Glasgow-based business Ambassador Group is developing almost 1,000 new homes at a former hospital site in Bangour Village Hospital in West Lothian. Here, Susan Swarbrick, recalls growing up in the shadow of the hospital.

THE windows and doors are boarded up, paint peeling like flaking skin and sections of the brickwork crumbling to dust. Nearby the jagged remnants of a fence resembles a row of rotting teeth. A warning has been spray-painted on many of the walls: "Danger, keep out!"

But if I close my eyes I can see it as it once was. The pristine exteriors and manicured gardens. I can smell the freshly cut grass out on the cricket field and hear the sound of a radio gently drifting from one of the wards.

In its heyday Bangour Village Hospital in West Lothian was a busy psychiatric facility. Today, though, the only noise is the distant hum of the M8, an occasional chirrup of bird song and the wind gently rustling the tree branches.

A gamut of memories swirls in my head as I walk through the grounds this winter afternoon. The paths are mossy and overgrown. Nature is reclaiming this place. The concrete underfoot is cracked with weeds sprouting, the signs and road markings faded.

Even so, I know my way around like the back of my hand. Over there is the shop and the recreation hall. Down that way is the boiler house and cricket field. Follow the road up through the trees and you'll find the bowling green.

The last of the patients left here in 2004. In the years since it has lain empty as NHS Lothian sought to find a buyer for the sprawling 215-acre site with its reported £8m price tag.

That search may be at an end. In recent days it has been confirmed that a developer is in advanced talks to purchase the land (with a sale expected to be confirmed by this weekend). But what next? Already there have been rumours swirling that the complex could be flattened to make way for houses.

On paper it sounds straightforward, but the reality is far less clear cut. There are 15 listed buildings at Bangour Village Hospital with the church and recreation hall Category A structures. For many who know Bangour, to see it demolished would feel akin to architectural vandalism.

My own ties to the hospital site run far deeper than simply bricks and mortar. I grew up less than half a mile away in the village of Dechmont. The Bangour story is one that is in my blood.

All these wards – villas as they were known – have numbers. Most have ghost stories. This big building I'm standing in front of? That's the nursing home. And it's where our story begins.

It was 1963 when my late father Alexander Swarbrick arrived to begin his training. He was 22. For the seven years previously, he had worked in a coal mine. As pit first aider, he proved himself blessed with cool head and strong stomach when faced with even the grisliest of injuries.

But it was healing broken minds rather than broken bones in which my father found his calling. He would spend much of the next two decades working at Bangour Village Hospital. It is him I think of as I wander among the neglected and abandoned buildings.

Later in the day I visit John Galvin, a retired nurse who did his psychiatry training at Bangour in the intake a few years after my father. They knew each other well. Galvin, 69, from Dechmont has happy memories of his time working at the hospital.

"I started off in Ward 4 which was known as psychogeriatric in those days," he says. "Then, because I was young and fit, they decided to send me up to the locked ward. I spent most of my training in Ward 25 which had the more at-risk patients with restricted access to the outside community."

Galvin developed a strong rapport with many of the patients he cared for. This was an era when the use of drugs to treat psychiatric conditions was still in its infancy. As a young nurse Galvin saw everything from psychosis and schizophrenia to post-traumatic stress disorder.

"There was one chap who was a patrician," he says. "He referred to himself as a Lord and would take umbrage if didn't address him as that. He once wrote me a cheque for £1m on a piece of toilet paper.

"Another guy was a fantastic table tennis player. He would always walk about with his collar turned up. We used to play him for a cigarette. No one could beat him. He never had to buy a cigarette."

The job wasn't without its challenges, however. "I once got a crack on the head with a urinal [bed pan]," recalls Galvin. "I was helping a man out of bed and he had it hidden under his pillow. As I swung him round to get his slippers on, he hit me over the head. Whack."

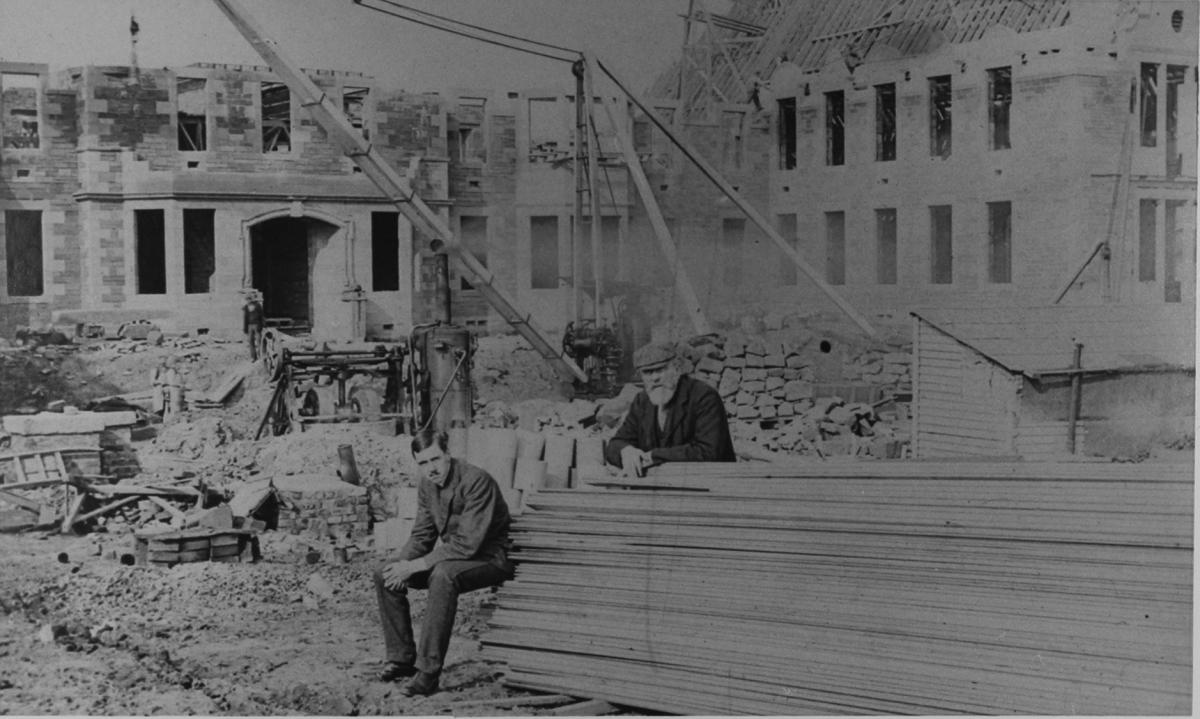

At its conception, Bangour was touted as revolutionary. Edinburgh architect Hippolyte J Blanc won the contract to design it in 1898. Modelled on the Alt-Scherbitz hospital near Leipzig in Germany, the idea was for psychiatric patients to be cared for within their own community setting.

This was in marked contrast to the Victorian era when mental illness was poorly understood and so-called "lunatic asylums" were largely dehumanising, prison-like institutions. Bangour was set-up on a village system of patient care, encouraging self-sufficiency and with few physical restrictions.

While the blueprint may have been pioneering, general attitudes to mental health still had much catching up to do in the early 20th century when Bangour was built by the Edinburgh District Board of Lunacy/Board of Control to house what was termed "pauper lunatics".

The location in itself was notable: land was purchased 14 miles west of Edinburgh which was deemed to be sufficiently far enough away from the Scottish capital to satisfy any concerns about safety, yet still within reach by means of a private railway.

The first patients were admitted in 1904 and Bangour Village Hospital – then called the Edinburgh District Asylum – officially opened to great fanfare two years later. Facilities included a farm, bakery, workshops, recreation hall, school and shop. A library and church followed in subsequent years.

The villa design of the wards drew on a 17th-century Scottish Renaissance style, while the recreation hall is Edwardian Baroque and the church neo-Romanesque.

Two other psychiatric hospitals were built in Scotland on the village system of patient care – Kingseat near Aberdeen and Dykebar Hospital in Paisley opened in 1904 and 1909 respectively – but these have not survived as completely as Bangour.

Much of my own childhood was spent in and around Bangour. It never felt like a frightening or creepy place. I knew many of the patients by name. Ditto most of the staff that worked there.

My brother and I were both christened in the church. As I got older and went out on adventures with my friends and our family's three-legged dog, I would often pop into the nearest ward for a biscuit and glass of diluting juice.

We would go sledging at the cricket field slopes and roll our hard-boiled eggs there at Easter. The best conker trees were next to the boiler house and there would be squeals of joy as pockets were filled with these shiny, mahogany-coloured treasures.

I loved riding my bike around the rambling paths that linked the buildings and would regularly sneak into the hospital dump in the hope of finding old wheelchair parts to build go-karts.

Throughout my life I have struggled to fathom the stigma that often surrounds mental health. Perhaps that is because it was never presented as something to be feared or hidden.

Even as a child it seemed remarkably simple to understand. Psychiatric care was no different to someone getting medical attention for a broken leg or a badly scalded hand: it was merely a less visible part of their body that required treatment.

Claire* was a regular visitor to Bangour Village Hospital during the 1980s and 90s where her mother was long-term patient. "I spent all my childhood – every night – visiting her," she says. "It wasn't a scary place at all.

"My mum had some awful medical procedures while admitted; for example, electric shock therapy [after which] she wouldn't even know my name when I would go to visit. But the other residents and staff made up for that and would keep me amused and even help me with my homework every night.

"I really don't have any horror stories about the place at all. People think I'm weird because I still say I had the best childhood. Even though my mum was sick, we were always with her and the Bangour community were all amazing people."

As Bangour Village Hospital wound down in preparation for closure in 2004, her mother was moved to the psychiatric wards in St John's Hospital at Howden, Livingston. "I found that more of a horrific experience and it was more like a 'hospital' than Bangour," she says.

"I've not been back to Bangour as I'm scared of seeing it run down and I don't want it to tarnish my memories."

My own father passed away from cancer six years ago. While writing this story for The Herald there has been countless times when I wished I could have called him up to talk about it.

He always spoke fondly of the patients he cared for, some of whom had a flair for escapology to rival Steve McQueen. On one occasion a patient made off with an idling mini bus when the driver briefly popped into a ward, leaving the keys in the ignition.

A few hours later the said bus thief made a sheepish telephone call to Bangour to confess he had abandoned the vehicle outside a pub in nearby Broxburn, but after a few pints had sensibly decided it wasn't a good idea to drive home.

Would my father send someone to pick him up please? Oh, and could they hurry? The group of elderly ladies still on board the bus were wanting their tea ...

My father later moved to Bangour General Hospital where he variously did clinical teaching, worked as a nursing officer on the surgical wards and was appointed to the commissioning team for the new St John's Hospital, which opened in 1989.

But it was Bangour Village Hospital that always held his heart. When he died in 2011, the funeral cortege paused by the main gate for a few moments. He would have wanted to say goodbye.

Now I must find my own way to say farewell.

Last summer I spent hours in the Lothian Health Services Archive held at Edinburgh University sifting through minutes, reports, staff records, ward case books and admissions/discharge registers. While I had heard some of it anecdotally before, the history was nothing short of fascinating.

Bangour Village Hospital was requisitioned to house the injured and convalescing during the First World War. A report by Edinburgh District Board of Lunacy/Board of Control details the years from 1915 to 1921 when the hospital was formally given over to the War Office.

It reads: "When cases of malaria and dysentery began to arrive in large numbers from East Africa, Gallipoli, Salonika or Palestine, Bangour became the centre in Scotland for tropical diseases.

"It was found that Bangour, with its elevated situation and bracing climate, was particularly suitable for malaria cases.

"Later, when limbless men in ever increasing numbers were being admitted and retained until their stumps were ready for the fitting of their artificial limbs, Bangour was selected as the preparatory hospital for Scotland."

There were more than 3,000 beds at Bangour, covering surgery, general medicine and tropical diseases during the First World War. In the fortnight following July 1, 1916, three ambulance trains arrived at Bangour bringing 550 wounded men from the Somme.

During this period, the lion's share of the 862 psychiatric patients had been sent to other facilities across Scotland or handed over to the care of relatives.

Interestingly, however, the report states that: "48 quiet and useful men, accustomed to work on the farm or in the gardens or grounds" and "45 quiet and useful [women], accustomed to help in the central kitchen or laundry" remained to assist the war effort in these areas.

Bangour Village Hospital was requisitioned again during the Second World War. In 1939, an annexe constructed from prefabricated huts was built on the north-west of the site to help accommodate the incoming war casualties.

Afterwards it became Bangour General Hospital which housed a variety of medical fields including an A&E, maternity unit and specialist treatment in burns and plastic surgery. It closed in the early 1990s and was demolished following the opening of St John's.

Today nothing remains of Bangour General Hospital. It would be heartbreaking to see Bangour Village Hospital go the same way.

This is a sentiment echoed by Harriet Richardson, an architectural historian at University College London's Bartlett School of Architecture.

Fife-based Richardson worked on a survey of hospital architecture across Scotland between 1989-90 and did a similar four-year project in England. More recently, she created the Historic Hospitals website, an architectural gazetteer based on this research.

"There weren't very many former psychiatric hospitals built on that village plan," she explains. "Almost none in England. There was a small group that were built in Scotland. Bangour is the most complete and best architecturally."

Richardson is keen to see this preserved as much as possible in any future development. "The buildings are eminently convertible," she says. "The main problem is that it is cheaper to knock something down and start afresh than it is to salvage an old building and give it new life."

She cites the former Three Counties Asylum in Bedfordshire as one example of a sympathetic conversion of a hospital into housing.

"They have kept the main asylum building group, its gardens and immediate surroundings, and put a big village development to the north and south. It is not perfect, but it is a pretty good compromise. They have taken off some of the later additions to the site, although kept the core of it."

Another example, says Richardson, is the former Royal Earlswood Hospital in Redhill, Surrey. "It's this big, imposing Gothic pile and they use all that great architecture as a selling point. It has been made into luxury flats and a gated community, but they have preserved the buildings.

"The ones that have been done best tend to be close to a big city. So, you would think there might be a chance that Bangour would appeal to the Edinburgh commuter. If only there were more financial incentives for developers to do the best thing."

She is realistic that not everything can be saved. "What happens is they often gut out the interiors which upsets purists on the conservation side. You have that inner battle: 'Now you have completely gutted it to a shell, was there any point?'

"I'm not quite so fussy. I think you need to be pragmatic. If you can still see the essence and keep some of the spaces around it, then that is the key thing."

What would it pain her the most to see disappear from Bangour? "Any of the original group of villas, the recreation hall and church," says Richardson. "There are some slightly later peripheral, single-storey wards which were for the physically sick, such as isolation wings for TB.

"While they do have architectural merit in my view, if it was a straight choice then it does tend to be the more peripheral ones that are often sacrificed."

There have been flurries of short-term activity on the site. Bangour served as a location for the 2005 film The Jacket, produced by George Clooney and starring Keira Knightley and Adrien Brody.

In 2009, the grounds were used for "Exercise Green Gate", a counter-terrorist exercise run by the Scottish Government to test decontamination procedures in the event of a nuclear, chemical or biological incident.

Recent years have seen the future of Bangour remain in limbo. A planning application for a housing development was submitted in 2004 by Persimmon Homes, but they withdrew their bid in 2008, citing the economy's downturn.

Talks between a Birmingham-based Islamic trust, NHS Lothian and West Lothian Council for turning it into a residential university also fell through in 2011.

The latest to show an interest is developer Allanwater Homes. According to a statement given to The Herald at time of going to press: "Allanwater are having a dialogue with the NHS. A bid has been put in."

How that pans out will be critical. No one is expecting Bangour to be preserved as a pristine time capsule, but it would be heartening to see a new and positive chapter in its story unfold.

*name changed

This feature originally ran in February 2018

Why are you making commenting on The Herald only available to subscribers?

It should have been a safe space for informed debate, somewhere for readers to discuss issues around the biggest stories of the day, but all too often the below the line comments on most websites have become bogged down by off-topic discussions and abuse.

heraldscotland.com is tackling this problem by allowing only subscribers to comment.

We are doing this to improve the experience for our loyal readers and we believe it will reduce the ability of trolls and troublemakers, who occasionally find their way onto our site, to abuse our journalists and readers. We also hope it will help the comments section fulfil its promise as a part of Scotland's conversation with itself.

We are lucky at The Herald. We are read by an informed, educated readership who can add their knowledge and insights to our stories.

That is invaluable.

We are making the subscriber-only change to support our valued readers, who tell us they don't want the site cluttered up with irrelevant comments, untruths and abuse.

In the past, the journalist’s job was to collect and distribute information to the audience. Technology means that readers can shape a discussion. We look forward to hearing from you on heraldscotland.com

Comments & Moderation

Readers’ comments: You are personally liable for the content of any comments you upload to this website, so please act responsibly. We do not pre-moderate or monitor readers’ comments appearing on our websites, but we do post-moderate in response to complaints we receive or otherwise when a potential problem comes to our attention. You can make a complaint by using the ‘report this post’ link . We may then apply our discretion under the user terms to amend or delete comments.

Post moderation is undertaken full-time 9am-6pm on weekdays, and on a part-time basis outwith those hours.

Read the rules here