All My Good Countrymen (12)

Second Run, £12.99

In the brutal clampdown which followed the Prague Spring in 1968, the Soviet-backed authorities in Czechoslovakia took a dim view of many of the films which make up what's known as the Czech New Wave. So much so that in 1973 a list of 100 blacklisted films was produced, most made during this fecund period in the 1960s. But only four out of the 100 received the ultimate sanction and were banned “forever”. This is one of them, Vojtech Jasny's state-of-the-nation film which begins in May 1945 and follows the lives of a handful of Czech villagers over the following decade or so as they are (variously) shot, forced to hand over their farms for collectivisation, accused of political misdemeanours, imprisoned or promoted through the self-serving and corrupt Communist Party hierarchies. It's not hard to see why the authorities thought it so dangerous: it's gloriously and defiantly off-message.

Tempering the bleakness, however, is an almost carnivalesque atmosphere and a colourful cast of characters. There are regular, extended pub scenes featuring music and song and the opening sequence has a couple of boys finding a cache of abandoned arms, picking up an automatic pistol each and taking pot shots at the locals – one of whom is joy-riding in a stolen military vehicle. German, presumably.

As the seasons turn and the years roll over, Jasny's camera dwells lovingly on the landscape. Far less loving is his treatment of those among the townspeople who turn mean, grasping and duplicitous as the solidarity of the immediate post-war period turns to ashes. Extras include his 1969 short film Bohemian Rhapsody, which was also banned.

All My Good Countrymen won Vojtech Jasny the Best Director award at the 1969 Cannes Film Festival, though by that time the director had chosen exile, first in Germany then New York. It would be over 20 years before he made another film in his homeland, but All My Good Countrymen has been an acknowledged influence on both Edgar Reitz's 32-episode TV series Heimat, and Michael Haneke's Palme d'Or-winning 2009 film The White Ribbon.

Kiju Yoshida: Love + Anarchism (18)

Arrow Academy, £59

While the Czech New Wave was ebbing away, its Japanese equivalent was at arguably its highest point, a fact which finds expression in this trilogy of films from director Kiju Yoshida.

The best known of the three is the first film, the epic, three and a half hour Eros + Massacre. Released in 1969 it's essentially a biopic of Sakae Osugi, a socialist, anarchist and proponent of free love who was murdered by the military police in 1923 along with his lover, Noe Ito, a noted journalist. She's played in the film by Yoshida's own wife, Mariko Okada. The other two women in Osugi's ménage à quatre are his wife and his second lover, feminist Masaoka Itsuko, who once tried to stab him to death.

The Osugi story is told in flashback while in episodes set in the present day we see Ito's daughter (also played by Okada) being interviewed about her mother by a young female journalist, Eiko. Eiko has a boyfriend, Wada, as well as series of other sexual partners.

Perhaps the film's greatest triumph, however, is its visual style. Yoshida switches between languid sections which are almost bleached out, and stark black and white compositions in which his actors play at the very edges of the frame. Switching between a modern-day urban Japan which is all stylish apartments, polo necks, airports and sunglasses, and the rural, kimono-clad life of 50 years earlier, only adds to the richness. In some scenes he even brings the two time periods together, for instance when he has a Japanese rugby team play against a group of kimono-wearing men, with a bag containing Osugi's bones taking the place of the ball. It isn't just Eros + Massacre's extreme length which makes it an unforgettable watch.

Also included are Heroic Purgatory and Coup d'Etat. The first was released in 1970 and is probably one of the most puzzling films you'll ever see. Beautifully shot, it uses its avant-garde format as a comment on the topsy-turvy radicalism of the 1960s. Coup D'Etat, from 1973, is a more straight-forward re-telling of a failed 1936 coup attempt by a modernising cadre within the Japanese army.

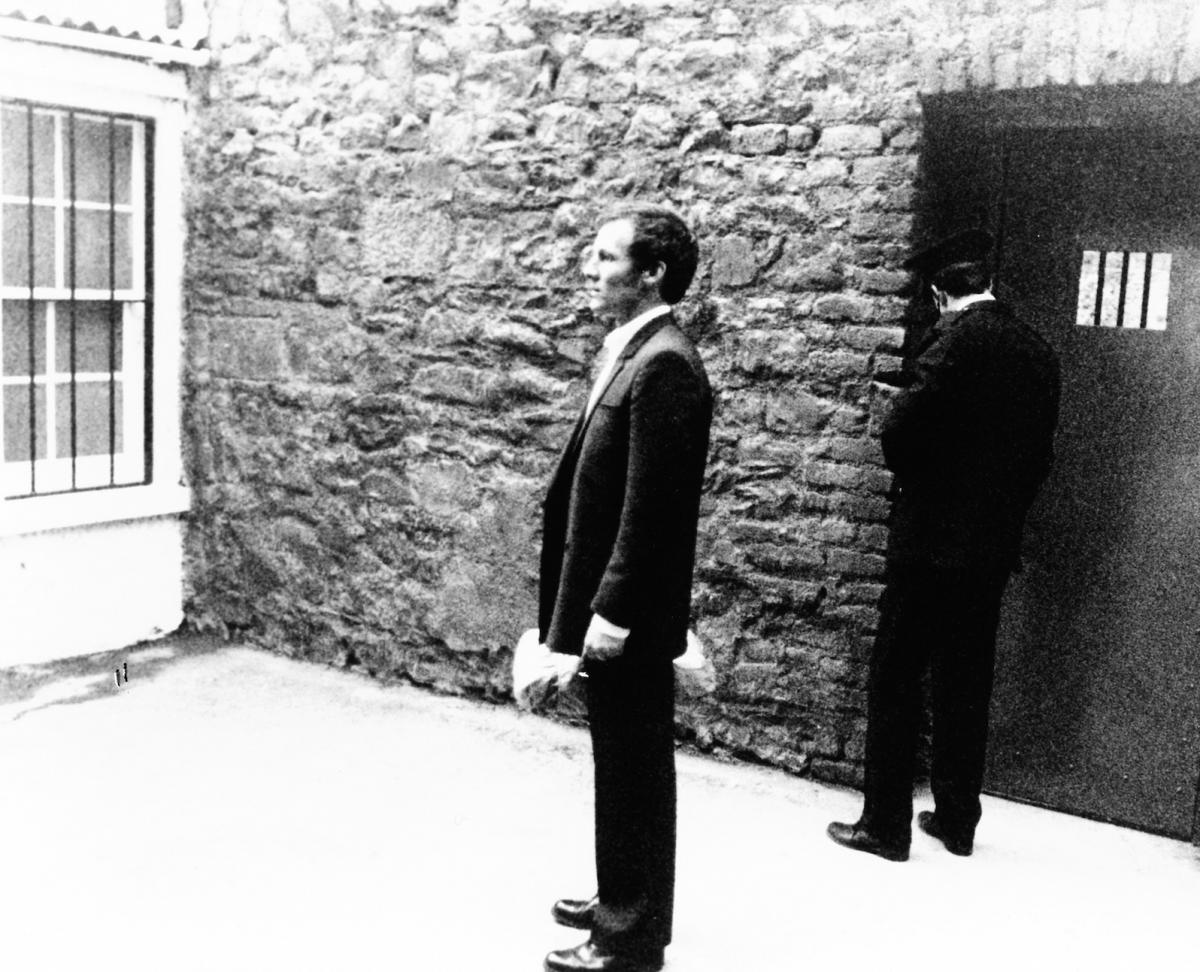

A Sense Of Freedom (18)

Odyssey, £12.99

Peter McDougall's shocking and hard-hitting screen adaptation of Jimmy Boyle's famous memoir is rightly acclaimed. But as much as it points an accusing finger at the brutality of the Scottish prison system and the poverty of aspiration that turned young men into thugs, so should its very existence make us cast reproachful looks at the medium that aired it: television. It was commissioned by STV and screened in 1981, a fact that's pretty hard to comprehend when you glance at the low-brow dross that makes up the schedules today.

And while we're on the subject of blame, this re-issue includes the later version which was cut and (an even worse crime) dubbed. Hilariously, the disc is even stamped with the words “A Sense Of Freedom (English Version)”. Sadly, it's this one which is often shown on TV.

Why are you making commenting on The Herald only available to subscribers?

It should have been a safe space for informed debate, somewhere for readers to discuss issues around the biggest stories of the day, but all too often the below the line comments on most websites have become bogged down by off-topic discussions and abuse.

heraldscotland.com is tackling this problem by allowing only subscribers to comment.

We are doing this to improve the experience for our loyal readers and we believe it will reduce the ability of trolls and troublemakers, who occasionally find their way onto our site, to abuse our journalists and readers. We also hope it will help the comments section fulfil its promise as a part of Scotland's conversation with itself.

We are lucky at The Herald. We are read by an informed, educated readership who can add their knowledge and insights to our stories.

That is invaluable.

We are making the subscriber-only change to support our valued readers, who tell us they don't want the site cluttered up with irrelevant comments, untruths and abuse.

In the past, the journalist’s job was to collect and distribute information to the audience. Technology means that readers can shape a discussion. We look forward to hearing from you on heraldscotland.com

Comments & Moderation

Readers’ comments: You are personally liable for the content of any comments you upload to this website, so please act responsibly. We do not pre-moderate or monitor readers’ comments appearing on our websites, but we do post-moderate in response to complaints we receive or otherwise when a potential problem comes to our attention. You can make a complaint by using the ‘report this post’ link . We may then apply our discretion under the user terms to amend or delete comments.

Post moderation is undertaken full-time 9am-6pm on weekdays, and on a part-time basis outwith those hours.

Read the rules here