ELIZABETH lived on the streets. Her bed was wherever she could lie down in comparative safety. For over a year her nights were spent curled up on top of a sack inside a flimsy street kiosk.

“I used to pray before sleeping,” she tells me as we sit talking, our voices almost drowned out by the roar of the ubiquitous petrol generator that provides round-the-clock power in this, Africa’s most populous city where the electricity supply is erratic.

Sleeping rough anywhere is a terrifying experience. Here in the frenetic madness that is Lagos, where somewhere between 13 million and 18 million people live, sleeping on the streets doesn’t bear thinking about, especially for a young woman.

If darkness brought its own terrors then daytime was not much better for Elizabeth.

“I lived by begging, sometimes I would rub menthol on my eyes to make tears, so that passersby might give me a little money,” the teenager confesses.

Elizabeth lost her mother when she was six years old and never really knew her father who was from the neighbouring West African country of Benin.

Her parents gone she lived with an aunt who Elizabeth says harboured a terrible resentment for the young girl thrust into her life.

“My aunt was very harsh, ‘go and meet your dead mother’, she would often say to me,” Elizabeth recalls of those times that became so unpleasant she left to live on Lagos streets.

If it had not been for the intervention of a woman called Seriki Abosede, Elizabeth might have found herself trapped in a cycle of begging and the constant pull towards the nightmare of prostitution to which so many street girls in Lagos succumb in order to earn a few Nigerian Naira.

“I had no one to help me when I was young, I had to fend for myself, so I decided to give something back to help others, says Seriki.

That something was to take Elizabeth under her wing and offer her the chance of employment with Seriki’s small business ‘London Braids’ a hairdressing and braiding salon that she started up 12 years ago.

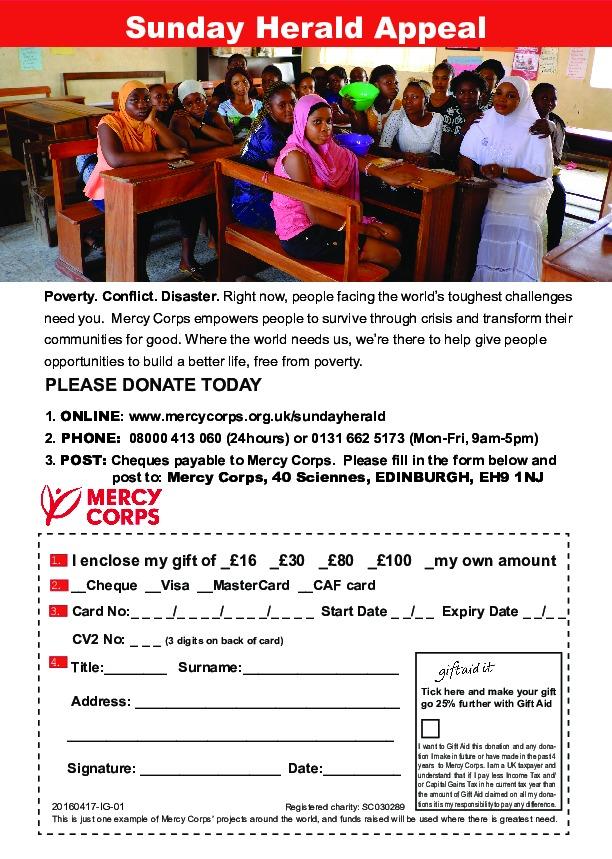

Today Seriki has some 18 employees, 10 of which including Elizabeth are part of a unique project that focuses on empowering out of school girls with the skills and resources they need to build a more stable future.

“She is always there for me,” says Elizabeth of Seriki as they stand arm-in-arm in the salon surrounded by other young women working on braiding wigs. Some have babies lashed to their back or toddlers running around at their feet

In Nigeria there is a desperate need for initiatives such as the one that took Elizabeth off the streets and into employment.

Of the 250 million adolescent girls in the world living in poverty, more than 14 million live in Nigeria. This is a country of stark contrasts and nowhere is this more apparent that in the lives of young women.

In Nigeria’s north women have born the brunt of the violence that has resulted from the insurgency by the Islamist terror group Boko Haram.

It was two years ago last week that 276 schoolgirls were abducted by Boko Haram, 15 of who appeared on a “proof of life” video released last week by the terrorists. Since the kidnapping of the schoolgirls, hundreds more women and girls have been abducted, imprisoned and forced into sexual slavery.

Girls who have been indoctrinated and drugged now account for three quarters of the suicide bombings that take place in north-eastern Nigeria. Tens of thousands more women have been displaced from their homes and struggle to make ends meet after losing husbands to Boko Haram’s killers.

In Lagos far from the ravages of that conflict young women also face immense challenges. Nigeria might be oil-enriched but that is only one side of the story.

This oil wealth in part accounts for its 15,700 millionaires and handful of billionaires, sixty per cent of which live in Lagos. But as with other African metropolises, Lagos has long nurtured an elite class only marginally inconvenienced by the squalor and poverty enveloping the city as a whole. On the city’s teeming streets on which there is some of the worst traffic congestion on the planet, it is not uncommon to see a special paramilitary police unit.

This unit goes by the colourful name ‘Kick Against Indiscipline Brigade’ (KAI) and its job involves everything from cracking down on illegal petty traders to controlling the city’s notorious street gangs in some of the poorest neighbourhoods.

It is in these same impoverished neighbourhoods that many of Lagos’s most vulnerable citizens are to be found among them young girls who for a variety of reasons have dropped out of school and find themselves without work.

“Sometimes you find a girl dropping out of school for as little as a $5 levy, and that’s it for her,” says Rabi Sani, Director of Gender Programmes with the humanitarian agency Mercy Corps.

“What we want to do is help them start up small businesses, acquire some skills and be able to start up on their own because data has shown that they contribute to household income, even at this level very significantly,” says Rabi.

It was this scheme that brought Elizabeth into Seriki’s braiding salon, where she now works. When not at the salon or out attending customers in their home, Elizabeth attends group meetings where other girls in the programme contribute a small amount of their money to a collective pool of savings. Each of the girls can borrow from the pool to buy basic supplies and tools for their own entrepreneurial activities.

Known by the acronym Engine (Educating Nigerian Girls in New Enterprises) some 3,800 girls have now gone through the scheme with a target of 18,000 to be reached. Engine is a deceptively simple but effective means of giving girls from the poorest backgrounds a chance they might otherwise never have.

Too often girls like this face traditional, patriarchal and cultural barriers that limit their involvement in educational and economic activities. This after all is a country with the largest number of children out of school in the world, some 10.5 million.

For girls the disadvantages start early. Only 45 per cent of secondary-aged girls attend school and only 1 per cent of teenage girls are expected to re-enroll if they have been out. Add to this the fact that by the time they reach the age of 18 then 43 per cent will be married and 29 per cent will have had at least one baby, and the limitations on their individual empowerment becomes obvious.

Over and again such girls are confronted with high rates of gender-based violence, unwanted pregnancy, limited income-generating opportunities and restricted access to appropriate health information and services.

Like Elizabeth, Wasilat is in her late teens and joined the ENGINE scheme last year. A single mother, she was given an apprenticeship with a small tailoring and dressmaking business through the scheme. Since then the 28,000 Naira around £100 she has saved enabled Wasilat to buy a sewing machine with which he has started to do work for her own customers.

Such sums might seem tiny but as is often the case with those who live constantly in the shadow of poverty, they can make all the difference between survival and a potentially disastrous fate.

“The scheme has made all the difference,” says Wasilat’s older brother Taofiq.

“It has helped prevent some poorer girls from this community being forced into prostitution and the sex trade,” he explains as we sit in the family’s dilapidated home in a rundown neighbourhood of Lagos. Out on the street runs an open sewer and in the small patch of land outside the house are a few graves of grandparents and relatives, reminders that for some families generations are often locked into crushing poverty for years if not a lifetime.

“Since she dropped out of school, she was always out on the streets but now she is back in the home, and I thank Mercy Corps and the project for that,” says Wasilat’s mother as her daughter sits working on a blouse on her sewing machine.

What does she hope for the future, I ask Wasilat?

“My dream is to have my own tailoring business and have other people working with me,” she replies with a quiet confidence.

Of the almost 4,000 girls who have gone through the scheme, many leave intent on becoming mentors and role models to other girls, and job creators for their communities.

"We started with very, very timid girls, girls that could barely look at a female to talk, girls that completely lacked self-esteem," says Mercy Corps Rabi Sani. "Over the two years, we've been able to see and interact with girls that have become much more confident, girls that have a clear vision of what they want to do. They are daring to dream bold dreams, that before now they couldn't even imagine. They are beginning to see a whole world of possibility."

Just before leaving Lagos I was to meet one other girl who was a beneficiary of the ENGINE project. Abimbola dropped out of school when she was 14 but heard of the scheme through friends who told here she might be able to learn what she really wanted to do. Today she has three months remaining of her apprenticeship with a catering firm and has saved 15,000 Naira. She has no intentions of stopping there however and intends returning to school to pick up on the education she missed out on.

“I would like to be a lawyer, I like mediation,” she tells me, explaining that she learned some of these mediation skills through the support group that she attends where along with the other girls she is mentored in basic business, financial and life skills training.

For all the girls on the project the role of what is called a ‘gatekeeper’ is crucial. In Elizabeth’s case that gatekeeper was her friend and carer, Seriki, in Wasilat’s experience it was her wider family. For Abimbola it was the support of her friends and father who acted as gatekeepers encouraging her to enter the scheme.

“Anything that makes my daughter’s life better, I am for,” Abimbola’s father, Olusegun says. “I put my heart on it.”

Over the course of my time in Nigeria and in writing this series of articles I have met women who are doing extraordinary things in the face of the most dangerous and difficult obstacles and challenges. From those who have survived the horrors of Boko Haram terrorism to those who have shown a similar resourcefulness and courage in the face of often crushing poverty. All are to be applauded and all deserve our support.

Why are you making commenting on The Herald only available to subscribers?

It should have been a safe space for informed debate, somewhere for readers to discuss issues around the biggest stories of the day, but all too often the below the line comments on most websites have become bogged down by off-topic discussions and abuse.

heraldscotland.com is tackling this problem by allowing only subscribers to comment.

We are doing this to improve the experience for our loyal readers and we believe it will reduce the ability of trolls and troublemakers, who occasionally find their way onto our site, to abuse our journalists and readers. We also hope it will help the comments section fulfil its promise as a part of Scotland's conversation with itself.

We are lucky at The Herald. We are read by an informed, educated readership who can add their knowledge and insights to our stories.

That is invaluable.

We are making the subscriber-only change to support our valued readers, who tell us they don't want the site cluttered up with irrelevant comments, untruths and abuse.

In the past, the journalist’s job was to collect and distribute information to the audience. Technology means that readers can shape a discussion. We look forward to hearing from you on heraldscotland.com

Comments & Moderation

Readers’ comments: You are personally liable for the content of any comments you upload to this website, so please act responsibly. We do not pre-moderate or monitor readers’ comments appearing on our websites, but we do post-moderate in response to complaints we receive or otherwise when a potential problem comes to our attention. You can make a complaint by using the ‘report this post’ link . We may then apply our discretion under the user terms to amend or delete comments.

Post moderation is undertaken full-time 9am-6pm on weekdays, and on a part-time basis outwith those hours.

Read the rules here