I know my mindset isn’t for everyone facing obstacles in life. But I always see my tumour in a sporting context. It is like being 6-0 down, can I come back and win this?

So I felt a rush of energy through my body when I saw Liverpool then Tottenham recover from three-goal deficits in back-to-back nights to book their Champions League final spots this week.

You might just say they are just games of football. But they were something much greater to me.

Watching these players fight for something as a team which is far greater than them as individuals was something very inspiring for me. Mo Salah’s T-shirt, with the words “never give up”, says it all.

Every recovery has to start somewhere and this week has been a fairly big for me. Because, with both mind and body hitting rock bottom, I made a decision that I was starting my rehabilitation. Sport is all about small steps – you might just see one hundredth of a second’s worth of improvement for six months’ work. But I have written the word perseverance on my wall as a reminder never to give up.

As I lay in bed the other day looking at my bike the conversation in my mind went a bit like this. “Let’s get on the bike”. “No, we’d better not as the body is still recovering, and the doctor said three months for the body to recover”. “But I can’t sit for another three months - I will go mad”. I came to the conclusion that it is all about how much I want it. Am I willing to suffer today to be better tomorrow?

Every time someone has asked me how I am recently, my go to response has been to say ‘I feel dreadful’. It is true, I DO feel dreadful but for me to turn a corner, I have to start telling both myself and others that I feel great. I need to take control of my thoughts and reel the voice in my mind in. It would be easy to give up now, I could think of so many reasons to say that’s it, but as Thomas Edison said, to succeed you just have to keep trying one more time.

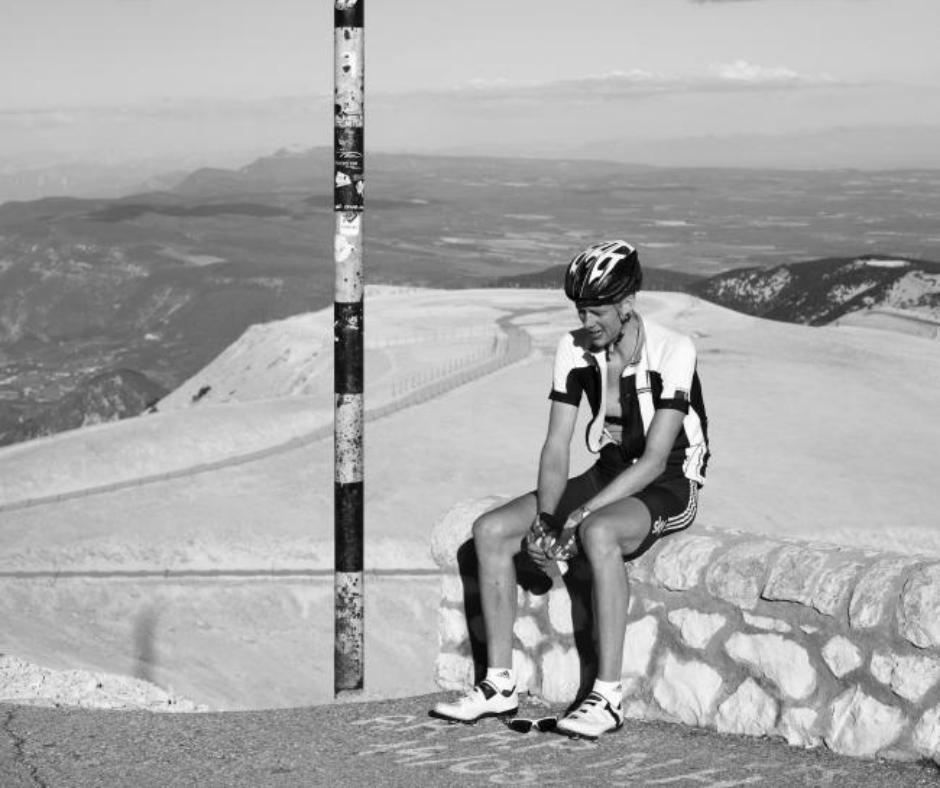

So on the Anniversary of the 2015 Mont Ventoux cycle which I completed just six months after my third surgery, I pulled on my cycling shoes again and climbed back onto the bike.

This really was starting again from ground zero. This was so much harder than anything I did post-surgery, as my cells fight to recover from the zapping. The pain just turning the pedals is unlike anything I have experienced, just the effort involved in turning them sends my heart rate to 140 bpm.

How do you control the mind during this? Its back to those small steps and telling myself I am not giving up. I thought back to that day on Ventoux to find strength. Knowing I had got through this then, I can do it again.

Ventoux, which claimed the life of British cyclist Tommy Simpson in 1967, has been described as the mountain of hell. An arduous 6,273-foot colossus, there is no vegetation surrounding the upper reaches of the climb, just bare limestone. Roland Barthes, French philosopher and bicycle racing fan, calls it a “god of Evil, to which sacrifices must be made”. “Once you leave the forest of hell, it’s time to enter a sea of suffering,” he added. It is much like another two surgeries and radiation has felt for me.

The doctors thought I was mad to even contemplate climbing it. This was just six months after I remember lying in my hospital bed in October 2014, unable to even sit up.

But I believed I could. I lay there looking out the window holding back tears but telling myself I will stand on the top of Mont Ventoux in six months’ time, and true enough that dream came true. In fact, I wasn’t content with cycling up it once. I wanted to conquer it completely, doing it three times on three separate routes in one day.

Perhaps that explains how much I am craving the suffering of being on my bike again. I want to feel like an athlete again, know the feeling of pushing my body and mind and leaving the last five months behind me.

University College London believe it takes 66 days to build a habit, so it is safe to say I have built some bad ones since surgery in November. Sleeping most of the day, eating tubs of ice cream and watching hours of Netflix is not the existence I want to have. Even as my body recovers, I’ve found my mind has a habit of slipping into a low place.

All these bad habits feel good. They light up the part of the brain where dopamine is released, the pleasure centre of our brains. So each time I eat a tub of ice cream I get this reward in my mind which is known as the opioid loop.

But we can all change our bad habits. So as I climbed off the bike, feeling worse than ever, I did what I know best, and went to the gym for an hour. I recalled something Dr Steve Peters said to me away back before my last surgery about using positive language around training. So I was lucky. I got to go to the gym.

Why are you making commenting on The Herald only available to subscribers?

It should have been a safe space for informed debate, somewhere for readers to discuss issues around the biggest stories of the day, but all too often the below the line comments on most websites have become bogged down by off-topic discussions and abuse.

heraldscotland.com is tackling this problem by allowing only subscribers to comment.

We are doing this to improve the experience for our loyal readers and we believe it will reduce the ability of trolls and troublemakers, who occasionally find their way onto our site, to abuse our journalists and readers. We also hope it will help the comments section fulfil its promise as a part of Scotland's conversation with itself.

We are lucky at The Herald. We are read by an informed, educated readership who can add their knowledge and insights to our stories.

That is invaluable.

We are making the subscriber-only change to support our valued readers, who tell us they don't want the site cluttered up with irrelevant comments, untruths and abuse.

In the past, the journalist’s job was to collect and distribute information to the audience. Technology means that readers can shape a discussion. We look forward to hearing from you on heraldscotland.com

Comments & Moderation

Readers’ comments: You are personally liable for the content of any comments you upload to this website, so please act responsibly. We do not pre-moderate or monitor readers’ comments appearing on our websites, but we do post-moderate in response to complaints we receive or otherwise when a potential problem comes to our attention. You can make a complaint by using the ‘report this post’ link . We may then apply our discretion under the user terms to amend or delete comments.

Post moderation is undertaken full-time 9am-6pm on weekdays, and on a part-time basis outwith those hours.

Read the rules here