ONE hesitates to use the traditional theatrical expression of good luck when wishing Alan Bissett well on his next play.

“Break a leg”, after all, might have unfortunate associations with Graeme Souness, the flawed, brilliant, fascinating and undeniable hero of the Scottish writer’s play that is scheduled to premiere next summer.

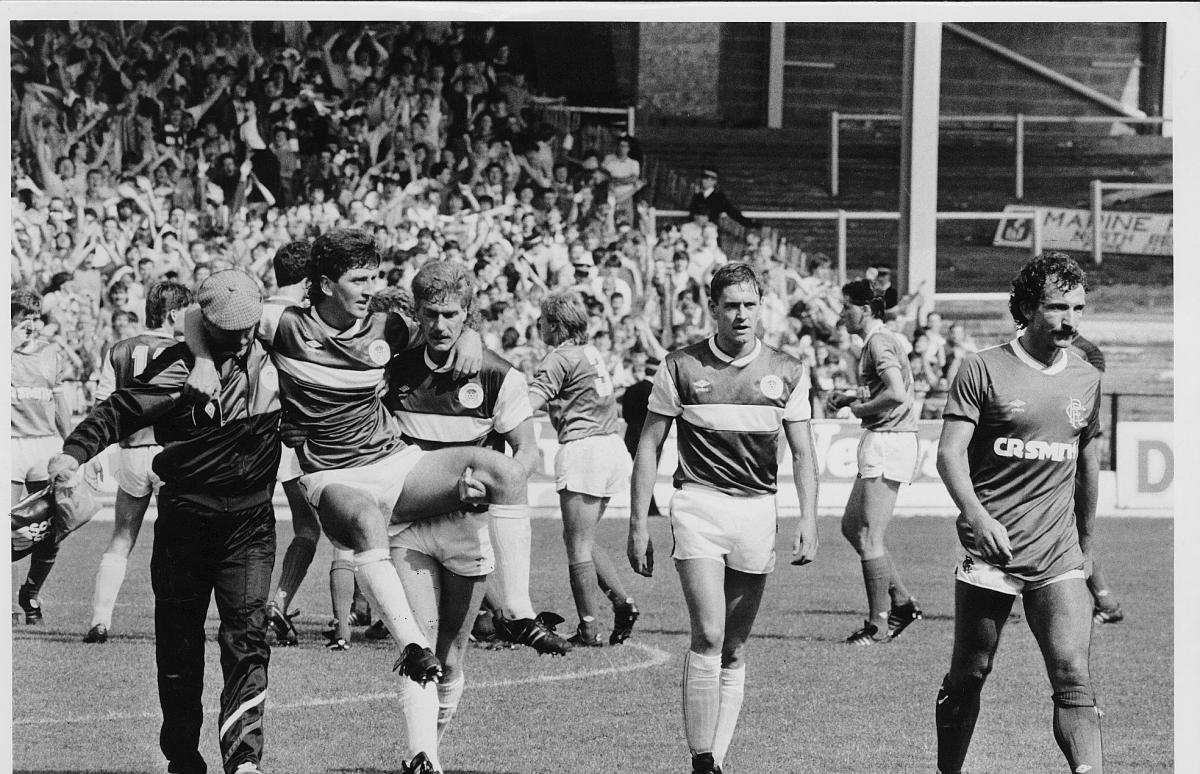

It is almost 29 years to this day (August 9, 1986) since Souness marked his debut as Rangers player-manager by marking George McCluskey’s leg with a challenge that was wilfully reckless yet so much part of the player’s make-up that it could have been used as DNA evidence. Souness was class, thuggery, sophistication and confrontation wrapped up in a mean frame and decorated with ‘tache and topped off with perm.

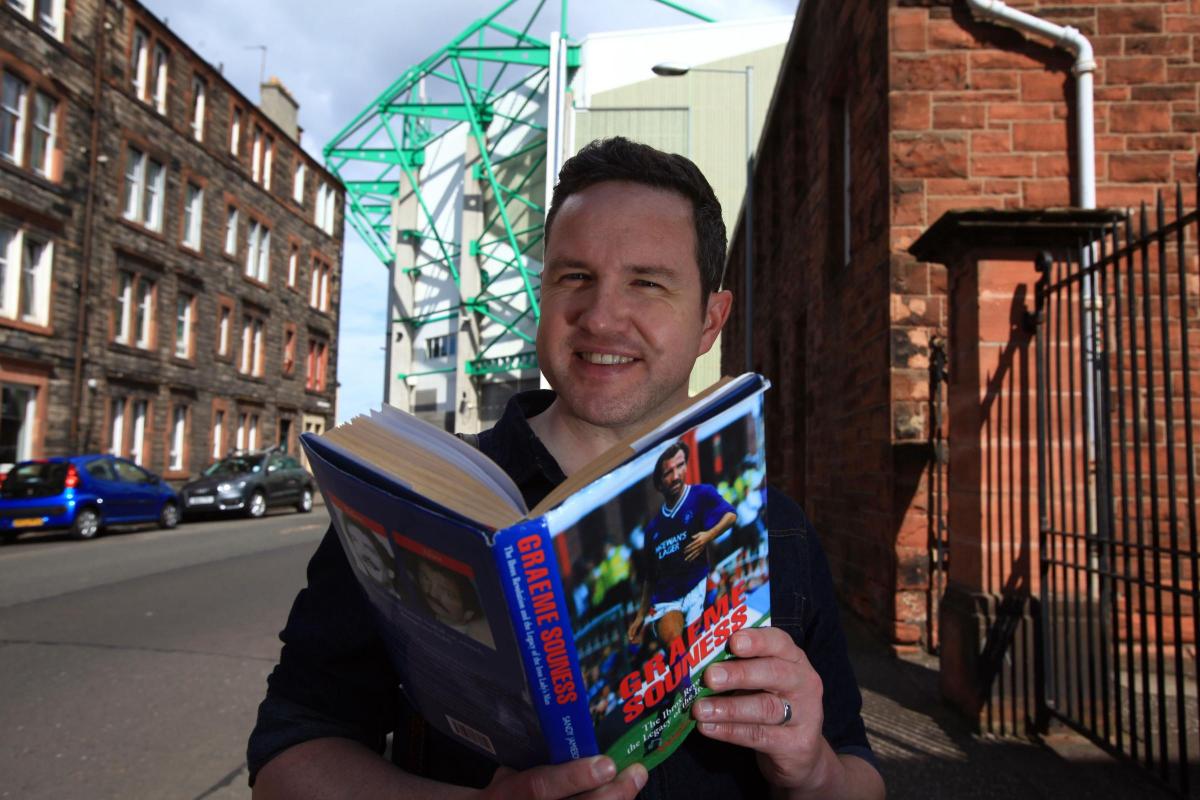

Bissett meets the challenge of addressing the myth, legend and substance of Souness by taking an approach that, in its almost reckless gallusness, invites the description of “studs up”.

Not only will Bissett bring an aristocrat of the game to the masses but he will do so in pointedly Shakespearean fashion, most particularly in verse.

Oh, and Bissett wants to play his hero on stage. The first reaction to this revelation is to remove one’s chin from the pub table as the writer sits on the other side with a grin as wide as a World Cup goalscorer. The second is to appreciate that Bissett has a facility for overturning the orthodox and making his own destiny with a mixture of chutzpah, talent and an extraordinary freshness of style and subject.

There is nothing surprising about a working-class boy graduating from Stirling University and becoming an award-winning author.

But Bissett confounds stereotypes by being the Rangers supporter who voted Yes, the personality who engages in debate while shrugging off criticism, the writer who is prepared, indeed, desires to be a performer.

“I would love to play Souness,” he says. “The director says I can audition but I will only get the part if there is no better Souness out there.”

But what of the one authentic Souness who is out here, who exists for most of the world as a television pundit with a hinterland of success, failure and even redemption?

Bissett, at 39, researched his subject as a boy, entranced by Rangers and the figure who was leading them to triumph, controversy and, with hindsight, to perdition.

“Everything that has happened at Rangers and in Scottish football since is an indirect result of the Souness era,” he says. “That is not to say that it is all his fault. Rangers were not liquidated because of Graeme Souness but that spend, spend, spend philosophy was part of football being tuned into a business. Rangers were at the cutting edge of that,” he says.

He makes a persuasive case that Rangers bringing top English players, introducing debentures and speculating without restraint was the football equivalent of the de-regulating of the markets.

“Souness was Scottish football’s Thatcher,” he says. The subsequent unlimited credit and the inevitable crash made Dick Advocaat, and his £12m signing of Tore Andre Flo, Rangers’ Gordon Brown. Bissett’s view of Souness, then, is ambivalent, even as contradictory as the subject himself.

The writer’s hero – as player and manager – has given him the warm memories but also a cold appreciation that not only is greed not good but it has consequences. Bissett thus can use the sport as a political and philosophical football. He has employed his craft to talk of the importance of football and its significance to him. He talks of how it binds him to his father who now lives in England. “His first question when we meet up is to discover just what is happening at Rangers,’’ says Bissett, who is a light-blue with a particular stripe.

“I think that if you are a Rangers fan now there is a frustration over why Scotland does not understand you, even hates you. Rangers are easily the most hated club in Scotland. Now that did not matter until Rangers were liquidated and were looking for support of other clubs that did not come. I noticed it then, the rancour that a lot of fans felt at a subliminal level for Rangers had come pouring out.”

Bissett, too, has argued in print and on television and radio for Scottish independence. He never saw Unionism as part of being a Rangers supporter. “I was aware the Unionist stuff was there but it was not relevant to me. I simply do not feel it is the case that the vast majority of Rangers fans feel Unionist. They might feel an allegiance to the club – they are aware of all the stuff that comes with that and might defend it when it is under attack – but they are not going to go home to salute the Queen.

“That Unionist element of Rangers fans is very vocal but there is a large amount of Rangers supporters who simply just want the team to win and the political element does not mean as much to them as people think.”

He accepts that some of the Rangers support feels marginalised politically by the nationalist surge. “Scotland has changed, Scottish nationalism is in the ascendancy and if you are a Unionist diehard you will feel under siege. There is that terror of no longer being relevant, of losing control.’’ His political views have caused some confusion. “The cliched response is when Yes folk say: ‘How can you be a Rangers fan and support independence?’ I am and can. I am frustrated at all Rangers supporters being lumped together.”

He adds: “I can reconcile quite easily wanting Rangers to win trophies and wanting Scotland to be independent. But I accept I am mistrusted by an element in Scottish nationalism for being a Rangers fan and by some Rangers fans for supporting independence. But this the most interesting place to be.’’

Bissett, of course, has explored Scottish football before, most notably in the novels Boyracers and Pack Men, and believes sport has "an intellectual credibility”. He knows this sort of phrase would invite a kick in the testimonials in his native Hallglen, Falkirk, but that does not make it untrue. “The simple fact is that football is integral to Scottish culture,” he says. “I wonder if the reason it was ignored in the past was because it was a working-class game. That changed in the nineties. It became a corporate game. It has been taken away beyond the reach of some working-class people.

“But if you are writing novels about working-class men then you must write about football, film, music. That is what men talk about. How can I write about the culture I came from without writing about football? It is a way men communicate with each other for better or for worse. It is about men’s relationship with their fathers, it is about men’s relationship with their workmates. It is about masculinity as a construct.”

It also carries the heavy burden of anger, even hatred. “People take the defeat of their football team as the defeat of themselves.”

Souness famously took defeat as a personal insult that had to be avenged, even as a prospect rather than a reality. “He is a great leader,” says Bissett of the Liverpool, Sampdoria and Rangers player who achieved fame and notoriety on the pitch and off it. He was the artist who could construct the perfect pass. He was the personality who could destroy the opposition through skill or violence. He was the manager who existed on confrontation. With the opposition, with fans, with his players.

"Flawed leaders are fascinating to dramatists. Look at Shakespeare: Coriolanus, Macbeth, Titus Andronicus, Lear. It is about power: how it shapes and motivates, and Souness personifies that. There is hubris too in the Souness story.”

Bissett points out correctly that Souness was central to ending Rangers' sectarian signing policy, was the Scottish piper who lured great players north of the border, was the massive speculator in the transfer market who changed Rangers forever, who unwittingly placed the foot on the accelerator of a Sir David Murray vehicle that was heading towards a grim reckoning.

At the height of his fame and powers in Scotland, the hero heads to England, back to Liverpool, as manager rather than player. “He then just f***s up,” says Bissett of the decline and fall. “He makes wrong decisions at a football level but the key moment is when he gives an interview to the Sun on the anniversary of the Hillsborough disaster.’’ The Rupert Murdoch newspaper had scandalised the city with its false reports of what happened on a tragic day that claimed 66 lives. The hero was thrown from the pedestal. “From then he could not command respect and that must have been painful,” says Bissett.

But there is redemption. Souness, who has endured heart problems, has found a serenity that many would have believed impossible. “He has changed. He knows he made mistakes. He knows he took things too far,” says Bissett.

But key to the rise and the fall was that belief in his self that was almost un-Caledonian. “He lived to rebut stereotypes. He hated that belief that Scottish teams were destined to lose,” says Bissett, pointing out that a chapter in Souness’s autobiography was entitled Sometimes I Wish I Was English.

The play will include a Hibs scene. That moment when Souness left his card of introduction on an unsuspecting shin.

“It was an extraordinary start to his reign; in retrospect, a totally fitting start. From that moment Souness was on a constant war footing with other teams, the SFA, referees, media, his own players and, to a certain extent, his own fans. He believes he is standing alone in a world out to get him.”

It has the essence of great drama and Bissett is taking a creative midfield role in supplying the supporting cast. Terry Butcher, the English captain, will be portrayed as an Anglo knight, Ally McCoist, a sometime irritant to Souness and a regular redeemer, will play the joker, there will be the Mo Johnston monologues where the striker will explain what it is like to be hated by sections on either side of the Old Firm divide. But Souness will be centre stage.

“I met him briefly at a night in the Louden Tavern,” says Bissett of a rendezvous with hundreds of other admirers at the Rangers pub. “He was there in a sort of ‘audience with’ night and it was spectacular. I am used to book festival dos when you sit on stage with an interviewer and there are questions afterwards. This was different. He stood behind a table as fans chanted Soooooo-Ness, Soooooo-Ness with a forest of fingers pointed towards him.”

And did he address the great man? “Yeah, I told him I had written a play about him. He just said: ‘It better be complimentary’.”

Break a leg, Alan. Break a leg.

Why are you making commenting on The Herald only available to subscribers?

It should have been a safe space for informed debate, somewhere for readers to discuss issues around the biggest stories of the day, but all too often the below the line comments on most websites have become bogged down by off-topic discussions and abuse.

heraldscotland.com is tackling this problem by allowing only subscribers to comment.

We are doing this to improve the experience for our loyal readers and we believe it will reduce the ability of trolls and troublemakers, who occasionally find their way onto our site, to abuse our journalists and readers. We also hope it will help the comments section fulfil its promise as a part of Scotland's conversation with itself.

We are lucky at The Herald. We are read by an informed, educated readership who can add their knowledge and insights to our stories.

That is invaluable.

We are making the subscriber-only change to support our valued readers, who tell us they don't want the site cluttered up with irrelevant comments, untruths and abuse.

In the past, the journalist’s job was to collect and distribute information to the audience. Technology means that readers can shape a discussion. We look forward to hearing from you on heraldscotland.com

Comments & Moderation

Readers’ comments: You are personally liable for the content of any comments you upload to this website, so please act responsibly. We do not pre-moderate or monitor readers’ comments appearing on our websites, but we do post-moderate in response to complaints we receive or otherwise when a potential problem comes to our attention. You can make a complaint by using the ‘report this post’ link . We may then apply our discretion under the user terms to amend or delete comments.

Post moderation is undertaken full-time 9am-6pm on weekdays, and on a part-time basis outwith those hours.

Read the rules hereLast Updated:

Report this comment Cancel