at the average, Scotland is about five times as high. If Scotland executed the average number you’d expect about 500 dead – I tend to see this in terms of the strength of the reformation here.”

Quite simply, Scotland was much more zealous so therefore more prone to panic and witch-hunting. One need only look to how protestant reformers were unable to “ban” Christmas in England –not so in Scotland, proving the power of the Kirk.

King James was also “a contributory factor”. His book Daemonologie (James coined the term) “attracts attention to the whole phenomenon. He sets things going, gives legitimacy, politicises it, makes it okay for the high levels of government to be interested in these things in a way that perhaps they might not have been otherwise.”

Panic ends

THE witch hunts burned themselves out as the scientific revolution kicked in, showing “new ways of thinking about the physical world”. Come the Enlightenment “the decline is well under way”. Scientists and philosophers like Sir Isaac Newton and René Descartes were central to the erosion of superstition. “They look at stuff and start from the assumption that it’s physical material. That’s cool – that’s new. That’s cutting-edge science.” Once science comes to the fore, society begins to “lose sight of the demons”.

Equally, the law changed too. “Judicial scepticism was crucial,” says Goodare. Judges begin demanding the “highest standards of proof” and become “disapproving of torture”.

As so much of the witch hunts were based on class – with those in charge setting the terms of the debate around witchcraft – the panic only really came to an end as “the beliefs of the elite change”.

Europe had also bled itself white in bloody religious wars in the 1600s and there was a mood “that this has just got to stop”. Goodare equates the change to the post-1945 period when the public believed “we’ve got to just not do that again”.

Legacy

ONCE the witch hunts ended they retreated into myth, legend and entertainment. Historians tended to ignore the terrible violence that had happened, until Goodare’s generation of scholars came along and started researching social and cultural history.

So, the big question remains: how do we remember this part of our past? Goodare supports the idea of pardons and apologies. However, he’s keen on a memorial similar to the one in Norway commemorating victims of the witch hunts.

“A memorial would spark more conversations, more people would see it, talk about it and take lessons away from it – I’d like to see that happening.”

Most importantly, says Goodare, understanding and reflecting on the true history of the witch hunts would be the biggest testament to those who lost their lives.

We need to learn some tough truths, he suggests, including the fact that the witch-hunters themselves didn’t do what they did “because they were evil”. They did what they did because they thought their motives “rational” and on the side of “good”.

“I really want people to think, ‘would I have done any better in their position’? I’d like people to think about our propensity to panic, to lose sight of the principles of justice when we feel strongly about a particular issue, how we pre-judge people and believe we’re right and others are not because we hate them, and if we hate them we can do whatever we like to them. Those things are universal and haven’t gone away.

If that becomes part of the conversation then I’d feel that I haven’t wasted my time.”

Why are you making commenting on The Herald only available to subscribers?

It should have been a safe space for informed debate, somewhere for readers to discuss issues around the biggest stories of the day, but all too often the below the line comments on most websites have become bogged down by off-topic discussions and abuse.

heraldscotland.com is tackling this problem by allowing only subscribers to comment.

We are doing this to improve the experience for our loyal readers and we believe it will reduce the ability of trolls and troublemakers, who occasionally find their way onto our site, to abuse our journalists and readers. We also hope it will help the comments section fulfil its promise as a part of Scotland's conversation with itself.

We are lucky at The Herald. We are read by an informed, educated readership who can add their knowledge and insights to our stories.

That is invaluable.

We are making the subscriber-only change to support our valued readers, who tell us they don't want the site cluttered up with irrelevant comments, untruths and abuse.

In the past, the journalist’s job was to collect and distribute information to the audience. Technology means that readers can shape a discussion. We look forward to hearing from you on heraldscotland.com

Comments & Moderation

Readers’ comments: You are personally liable for the content of any comments you upload to this website, so please act responsibly. We do not pre-moderate or monitor readers’ comments appearing on our websites, but we do post-moderate in response to complaints we receive or otherwise when a potential problem comes to our attention. You can make a complaint by using the ‘report this post’ link . We may then apply our discretion under the user terms to amend or delete comments.

Post moderation is undertaken full-time 9am-6pm on weekdays, and on a part-time basis outwith those hours.

Read the rules hereLast Updated:

Report this comment Cancel