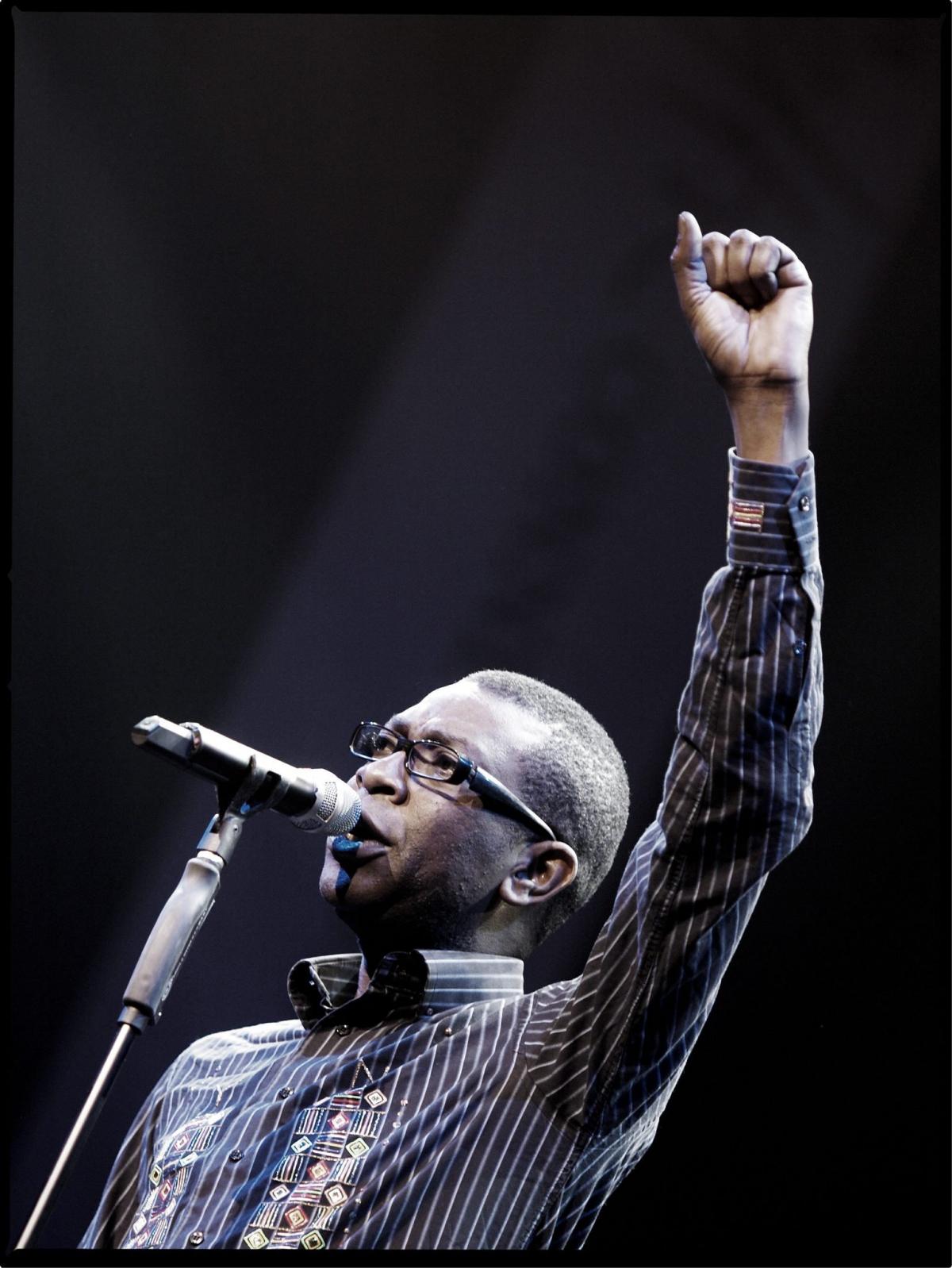

THE APPEARANCE of Sengalese superstar Youssou N'Dour at the Usher Hall during this year's Edinburgh International Festival is much more than a highlight of a new direction in EIF programming, it is a major cultural event.

I first saw West Africa's senior cultural statesman perform live in 2008 on Senegal's Independence Day, April 4, and I was among a crowd who waited over three hours for the singer to appear at Thiossane, N'Dour's club in Dakar. The gig was advertised by word of mouth: I couldn’t find it in any official listings, and the set time I was given by Dakar’s taxi drivers and youth hostel clerks was simply "evening". As the hours dragged past, I started to get a sense – the same sense I often had waiting around for Senegalese public transport – that I might have been sold a line. That uncertainty merely added to the feeling of an approaching epiphany, however, and then the sense of unabashed, starry-eyed wonder when N’Dour and his band, the Etoile de Dakar, finally did appear.

It is no understatement to say Youssou N’Dour has one of the most remarkable voices on the planet. For me, he’s up there with Sheila Stewart, Nina Simone and Tim and Jeff Buckley. It has been said Youssou has a staggering seven-octave range, which if true, would put him head-and-shoulders above Mike Patton’s mere six and Axl Rose’s pitiful five. Seven octaves or not, N’Dour’s range is simply confounding, and he uses each and every semitone of it, from sky-shattering soprano to bluesy baritone. There’s a sense of desperate joy, or joyous desperation when N’Dour hits one of his trademark, ceiling-scratching high notes; the same all-in, uncompromising commitment and vulnerability you hear in Stewart’s Queen Amang the Heather and Simone’s coda to Sinnerman. Given Youssou’s ties to Senegal’s traditional griot caste (singers, storytellers and custodians of oral history) and his frequent use of devotional registers, it’s easy to start hearing an immeasurable depth of time and experience in that voice. To recall the heady hyperbole of Rolling Stone magazine, it is "a voice so extraordinary that the history of Africa seems locked inside it".

For those as-yet unfamiliar with West African music, cultural osmosis will probably mean N’Dour comes most readily associated with 7 Seconds, his 1994 duet with Neneh Cherry. That’s a little like knowing Bjork for It’s Oh So Quiet, for 7 Seconds is just the familiar tip of a lesser-known but infinitely more significant iceberg. If you haven’t already heard it, then you owe it to yourself to seek out Immigrés, the album that put N’Dour on the world music map in the 80s.

Immigrés is one of the most ecstatic, euphoric slices of Afro-fusion you’re likely to hear. It’s Miles Davis's Bitches Brew for a sunny day, Youssou’s voice as lucid and incisive as a trumpet amidst the Etoile’s dense thickets of percussion and brass. And once you’ve recovered from the sun-soaked punch of Immigrés, next you need to track down the Grammy-winning Egypt, N’Dour’s sublime, ascetic statement of Sufi faith. A devotional symphony placing the singer’s heavenly howl at the heart of an orchestra of traditional African instruments, Egypt is a profound work submerged with history that, when placed alongside Immigrés, is testament to N’Dour’s vision and versatility. Egypt has a similar place in N’Dour’s oeuvre to Glen Lyon in Martyn Bennett’s; it’s a relatively pared-back, purist statement, shorn of most of the trappings of fusion, the sound of a singular voice reconnecting with its roots.

It is difficult to talk about N’Dour’s remarkable musical output, however, without acknowledging the encroaching shadow of his equally larger-than-life presence in world politics. In Senegal, N’Dour owns a recording studio, a record label, one of the country’s most widely circulated newspapers, a radio station and a television channel. He has been a movie star (in 2006’s Amazing Grace), an ambassador for the UN and UNICEF, the instigator of numerous charitable ventures and foundations, and in 2012 took up office as Senegal’s Minister of Tourism and Culture. (On occasion, he has even expressed interest in being the first pan-national President of Africa.)

N’Dour’s largely progressive image within African politics has been not been without its darker side in recent years, in particular because of his decision to follow Senegalese polygamous tradition in taking a second wife in 2007, by insinuations of political impropriety (which saw N’Dour disqualified from the Senegalese prime ministerial race in 2012), and by the sneaking suspicion the man is something of a megalomaniac. N’Dour’s CV does, after all, verge on the absurd: a political figure who tours the world’s stadium-sized rock venues, whilst simultaneously courting Hollywood and fronting his own media empires. But whatever your views on N’Dour’s career, there’s no denying his chutzpah; the ambition is staggering.

So is N’Dour a progressive, populist figure in pan-African politics, or is he an unholy Senegalese mix of Kanye West and Bono? Whichever he is, there’s not denying That Voice; that enormous, sky-scratching, desperate, joyous voice. Don’t miss the chance to hear it for yourself when N’Dour plays Edinburgh during the festival. Unlike his word-of-mouth shows in Dakar, you can at least be sure of when and where he will be performing.

Youssou N'Dour is at Edinburgh's Usher Hall on August 24 at 8pm. www.eif.co.uk

Why are you making commenting on The Herald only available to subscribers?

It should have been a safe space for informed debate, somewhere for readers to discuss issues around the biggest stories of the day, but all too often the below the line comments on most websites have become bogged down by off-topic discussions and abuse.

heraldscotland.com is tackling this problem by allowing only subscribers to comment.

We are doing this to improve the experience for our loyal readers and we believe it will reduce the ability of trolls and troublemakers, who occasionally find their way onto our site, to abuse our journalists and readers. We also hope it will help the comments section fulfil its promise as a part of Scotland's conversation with itself.

We are lucky at The Herald. We are read by an informed, educated readership who can add their knowledge and insights to our stories.

That is invaluable.

We are making the subscriber-only change to support our valued readers, who tell us they don't want the site cluttered up with irrelevant comments, untruths and abuse.

In the past, the journalist’s job was to collect and distribute information to the audience. Technology means that readers can shape a discussion. We look forward to hearing from you on heraldscotland.com

Comments & Moderation

Readers’ comments: You are personally liable for the content of any comments you upload to this website, so please act responsibly. We do not pre-moderate or monitor readers’ comments appearing on our websites, but we do post-moderate in response to complaints we receive or otherwise when a potential problem comes to our attention. You can make a complaint by using the ‘report this post’ link . We may then apply our discretion under the user terms to amend or delete comments.

Post moderation is undertaken full-time 9am-6pm on weekdays, and on a part-time basis outwith those hours.

Read the rules here