Simon Grennan, academic, artist and creator of new graphic novel Dispossession, tells us why comics rule...

What do I like about making and reading comics? There's still a kind of underdog status about comics, at least in English, that's belied by the massive power, joy and versatility of the medium.

That means that a good comic is like a sucker-punch: it always smacks you where you least expect it, partly 'cause it's always still 'a comic'. For folks who read comics, this is a de-facto definition of the medium that, in some way, seems to be connected to drawing.

"It's a bunch of drawings" is true of comics.

Then something happens and, if it's a good comic, it's something pretty left-field. For those who make comics, learning how to handle that sucker-punch quality is part of the challenge, the satisfaction or the creative despair: it's pretty hard to do.

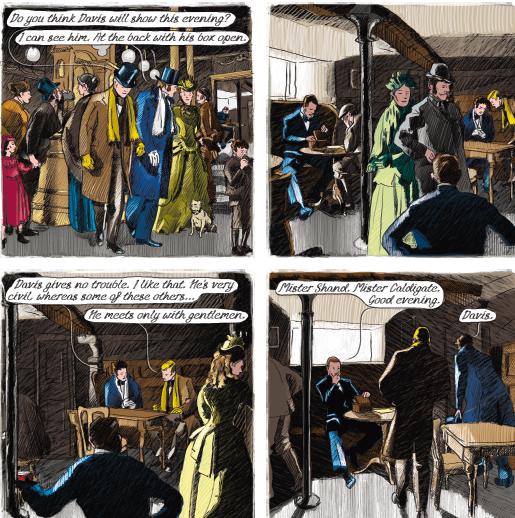

When I was drawing Dispossession, my new graphic adaptation of one of the later novels of the nineteenth-century author Anthony Trollope, I employed exactly this "what the...?" effect to produce the reader's sense of the deep strangeness of the 1870s, the Victorian period in which Dispossession is set.

It was a way of yanking my graphic novel away from costume drama where, pretty often, things seem lamely like they are today, but in fancy dress. Rather, comics' ability to surprise and manipulate the reader allowed me to set up unfamiliar points of view, half-buried systems of page layout and rhythm and a seductive and heavy-duty palette.

What I'm saying is that Dispossession is an immersive and unusual read. In this case, the sense of being unusual attaches itself to the readers' experience of the past. But I'd say that all good comics are unusual comics. That's why comics rule.

Simon Grennan’s gorgeous new graphic novel Dispossession, a tale of inherited wealth and Australia at the end of the 18th century inspired by Anthony Trollope, is published by Jonathan Cape, priced £17.99.

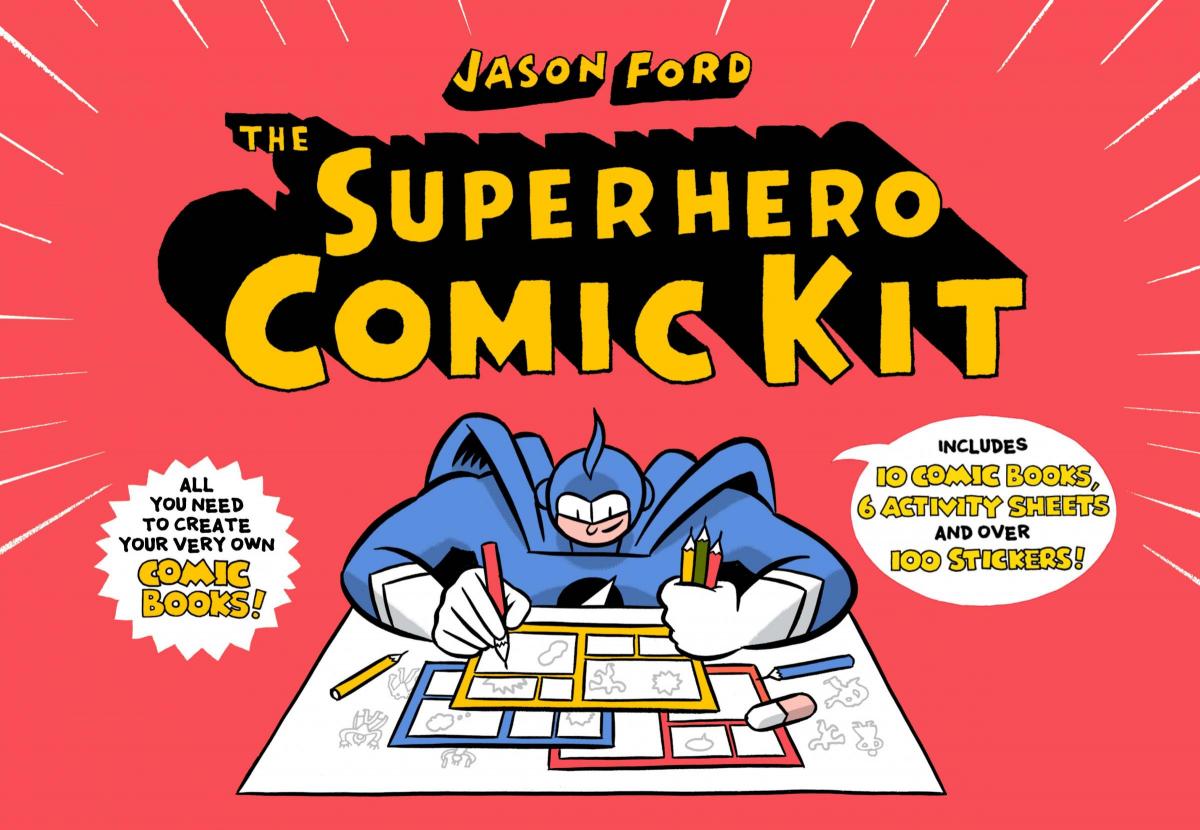

Jason Ford, creator of the Superhero Comic Kit

My introduction to comics came at an early age from watching Tom & Jerry cartoons. It had a profound effect on my young optic nerves and impressionable brain.

The opening titles of beautiful drop shadow lettering of the Fred Quimby-produced animation promised drama, hilarity and extreme physical slapstick, all executed in the glorious palate of Technicolour.

Comics seemed a natural extension of this world especially when I came across Herge’s Tintin and Uderzo & Goscinny’s Asterix the Gaul. The economy of line, the colours, the attention to detail, particularly the backgrounds, and the way narrative could be expanded or condensed, made the stories so compelling. They were like animated cartoons in book form, but very sophisticated.

As I hit my teens, the dynamic world of Marvel introduced itself via the fabulous skills of Jack Kirby who could convey speed, power, mass and intergalactic nebula when pencilling the adventures of the Fantastic Four or The Hulk.

My nascent interest coalesced in to wanting to become a cartoonist (at the time I didn’t know you could do something called “illustration”) and I headed off to the distracting world of art school, where my head was turned and I suddenly felt that having a love of comics was, well, a bit juvenile.

However, I realized that comics was where I drew my own inspiration and stylistic tics from, over and over again, in my subsequent years as an illustrator.

The cover of Jason Ford’s The Superhero Comic Kit (Laurence King Publishing, £12.95) bears the legend “All You Need to Create Your Very Own Comic Books!”. Inside there are stickers and superheroes and villains and lots of empty pages to fill with your own visions. Flicking through it, you will wish you were 12 years old again.

Why are you making commenting on The Herald only available to subscribers?

It should have been a safe space for informed debate, somewhere for readers to discuss issues around the biggest stories of the day, but all too often the below the line comments on most websites have become bogged down by off-topic discussions and abuse.

heraldscotland.com is tackling this problem by allowing only subscribers to comment.

We are doing this to improve the experience for our loyal readers and we believe it will reduce the ability of trolls and troublemakers, who occasionally find their way onto our site, to abuse our journalists and readers. We also hope it will help the comments section fulfil its promise as a part of Scotland's conversation with itself.

We are lucky at The Herald. We are read by an informed, educated readership who can add their knowledge and insights to our stories.

That is invaluable.

We are making the subscriber-only change to support our valued readers, who tell us they don't want the site cluttered up with irrelevant comments, untruths and abuse.

In the past, the journalist’s job was to collect and distribute information to the audience. Technology means that readers can shape a discussion. We look forward to hearing from you on heraldscotland.com

Comments & Moderation

Readers’ comments: You are personally liable for the content of any comments you upload to this website, so please act responsibly. We do not pre-moderate or monitor readers’ comments appearing on our websites, but we do post-moderate in response to complaints we receive or otherwise when a potential problem comes to our attention. You can make a complaint by using the ‘report this post’ link . We may then apply our discretion under the user terms to amend or delete comments.

Post moderation is undertaken full-time 9am-6pm on weekdays, and on a part-time basis outwith those hours.

Read the rules here