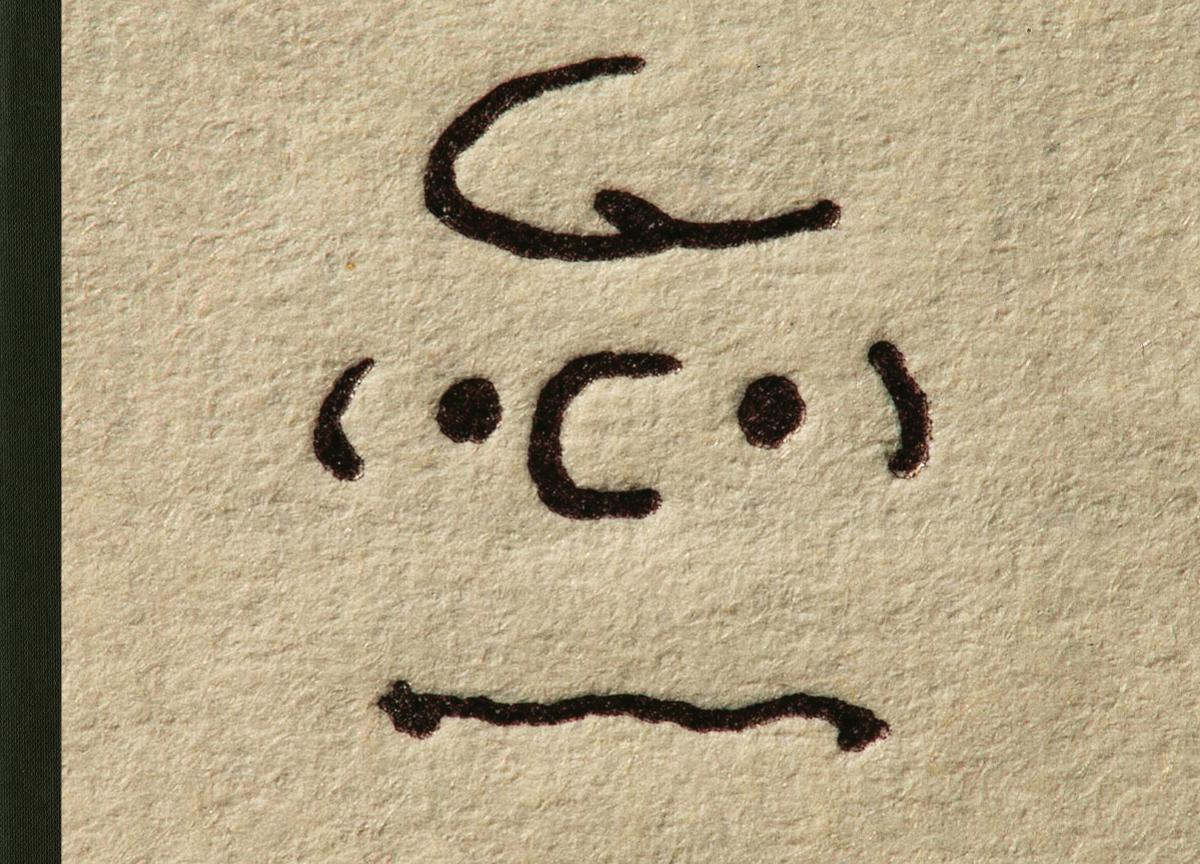

The cover is rough stock, tactile. You can follow the lines with your fingers, feel the indentations. The bulbous squiggle that stands in for a nose, the deep black dots of eyes, the wavering line that does double duty as a mouth and as an emotional state. (Nervous? Anxious? Convinced that someone is going to pull the ball away from him at the last moment?)

In all, it’s five lines and two dots, but that’s all you need. You only need five lines and two dots to know what you are looking at. You only need five lines and two dots to recognise the character and recognise that’s character’s very being. We are looking at lines and dots and we are seeing a lifetime of cartooning reduced and reduced and reduced to pure design. We are looking at Charlie Brown.

Or, if you like, we are looking at Only What’s Necessary. A statement of fact and the title of a new book subtitled Charles M. Schulz and the Art of Peanuts. Drawn from items in the Charles M Schulz Museum, it is a gather-up of Schulz’s original drawings, and a chance to see the development of the art and the brand. The original workings and then the by-products of Schulz’s comic strip.

Schulz started cartooning after the war and created a cartoon Li’l Folks which ran for three years before creating Peanuts. It would run for 50 years, from 1950 to 2000. Only What’s Necessary is a sideway glance at those five decades.

The book’s text, art direction and design has been masterminded by book designer and pop culture fetishist Chip Kidd. He spoke to Graphic Content about the project and about what Peanuts has meant to him over the years:

What can we expect from Only What’s Necessary?

Chip Kidd: Basically the museum in Santa Rosa came into being, I believe, in 2002 and for the past 13 or so years they have been amassing an archive there. And that in a large part is what the book is.

I’ve been talking with my editor at Abrams for many years about doing a Schulz “original art book” and that’s essentially what it is. But when we got to the archive and really went through it we found a lot of really interesting previously unpublished pieces; sketches that spanned the entire career from his original drawings of his dog that he sent to Ripley’s Believe It or Not and was published when he was 13 all the way up to the end with strips that he had drawn but decided that he didn’t want published.

Certainly fans have seen that dog cartoon republished many times but to see the original drawing and really get up close to it and see where his talent was at that age you get a much better impression.

I think there were certain strips, especially at the beginning, that he did not want reprinted because he did not think they were his best work. But I think, in retrospect, he is such a seminal figure of the second half of the twentieth century that it is essential that there is a record of everything you can make a record of. A couple of the things that we found and published are kind of the missing links, if you will, from the Li’l Folks strip to Peanuts itself. And as a fan I thought that was the most interesting stuff.

Would you separate the artist from the cartoonist?

I wouldn’t separate the artist from the cartoonist. I’m thinking out loud here, but would you separate Picasso the painter from Picasso the artist? That was the medium that he used to communicate to the world. Now it may not be the best analogy because Picasso was also a sculptor and what have you, but Schulz was definitely a cartoonist and that’s what he always wanted to be.

He used the medium of the comic strip to communicate to, eventually, the world. The readership of the strip is really a global phenomenon and that continues to this day. He was able to emotionally connect to his audience in a way that I would say that no other cartoonist has been able to achieve.

You could make an argument for Disney, but the huge difference is that very early on in Disney’s career he simply did not draw any more. It grew and grew and he wanted to make this huge creative empire, whereas with Schulz it was the opposite. He never wanted anyone else to draw the strip and nobody else ever did.

For 50 years straight he completely controlled what we know of as Peanuts. Now in terms of the licencing and the television shows and what have you he would relinquish creative control. He compartmentalised the two. There was the strip which he had total control over and then there was everything else.

For the record in terms of the television shows, the first two, the Christmas and the Halloween shows, he did have complete creative control over those.

What did you learn from looking at the original art?

You get a better understanding that a human being had to draw all this. And in his case he did everything. He would sketch out ideas and then would do the dialogue first. And then, once he got to a point where he was pleased with that, he would do the figures. And that was pretty much unchanged in the 50-year history of the strip.

But what did change was the evolution of the characters. Through the fifties they did grow up a little, but by the end of the fifties that was it. They would not be growing up any more.

All sorts of critics have weighed in, notably Italo Calvino, saying that they really aren’t children but adults with adult concerns and neuroses. That’s not for me to say and that’s not what this book is. It’s very much an art book.

But I think with any artist or cartoonist there is no experience quite like looking at the original, whether that’s a painting at the Metropolitan Museum of Art or comic book art or anything else. It’s almost always a revelation.

What are your own childhood memories of reading Peanuts?

I read it in the newspaper like everybody else but also, and to me more importantly, in first or second grade –we’re talking the early 1970s - in the reprint collections. That meant you’d read them in a large chunk rather than just one strip a day and it was my first real experience of feeling like I’d read an entire book in maybe one sitting.

There was something about it that felt so substantial as compared to reading an issue of a comic book. “This is a distinct body of work.” I wouldn’t have expressed it quite that way, but I remember feeling that way.

Sometimes he would sequence things that would play out over a week or several weeks and that’s when you had some kind of continuous narrative. Probably the most notable in the 1970s was when Charlie Brown developed a rash on his head that looked like a baseball. I only found out when doing this book it was all a reference to when he was in the army.

When he was recruited Schulz did his basic training in Kentucky and then he was shipped off to Europe for the end of the Second World War. And that is when he finally felt like a leader rather than a loser basically. By the end of that experience he had young GIs coming up to him and asking him for his guidance on this or that, or they wanted his advice and that was a revelation to him.

So that sequence of Charlie Brown when he became “Mr Sack” is really about his experience in the army.

Is there a danger with Peanuts that the strip gets lost under the toys and spin-offs?

I think as long as the strip collections remain in print I think they’ll find an audience with parents passing them on to their kids. It certainly transcends generations. It ran for 50 years. I don’t know many pop culture phenomena that cool disaffected teens like and their parents do too. It’s really quite extraordinary.

And then there’s a film coming, Peanuts the Movie. But it’s computer-generated imagery. Is that the way to go?

Since the late sixties there have been all these other media competing for the attention of the Peanuts fans and I don’t think that’s a bad thing that that’s continuing. Schulz’s son Craig co-wrote the screenplay and I think they’re trying to be as faithful to what the strip was through the medium of this movie and reintroduce it to a new generation and I think that’s a good thing.

Finally, which Peanuts character do you see yourself in most?

I would say Linus and especially when he got glasses. Either consciously or subconsciously my glasses look exactly the same.

Only What's Necessary: Charles M. Schulz and the Art of Peanuts is published Abrams ComicArts, priced £25

Why are you making commenting on The Herald only available to subscribers?

It should have been a safe space for informed debate, somewhere for readers to discuss issues around the biggest stories of the day, but all too often the below the line comments on most websites have become bogged down by off-topic discussions and abuse.

heraldscotland.com is tackling this problem by allowing only subscribers to comment.

We are doing this to improve the experience for our loyal readers and we believe it will reduce the ability of trolls and troublemakers, who occasionally find their way onto our site, to abuse our journalists and readers. We also hope it will help the comments section fulfil its promise as a part of Scotland's conversation with itself.

We are lucky at The Herald. We are read by an informed, educated readership who can add their knowledge and insights to our stories.

That is invaluable.

We are making the subscriber-only change to support our valued readers, who tell us they don't want the site cluttered up with irrelevant comments, untruths and abuse.

In the past, the journalist’s job was to collect and distribute information to the audience. Technology means that readers can shape a discussion. We look forward to hearing from you on heraldscotland.com

Comments & Moderation

Readers’ comments: You are personally liable for the content of any comments you upload to this website, so please act responsibly. We do not pre-moderate or monitor readers’ comments appearing on our websites, but we do post-moderate in response to complaints we receive or otherwise when a potential problem comes to our attention. You can make a complaint by using the ‘report this post’ link . We may then apply our discretion under the user terms to amend or delete comments.

Post moderation is undertaken full-time 9am-6pm on weekdays, and on a part-time basis outwith those hours.

Read the rules here