SEVERAL decades ago, a young Scottish journalist was on the phone to a senior editor at Associated Press of America, relaying information about the high-profile campaign against the South Uist rocket-range. The editor made a note of the facts then paused and asked: “Okay, now where the hell is Wendy Wood fitting into all this?”

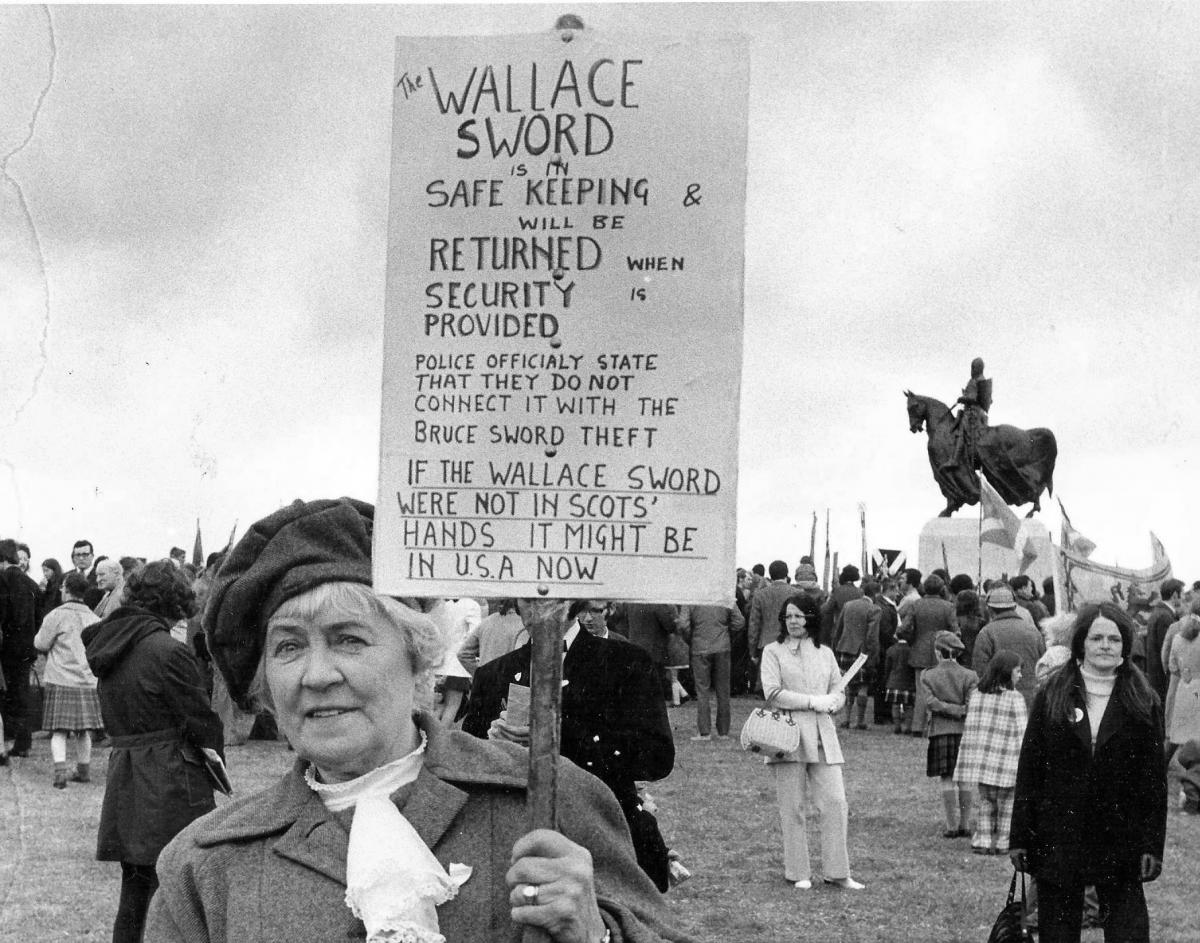

It was an understandable question. Wood, who died in 1981, aged 88, was a prominent Scottish patriot with a flair for campaigning and drawing attention to many causes. Her fame, as the journalist, Hugh Cochrane, would observe, had spread as far as America. If there was a fiery cross, he said, she wasn’t usually far away: “She was mixed up with nearly every Scottish protest that came along, even getting guilt or praise by association when she was not involved”.

Wood had a long and colourful history, from contesting the Glasgow Bridgeton by-election in 1946 after the death of James Maxton (her campaigning props memorably included a large pat of butter) to tearing down the Union Jack from Stirling Castle in 1932.

Throughout her life she campaigned relentlessly for independence, and established numerous groups, including the Scottish Patriots; she made a nuisance of herself and served time in prison; 50 years ago, aged 80, she embarked on a “fast unto death” in an effort to persuade the Conservative government to honour its election promise to publish a Green Paper on plans for a Scottish Assembly.

A talented painter (in her youth she had been one of artist Walter Sickert’s most promising pupils), she continued to paint every day, even when in her 80s. She marked her 88th birthday by supervising an exhibition of her work at the city’s Saltire Gallery. Late in life she had also become a popular storyteller on television.

She was still a figure of some intrigue, as least as far as newspapers were concerned. You couldn’t blame her for writing to the Glasgow Herald editor in 1979, saying that the paper might like to check the facts of her life in readiness for her obituary. “I am not ill or expecting to go yet,” she wrote, “but you never know!”

Wood was born in Kent and spent most of her early life there and in South Africa, where she was educated. In Cochrane’s words, she “took up Scotland the way that Isadora Duncan took up dancing. Through her Scottish ancestry, she believed that she had second sight and that she was a natural leader. With her gift for hyperbole and for garbled, music-hall Lallans, she also exhibited passions that would not be bridled by historical accuracy”.

As she approached middle age, Cochrane added, writing in 1981, Wood was one of a number of “forceful nationalists” – people such as Dr John MacCormick, RE Muirhead, Robert Cunninghame Graham and Oliver Brown – “who helped to give Scottish political life a vivacity and, occasionally, a jolt of impulsive ideas, to a large extent lacking nowadays”.

Wood’s passion for Home Rule began in the early 1920s when she toured the Highlands with her then husband and was dispirited by the sight of so many crofts in ruins. “I knew then,” she said, many years later, “that something was terribly wrong and I felt great bitterness that so much should go by without any recognition.” Rather than “dwindling into housewifery” she decided to become a full-time patriot.

She made the headlines in June 1932 when, addressing a rally in Kings Park, Stirling that marked the anniversary of Bannockburn, she said that the Union Jack was flying from the ramparts of Stirling Castle. “Are we going to allow that flag to fly there on such a day? Who will volunteer to take it down?” She and 100 other young men and women marched on the castle, hauled down the Union flag and replaced it with the Scottish standard.

In August 1946, while standing as an independent Scottish Nationalist candidate in the Bridgeton by-election, she caused a stir by bringing to one meeting a 4lb block of fresh butter, which came from the Highland croft that she ran with her husband. Her point was that the Home Rule she was advocating would bring practical and speedy benefits, such as plenty of Scots butter in Scots larders. The butter was distributed to her friends and supporters (although someone had stolen an amount of Highland peat that she had sent to Bridgeton as further proof of Scotland’s wealth). On polling day she attracted a commendable 2,575 votes, and kept her deposit.

She was rarely far from the news, whether it was through her brushes with the law (she once endured the conditions in Glasgow’s Duke Street prison after refusing to pay a £15 fine for not keeping up her National Health Insurance contributions), or establishing the Scottish Patriots.

In April 1951 she was arrested in London, charged with obstructing the police in an incident in Trafalgar Square, where she addressed a crowd about the ancient Coronation Stone at Westminster Abbey (four Scottish students had removed it from there on Christmas Day 1950). Found guilty at court, she chose to go to jail rather than pay a fine; she served several days in Holloway Prison but was freed after a well-wisher paid the fines.

Incidentally, former Glasgow Herald editor Arnold Kemp says, in his book, The Hollow Drum, that the idea of liberating the Stone had originally been made by Roland Muirhead in a letter to Wood in 1937, but that Ian Hamilton QC, one of the four students involved, had been unaware of such a provenance. In his own book, A Touch of Treason, Hamilton wrote that, as a boy, he had seen a Bulletin photograph of Wood on Edinburgh’s Royal Mile, bearing a placard with the words: “England disgorges some of the loot, but where is the Stone of Destiny?” The picture, and his mother’s account of the Stone’s history, created an abiding interest in him in the Stone.

In December 1972 Wood announced her “fast unto death”. Scots Secretary Gordon Campbell told the Commons that the plan had always been to publish a Green Paper on a Scottish Assembly in due course after Parliament had passed a Bill reforming local government. Her gesture, he said, was “not very sensible”.

On December 12, the government said it would publish a Green Paper, on alternative proposals for an Assembly, and Wood ended her week-long fast after Labour MP Jim Sillars made a personal appeal to her on Scottish Television. In her 138-hour fast she had sustained herself only with water. Michael Hirst, national vice-chairman of the Scottish Young Conservatives, lamented that the government had yielded to Wood’s “publicity-seeking stunts”.

Interviewed by the Herald at her Edinburgh home in late February 1979, Wood said what she remembered most clearly about herself was not her audacity but her shyness. “I was a very silent child. For a long time I thought I was adopted because I seemed a little different from the rest of the family. But I’ve always been possessed by this Scottish drive to get things done. I’ve hated the publicity but nothing in the world has ever been gained without fanaticism.”

The Assembly referendum was days away. Wood believed the assembly would “enrich our lives” and provide a stepping-stone to the “absolute certainty”of complete independence. But she was to be grievously disappointed on March 1: though 51.6% voted Yes and 48.4% No, the Yes side failed to meet the requirement that 40% of the total electorate vote in favour, and the devolution dream faded for many years.

Why are you making commenting on The Herald only available to subscribers?

It should have been a safe space for informed debate, somewhere for readers to discuss issues around the biggest stories of the day, but all too often the below the line comments on most websites have become bogged down by off-topic discussions and abuse.

heraldscotland.com is tackling this problem by allowing only subscribers to comment.

We are doing this to improve the experience for our loyal readers and we believe it will reduce the ability of trolls and troublemakers, who occasionally find their way onto our site, to abuse our journalists and readers. We also hope it will help the comments section fulfil its promise as a part of Scotland's conversation with itself.

We are lucky at The Herald. We are read by an informed, educated readership who can add their knowledge and insights to our stories.

That is invaluable.

We are making the subscriber-only change to support our valued readers, who tell us they don't want the site cluttered up with irrelevant comments, untruths and abuse.

In the past, the journalist’s job was to collect and distribute information to the audience. Technology means that readers can shape a discussion. We look forward to hearing from you on heraldscotland.com

Comments & Moderation

Readers’ comments: You are personally liable for the content of any comments you upload to this website, so please act responsibly. We do not pre-moderate or monitor readers’ comments appearing on our websites, but we do post-moderate in response to complaints we receive or otherwise when a potential problem comes to our attention. You can make a complaint by using the ‘report this post’ link . We may then apply our discretion under the user terms to amend or delete comments.

Post moderation is undertaken full-time 9am-6pm on weekdays, and on a part-time basis outwith those hours.

Read the rules hereLast Updated:

Report this comment Cancel