It is only a journey of the mind now. A train full of people, all in their Sunday best. Smiling and happy. Buckets and spades and sandwiches. To the left are the fields of Fife, to the right is the sea, and at times you’re so close to the water it feels like the train is flying over it.

Look at the names of the stations as they go by. Largo. Elie. St Monans. Pittenweem. Stravithie. It’s a train journey that hasn’t been physically possible for 55 years.

Robert Love remembers it well. The retired TV producer, best known for creating Taggart, grew up in Paisley and remembers his entire family decamping to the East Neuk of Fife for summer holidays in the 1940s and 50s.

The Glasgow folk always headed off in July for the Fair Fortnight, but the Paisley holiday was later, at the beginning of August. The first trip Robert took was in the hot summer of 1947 when he was 11 years old.

Like hundreds of other families, they would take the train from Glasgow Queen Street. One of Robert’s strongest memories is the long queues and everyone waiting at the gates then making a mad dash for the trains to get a compartment to themselves.

In that first year, rationing was still in place so Love’s parents sent a trunk full of tinned food up ahead. The atmosphere in the station, he says, was warm and happy. Everybody had the same destination: their holidays.

The train journey itself is also still vivid in Love’s mind. The golden fields. The sparkling Firth of Forth. Love, like lots of other boys in those days, was a gricer, or trainspotter, so he would sit at the window and spend his time noting down the numbers of other trains as they passed.

And he remembers how warm it was. “The weather seemed totally different,” he recalls. “All I remember from my holidays in Glasgow is rain, but that first year in Fife it was cloudless blue skies.”

Coastal line

THE final destination for Love and his family was always the same: a fisherman’s cottage in the village of Pittenweem, the eighth stop on the coastal line that went all the way to St Andrews.

“We loved that journey along the coast,” says Love. “The single line with passing loops at the stations, golden beaches, green golf links, the viaduct at Lower Largo harbour, which is still standing, and the occasional ruined watchtower.”

Some 70 years on, Love’s nostalgia for the trip is still strong but it’s more than nostalgia now. In fact, an interesting possibility has opened up with the news that construction work has started on reopening a six-mile stretch of the coastal line from Thornton to Leven. Due to be completed in 2024, it means that in a couple of years, Love will be able to make at least part of a journey that he hasn’t done for more than half a century.

And it’s not the only sign of change on a network that was so famously decimated by the Beeching cuts in the 1960s. The Borders line from Edinburgh to Tweedbank has been reopened now for seven years but in the next few days, Reston station, on the East Coast Main Line, will also reopen to passengers for the first time since Beeching, reconnecting the village to the train line for the first time since the 1960s.

The hope is that it is only the beginning. Railfuture Scotland, the independent group that represents passengers, has prepared a study on all the stations and lines that could be reopened.

It reports that 50 stations could realistically be added to the network and top of its list is Glasgow Cross on the Trongate, which was shut in 1964. Also on the list is the circle line in Edinburgh with stops at Gorgie and Morningside, and new stops on the Ayrshire line to Dumfries. Also mooted is an extension of the Borders line down to Carlisle.

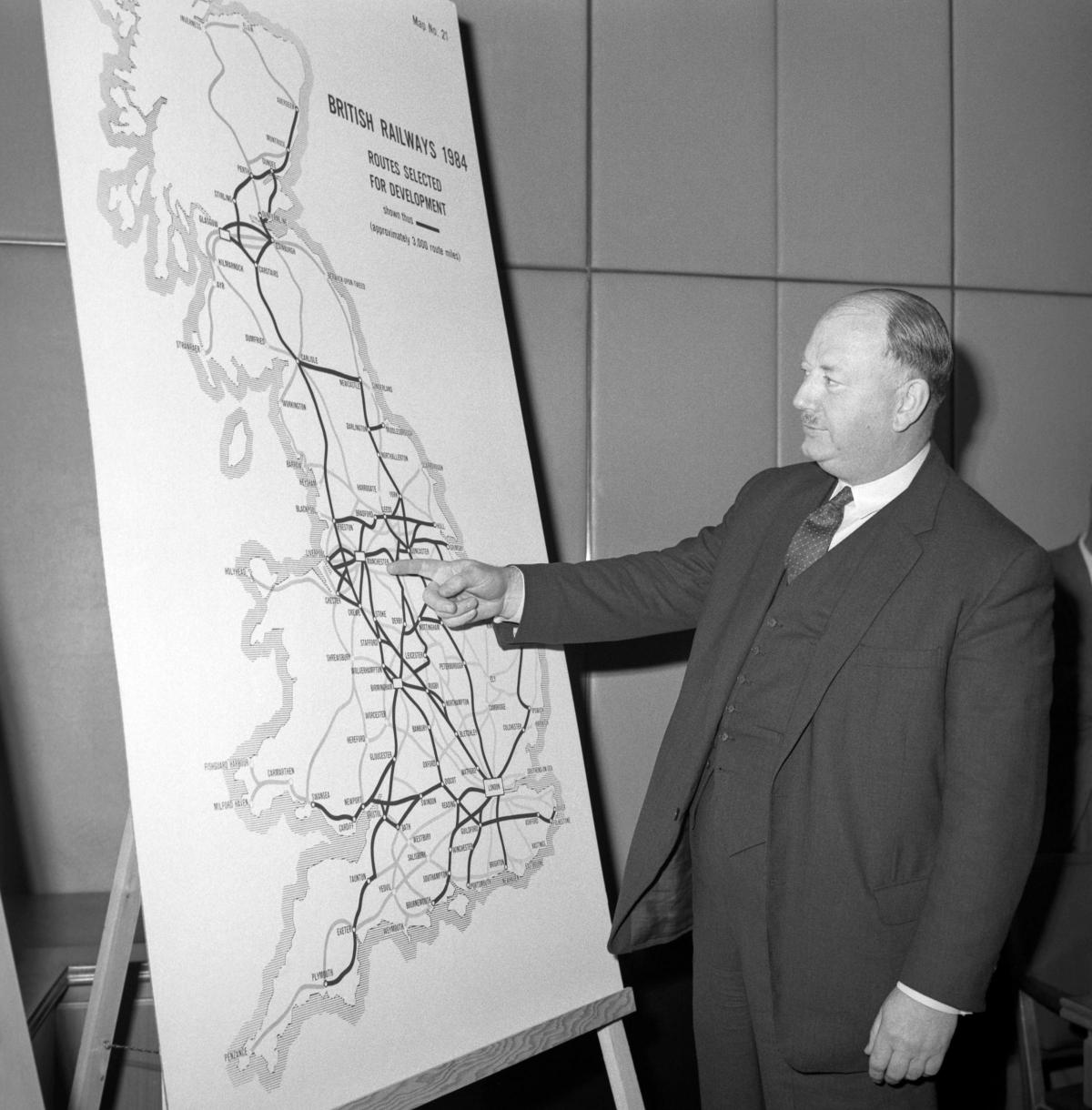

Even if only some of these plans come to fruition, it would be a significant reversal of the cuts which happened in the 1960s, although Beeching’s original plans were actually much more drastic. Under his initial proposals, Scotland would have been left with no passenger services north or west of Inverness, northeast of Aberdeen, south of Ayr, or through the Borders from Edinburgh. There was even concern at one point that all trains north of Perth might be axed.

Not profitable

THE official explanation for the cuts at the time was that much of the network was no longer profitable, but they were deeply controversial from the word go. When Richard Beeching visited Scotland in 1962, ahead of the publication of his report, he was met with demonstrators wherever he went.

At Waverley, the crowd surged forward and one man aimed a kick at him. The SNP also sent a telegram to Michael Noble, Secretary of State for Scotland, protesting that Scotland was getting twice its share of the cuts. If he did not stop the closures, they said, he would prove that Government pledges to Scotland were worthless.

The cuts were controversial – and still are. But were they necessary? Reporting on the proposals on March 28, 1963, The Herald said in its leader article that the Beeching report was generally defensible and should be accepted in its outline, and that the operation of the railways, which had a deficit of £136 million, had to be rationalised.

It also said the disappearance of more than 2,000 stations and halts, and a number of lines, was necessary if large-scale operations based on intercity operations were to be given a chance.

However, The Herald also had a warning. Some of the areas affected, it said, had a good claim to be retained in the reshaped railway. It also pointed to American cities which had allowed urban train services to be abandoned as “inessential” and were now beset with problems and traffic jams. If the plans went ahead, warned The Herald, British cities might have to reckon with traffic problems on the present American scale. Anyone who has ever been stuck on the M8 would probably say that the warning came true.

Tim Dunn, the railway historian and TV presenter, agrees that some kind of rationalisation or reduction in the network was probably necessary and points out that cuts had been introduced in the UK long before Beeching.

“What we were seeing then,” he says, “was a general trend because people were changing their habits at a time when the use of the car was on the increase. The other issue is that there was a serious over-supply of railway line in many parts of the country.

“You have the Great Central Railway, for example, which ran from London Marylebone all the way through Aylesbury up to Nottingham, Sheffield and Manchester – it was often called the last great main line. It was built at the turn of the century but it was seriously underused because the traffic didn’t materialise.

“And even as far back as 1835, you have the Southern Railway shutting down various branch lines.”

Dunn can also see what the problem was with the Fife coastal line that Robert Love and his family enjoyed so much. “At what time was that being used?” he asks. “An infrastructure to be used by a few thousand people in a short burst during the holidays – is it worth keeping the line open for that?”

He also believes that Beeching himself has been rather unfairly maligned.

“People often criticise Beeching,” he says, “but I often say that he’s unfairly made out to be the evil genius. He was basically carrying out orders under the transport minister Ernest Marples, the man who had shares in a big road-building company as did his wife. There was less scrutiny back then.”

‘Superfluous’

DUNN also points out the bigger context for the Beeching cuts. “It came at a time when we didn’t place much on the social value of public transport,” he says, “and that’s the major part that was missing from the calculations. In all the surveys that were done around the time of the Beeching cuts, they were being done with the best information that was available to them at the time which was saying these railways are superfluous.”

However, that said, Dunn believes that when the Beeching axe did eventually fall, Scotland was particularly badly hit.

“Scotland was completely wrecked by the Beeching cuts compared to the southeast of England,” he says, “and that was because in the southeast a lot of the lines were commuter routes and therefore were profitable whereas in the west Highlands, out to the coast, they were unprofitable.

“The Killin branch in the Highlands, for example, was a locomotive and one carriage but that required a driver, fireman and guard, and every station had to have its station master and porter and so on.

“It was extremely expensive to run that kind of infrastructure. Today, you might run it with a rail bus perhaps or a reduced light railway – we have better ways of dealing with these situations.”

Dunn’s point that some parts of the country were more affected than others by the Beeching cuts also leads him to another important point. If the cuts are to be reversed, he says, there may be a stronger case in some areas of the country than others for restored lines and stations.

“We look back on some of these lines with a slightly rose-tinted view and think gosh, wouldn’t it be lovely to have these back. But they weren’t well used back then – do we need them now?” he says. “The answer is yes, we probably could do with a lot of them back but not all of them.

“There are places where the case can be made to bring them back, such as Reston, for example, where actually the community has grown sufficiently and we’ve got to a point in our society where we’ve recognised that connectivity with two strips of steel that connects us to the next town is very important. That may be because we believe in democratic transit and by that I mean not everyone can afford to have a car - not now anyway, when the cost of fuel is rising and rising.

“Also, we’re looking at a future where green transit is much more important. A road requires you to have a private car or a bus and the thing about buses is that there was supposed to be a network of buses to replace the Beeching cuts.

“But, of course, bus deregulation means those buses didn’t necessarily materialise so some communities were cut off and that was never supposed to be the plan – they were supposed to be kept together by buses but they have disappeared after years of cuts and changes in legislation.”

Two strips of steel

THE other problem, says Dunn, is that buses and cars can never provide quite the same feeling as what he often refers to, rather lovingly, as two strips of steel.

“In urban areas,” he adds, “people prefer to have trams to buses and the reason for that is if you have these two strips of steel so it’s seen as a more secure and predictable route, because buses can be taken away just like that.

“If you think about those two strips of steel, back in the 1840s we had railway mania – one company would connect to the next town, then another company would connect to the next town, and you’d end up with a net and this net effectively binds a region or an area or a county or a country.

“Once you sever that strip of steel, that town effectively floats loose because it’s no longer on the timetable, you can’t catch a train from there, you can’t catch a train to Paris or London. The net has been cut open.”

Dunn says that, by contrast, buses and cars are more transient. “And there is a psychological element to the strips of steel,” he says. “They’re steel, they’re there on the ground, they’re visible. A bus might come along at a certain time but a railway has signals, it’s got a timetable, it’s got platforms, it’s visible, tangible infrastructure, and that’s why trams and trains are also preferred by most people to buses.

“You see these strips of steel and you think there will be a train along in a moment or two. A bus could be any time at all and can deviate from its route.”

‘Superfluous’

ROBERT Love certainly feels this way. The Fife coastal line that he and his family used for many years was eventually closed in 1966, and Robert’s parents had to use the bus to get up to Pittenweem.

It meant the trip was never quite the same but, like Dunn, Love is realistic about what had to be done at the time. “There probably had to be some rationalisation,” he says. “There were too many branch lines which just weren’t profitable and in some respects Beeching did some quite good things like introducing the idea of intercity trains.”

However, Love is also pretty excited about the prospect of the Fife line opening up again and Tim Dunn believes that the trend might accelerate, partly because the industry is looking at ways of reducing how much it costs to reopen old stations and lines.

It is still a pretty expensive business, of course, because lines and infrastructure built in the 1800s and left to rot are no longer fit for purpose. But Dunn believes there can be ways to use what’s there to keep the costs down.

He is also pretty excited by the prospect of Reston station reopening next month.

It will put more people in easier touch with Edinburgh, he says, and down south and then on to the continent – and that can only be a good thing.

Robert Love is also looking forward to the prospect of the line to Leven opening again in the future, meaning that he could take the train trip again for the first time since he was a boy.

Will he be doing the journey when the line reopens? “I shall,” he says, “I shall.”

Tim Dunn presents Secrets of the London Underground on the Yesterday channel on Thursday, May 5.

Why are you making commenting on The Herald only available to subscribers?

It should have been a safe space for informed debate, somewhere for readers to discuss issues around the biggest stories of the day, but all too often the below the line comments on most websites have become bogged down by off-topic discussions and abuse.

heraldscotland.com is tackling this problem by allowing only subscribers to comment.

We are doing this to improve the experience for our loyal readers and we believe it will reduce the ability of trolls and troublemakers, who occasionally find their way onto our site, to abuse our journalists and readers. We also hope it will help the comments section fulfil its promise as a part of Scotland's conversation with itself.

We are lucky at The Herald. We are read by an informed, educated readership who can add their knowledge and insights to our stories.

That is invaluable.

We are making the subscriber-only change to support our valued readers, who tell us they don't want the site cluttered up with irrelevant comments, untruths and abuse.

In the past, the journalist’s job was to collect and distribute information to the audience. Technology means that readers can shape a discussion. We look forward to hearing from you on heraldscotland.com

Comments & Moderation

Readers’ comments: You are personally liable for the content of any comments you upload to this website, so please act responsibly. We do not pre-moderate or monitor readers’ comments appearing on our websites, but we do post-moderate in response to complaints we receive or otherwise when a potential problem comes to our attention. You can make a complaint by using the ‘report this post’ link . We may then apply our discretion under the user terms to amend or delete comments.

Post moderation is undertaken full-time 9am-6pm on weekdays, and on a part-time basis outwith those hours.

Read the rules hereLast Updated:

Report this comment Cancel