Bucharest’s main concert hall is the Sala Palatului: a vast 1960s period piece upholstered in multiple shades of yellow and once used as the conference centre for Nicolae Ceausescu’s communist regime. The auditorium holds a mighty crowd of 3,000 — in Ceausescu’s heyday it was 5,500 or more — and it was packed to the gunnels last week for Simon Rattle and the Berlin Philharmonic. I found myself sitting crosslegged on a bank of mustard-yellow steps, listening to Sir Simon delve into the dark, stoical, sardonic and transcendent episodes of Shostakovich’s Fourth Symphony. A mother and toddler were wedged by my feet; to my side was an elderly gentleman with his eyes closed, discreetly conducting along to every bar. Music about the terrors of communist authority played in a hall made epic by Ceausescu: the associations felt as loud as any note.

This was the first time the Berlin Phil had ever appeared at Bucharest’s Enescu Festival, a biennial event in the Romanian capital whose programme is eye-poppingly impressive. Visitors this year include the Berlin and Vienna Philharmonics, the Dresden Staatskapelle, the Royal Concertgebouw and the Bayerische Staatsorchester; conductors Mehta, Rattle, Thielemann, Nelsons; soloists Murray Perahia, Elisabeth Leonskaja, Christian Tetzlaff, Andras Schiff, Piotr Anderszewski — I could go on and on. This year also saw the first-ever inclusion of a Scottish group at the Enescu Festival: the Scottish Ensemble, whose concert with Moldovan violinist Patricia Kopachinskaja was spirited, eloquent and original. More on that in a moment.

First, the matter of how Europe’s second poorest country can host a concert series to rival the super-suave summer festivals of Austria or Switzerland. Of the Enescu’s budget, 70 per cent — roughly 6 million euros — is financed by the Romanian government, the rest from ticket sales and sponsors. There’s vested interest here. The Enescu Festival was founded in 1951 “for political reasons, of course” says the current director Mihai Constantinescu. He’s a straight-talking man who has worked for the festival since 1991 and has an encyclopaedic knowledge of every past programme. We’re talking in his tiny, cramped office in the north of the city; if there’s money behind the Enescu Festival, it appears to be spent on visiting artists, not administration.

“The festival started in an era when the communist bloc was fighting against capitalism,” he explains matter-of-factly. “Romania wanted to prove how strong our culture was here.” Ceausescu would later seize the event as a chance for nationalist myth making, introducing a strand called Singing for Romania and ordering that only eastern-bloc artists should be invited. The festival survived the country’s 1989 revolution and subsequently opened its doors as wide as it could.

Today’s Romanian government funds the Enescu Festival partly to bolster the country’s international image, with around 20,000 foreign visitors attending each year. But to me the experience felt overwhelmingly rooted at home. The concerts I attended were full of local music students and members of Romanian orchestras, who are given tickets for free, as well as Bucharest’s well-heeled elite. “It’s important for Romania, it’s important for culture, it’s important for our sense of who we are,” says Constantinescu. “People here don’t have the money to buy tickets to hear this level of artist so the government subsidises.”

The name, incidentally, is more than emblematic. Cold War point scoring was one incentive, but the festival was also founded by the Romanian composers union in honour of George Enescu, Romania’s great violinist and composer and the figure whose face hangs on huge posters around the city. Every visiting orchestra and recitalist is asked to include a piece by Enescu in their programme — a neat idea, as it means Romanians get to hear their own composer played in the different accents of international musicians. I wonder what the equivalent would be: if every author who came to the Edinburgh International Book Festival recited a piece of Burns?

When the Scottish Ensemble played Enescu — his Intermezzi for strings Opus 12 — it was with suppleness and careful attention to detail. The following day, Constantinescu told me he was impressed. “In my opinion the best understanding of Enescu comes from the British orchestras. Because they are strict! They understand how to follow instructions precisely!” And that’s a crucial discipline for a composer whose scores, though deeply rooted in Romanian folk music and laced with the sensuous French impressionism of his adopted country, are fastidiously detailed in technical instructions.

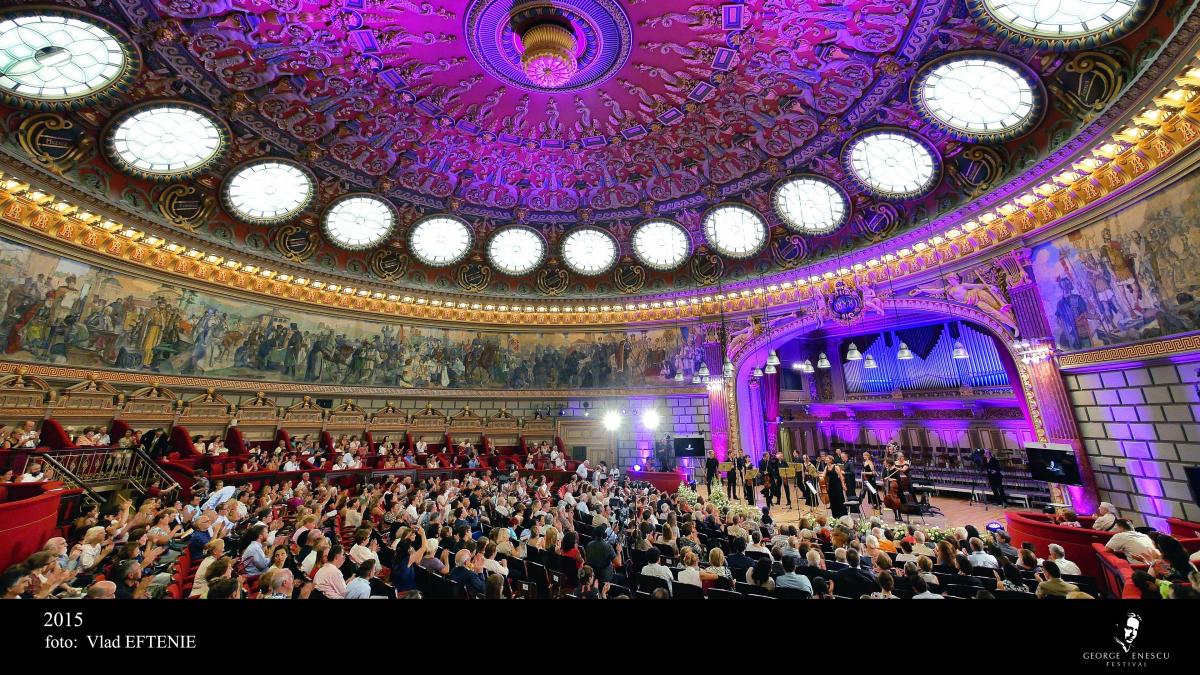

The Scottish Ensemble were performing up the road from Sala Palatului at The Romanian Athenaeum, an ornate 19th century circular hall bedecked with banks of white roses across the front of the stage. They closed their programme with Rudolph Bar?ai’s string ensemble arrangement of Ravel’s String Quartet, full of alert, shimmering colours. Patricia Kopachinskaja joined them for Mansurian’s Four Serious Songs and three of Brahms’s Choral Preludes Opus 122. She appeared from the back of the stage while the ensemble was still tuning, barefoot (she always performs barefoot) and improvising a low arabesque around the ensemble’s tuning note. The Brahms involved singing the chorales as well as playing them, with Kopachinskaja and the ensemble members weaving simple, quiet voices among the dark string textures. In such intimate and noble music, composed shortly after the death of Clara Schumann at the very end of Brahms’s life, it was a moving touch.

Playing at a festival like the Enescu means a lot for the Scottish Ensemble. “The international recognition strengthens our reputation at home,” says Fraser Anderson, the group’s general manager. “We create connections with tremendous artists like Patricia. It’s crucial for the professional development of our players to experience different audiences, different halls, different cultural contexts.”

Then there is the Brand Scotland thing. This is a festival of traditional prestige: big names, old-world glamour, fairly conservative programming. It did not go unnoticed that the first group from Scotland to ever play here was a self-directed string ensemble singing chorales while playing with a feisty barefoot soloist. Responses to the concert — I spoke to a Romanian conductor, a Romanian politics student living in the States and home for the holidays, a visiting German journalist — all noted the group’s freshness, flexibility and ultra-engaged playing. Kopatchinskaja herself seemed excited: “did you hear those colours in the Ravel?” she demanded when I met her the following day. “And the open-heartedness way they sang?” She couldn’t promise when exactly, but she was adamant the collaboration would happen again. Watch this space.

Why are you making commenting on The Herald only available to subscribers?

It should have been a safe space for informed debate, somewhere for readers to discuss issues around the biggest stories of the day, but all too often the below the line comments on most websites have become bogged down by off-topic discussions and abuse.

heraldscotland.com is tackling this problem by allowing only subscribers to comment.

We are doing this to improve the experience for our loyal readers and we believe it will reduce the ability of trolls and troublemakers, who occasionally find their way onto our site, to abuse our journalists and readers. We also hope it will help the comments section fulfil its promise as a part of Scotland's conversation with itself.

We are lucky at The Herald. We are read by an informed, educated readership who can add their knowledge and insights to our stories.

That is invaluable.

We are making the subscriber-only change to support our valued readers, who tell us they don't want the site cluttered up with irrelevant comments, untruths and abuse.

In the past, the journalist’s job was to collect and distribute information to the audience. Technology means that readers can shape a discussion. We look forward to hearing from you on heraldscotland.com

Comments & Moderation

Readers’ comments: You are personally liable for the content of any comments you upload to this website, so please act responsibly. We do not pre-moderate or monitor readers’ comments appearing on our websites, but we do post-moderate in response to complaints we receive or otherwise when a potential problem comes to our attention. You can make a complaint by using the ‘report this post’ link . We may then apply our discretion under the user terms to amend or delete comments.

Post moderation is undertaken full-time 9am-6pm on weekdays, and on a part-time basis outwith those hours.

Read the rules hereLast Updated:

Report this comment Cancel