Garry Scott

It's not every day you see a motorcycle being born. Its engine firing into life for the first time, wheels rolling as it begins its journey. The technicians standing around like proud midwives. I can't help but wish it well and hope it has a long and happy life. That's how sad I am.

I'm in the Ducati factory in Bologna and I had to get up at 6am in the middle of a family holiday to make it here for 9am, braving the truck-filled tunnels and bridges that carve through the rugged Apennine mountains between Florence, the cradle of the Renaissance, and industrial Bologna.

You know what they say about Italian drivers? It's all true. At one point, I glance in the rear view mirror and think a family that's definitely not mine has squeezed into the back seat only to realise they are actually glued to my bumper in a Fiat 500.

But the early start is worth it when I drive down Via Antonio Cavalieri Ducati (now there's a name for a street), and see the whitewashed walls with giant 30ft high paintings of sporting heroes such as Troy Bayliss and Carl Fogarty.

Later, when I tour the factory's museum, and see the priceless machines ridden by everyone from Paul Smart to Casey Stoner the curator says I look like a child on Christmas Day. And that's very much how I feel.

But let's go back to the beginning. Back to October 12, 1944, when allied bombers dropped more than 850 bombs on the factory. The plant, which specialised in radio equipment and had been seized by the Germans after the Italians signed an armistice with Allies, was destroyed. But it was to be not the end but a new start.

After the war the factory was rebuilt and the Ducati brothers – Bruno, Adriano and Marcello – patented a small clip-on engine for bicycles. The 48-cc 4-stroke engine, called Cucciolo (puppy) produced 1.5bhp and is the father of every Ducati engine since – right up to the rumoured new 220bhp V4 road bike.

The factory tour begins with my guide handing my son and me stickers to put over our phone cameras. There must be no photography. My hopes of catching a glimpse of the top secret V4 are dashed.

The factory is a revelation. It's nothing like those high-tech car plants you see on the news, where shiny robots outnumber humans. Here, every bike is put together by hand in a factory that is not too dissimilar to the one where the Cucciolo was born in 1946 – although obviously the tooling is a bang up to date.

Each bike begins on the assembly line, and the same worker follows it through the build as it moves slowly along through each station. It all begins, fittingly for a Ducati, with the engine. Then the exhaust is fitted, after that the frame, and the rear wheel. At each stage, when the worker completes a task, they cross to a computer, which then logs and checks their work, for example, ensuring that each bolt is tightened to the correct torque.

At peak times, the factory – and it is the only Ducati factory, there is no plant churning out bikes in low-wage Asia or India – produces 350 bikes a day. A Scrambler can be built in seven hours, a Multistrada takes a little longer at 10 hours. (Camshafts and crankshafts have already been through 34 days of milling).

We pass the race department but it's all secret squirrel. It's no wonder. Ducati is tiny compared to the Japanese giants but you wouldn't know that by their MotoGP results this year. They may not yet be back to the glories of 2007 when Stoner won the championship but behind that door they are plotting to give this year's hopeful, third-placed Andrea Dovizioso a chance at the title.

I watch a Diavel being put through its final testing in a noise-proof station, it's engine running for the first time, as a technician checks it over. From there, the bike is undressed – fairings and seats removed – and it's ready to ship. Maybe it'll end up in Scotland.

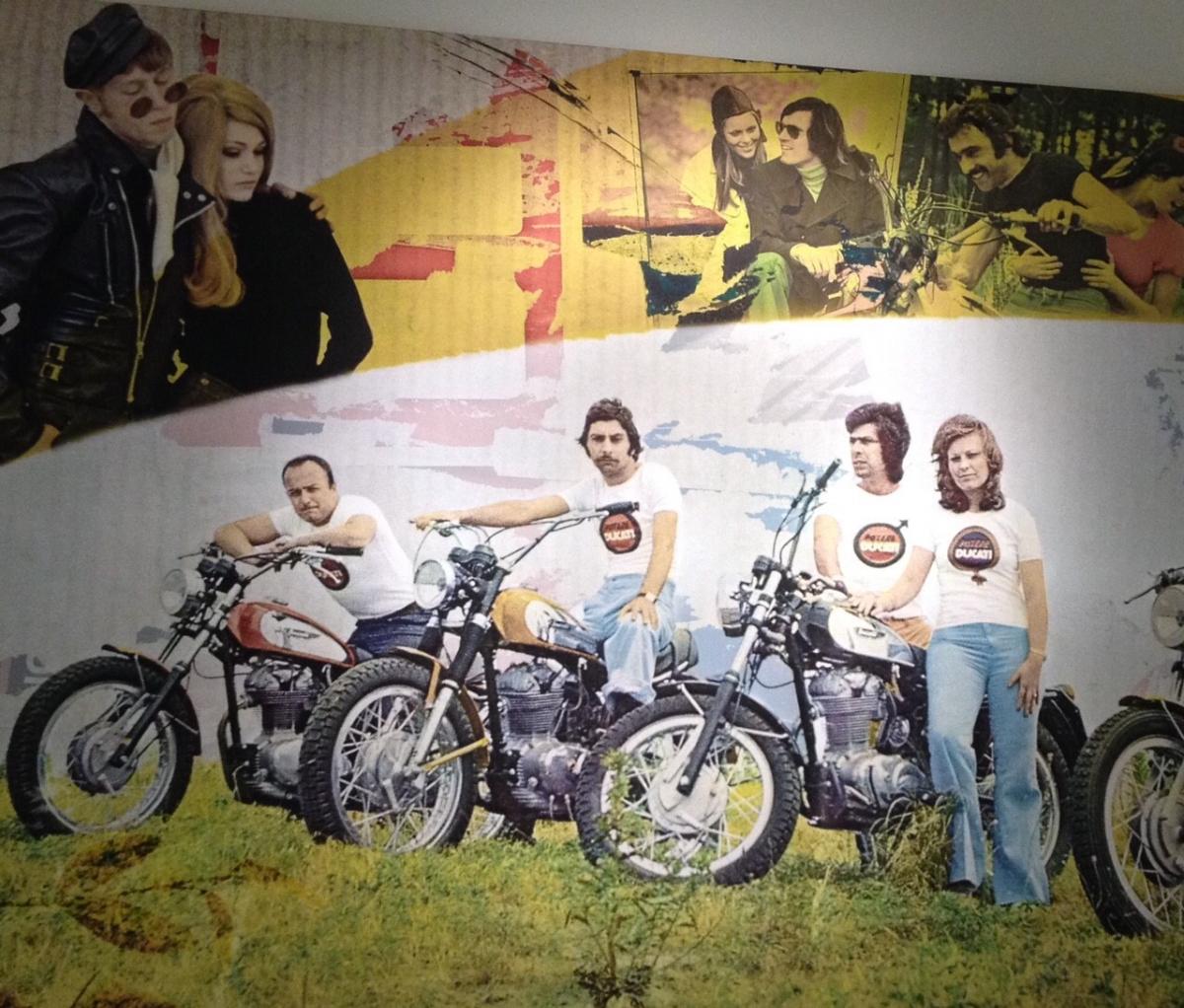

I cross to the museum to meet curator Livio Lodi. He's an engaging soul bubbling over with tales about Ducati and their place in Italian culture. He says the museum is the second most visited in Bologna after the Archaeological Museum, which is one of Italy's most prestigious archaeological collections.

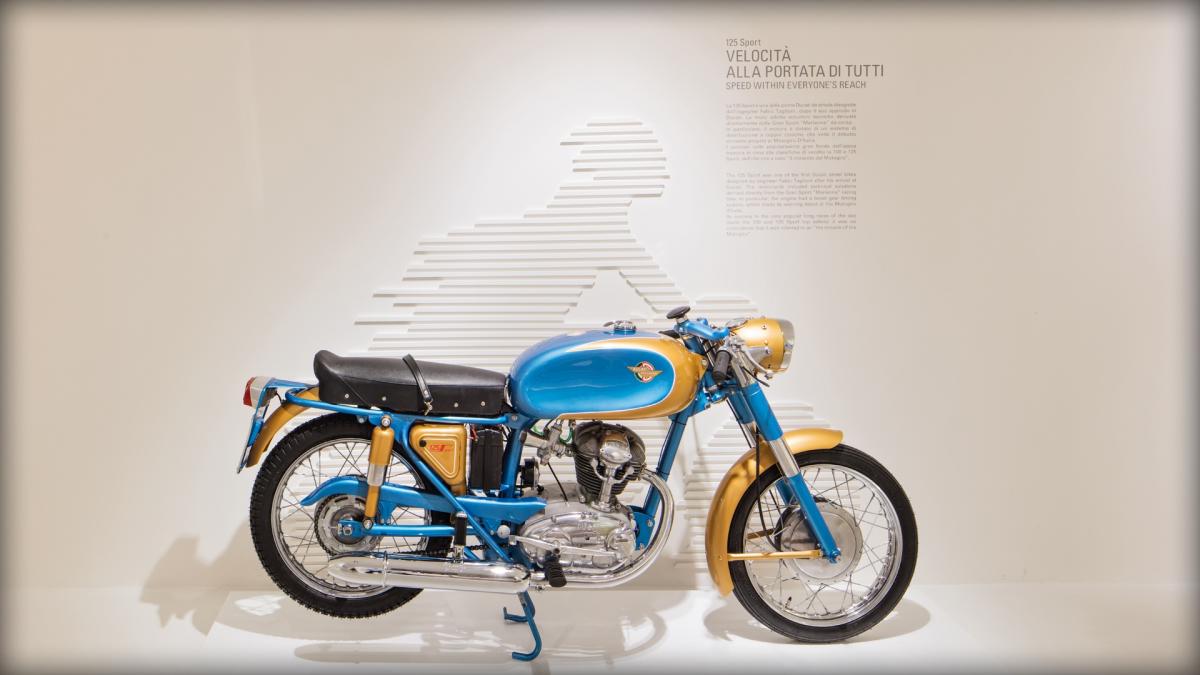

The collection tells the story of Ducati from the earliest days, with English translations on each information board. The key bikes and the stories behind them are all there: the 500 Pantah, the Monster, the 916, even the generally unmourned 750 Paso.

I see the bikes ridden by Mike Hailwood and Neil Hodgson, the grips that they twisted as they rode to glory in the Isle of Man TT and World Superbikes. You can't help imagining yourself stretched out across the tank, duelling for victory against the best in the world. It's intoxicating stuff.

There are leathers belonging to Stoner (he's wee, very wee) and race winners' cups. There is also, touchingly, the late Nicky Hayden's Ducati.

Possibly though, the most interesting exhibit tells the story of Tartarini and Giorgio Monetti who, in 1957, completed a 40,000-mile voyage around the world, which took the two riders across five continents and 36 countries on their 175cc 14bhp singles. Now that puts Ewan McGregor and Charley Boorman's big trips on big BMWs into perspective.

As I leave I spot a sign outside that reads Parking For Employees' Ducatis Only. I think it's a joke but Livio says no. It seems turning up to work on anything else might not be a treasonable offence but it comes close in this part of Italy.

Factory and museum tours can be booked in advance at

www.ducati.com/ducati_museum/index.do

@garryscott7

Why are you making commenting on The Herald only available to subscribers?

It should have been a safe space for informed debate, somewhere for readers to discuss issues around the biggest stories of the day, but all too often the below the line comments on most websites have become bogged down by off-topic discussions and abuse.

heraldscotland.com is tackling this problem by allowing only subscribers to comment.

We are doing this to improve the experience for our loyal readers and we believe it will reduce the ability of trolls and troublemakers, who occasionally find their way onto our site, to abuse our journalists and readers. We also hope it will help the comments section fulfil its promise as a part of Scotland's conversation with itself.

We are lucky at The Herald. We are read by an informed, educated readership who can add their knowledge and insights to our stories.

That is invaluable.

We are making the subscriber-only change to support our valued readers, who tell us they don't want the site cluttered up with irrelevant comments, untruths and abuse.

In the past, the journalist’s job was to collect and distribute information to the audience. Technology means that readers can shape a discussion. We look forward to hearing from you on heraldscotland.com

Comments & Moderation

Readers’ comments: You are personally liable for the content of any comments you upload to this website, so please act responsibly. We do not pre-moderate or monitor readers’ comments appearing on our websites, but we do post-moderate in response to complaints we receive or otherwise when a potential problem comes to our attention. You can make a complaint by using the ‘report this post’ link . We may then apply our discretion under the user terms to amend or delete comments.

Post moderation is undertaken full-time 9am-6pm on weekdays, and on a part-time basis outwith those hours.

Read the rules hereComments are closed on this article