THE family of a man who took his own life after serving nine years in jail for a murder he insisted he did not commit have failed in a bid to clear his name...despite evidence another man had boasted he was the real killer.

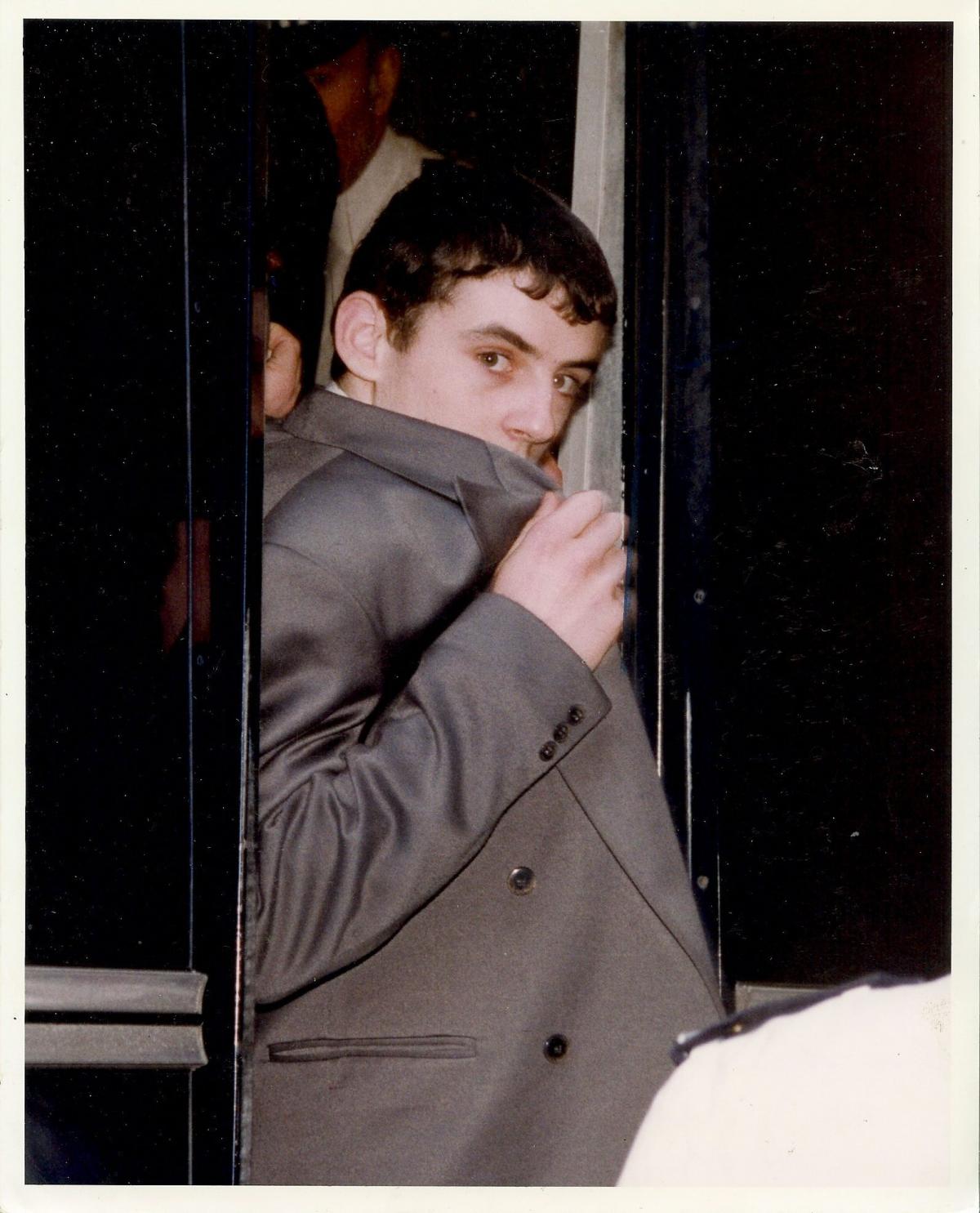

John McIntosh, was 17 when he was sentenced to life for stabbing Stephen McDermott, 27, outside his home in Nitshill, Glasgow during a night of violence in February, 1992.

He is thought to have taken his own life at home in 2014 after he spent nine years in prison for a drug-fuelled killing of taxi driver Stephen McDermott, 27, in February 1992.

He had been fighting in vain to clear his name after another man claimed to be the killer.

The former shipping container industry worker, who died aged 38, told his family he "felt let down by the legal system" and repeated this to Twitter followers hours before he took his life.

Relatives took the case to the Scottish Criminal Cases Review Commission in an attempt to get a posthumous pardon with support from the Glasgow-based Miscarriages of Justice Organisation which said McIntosh's death was a scandal.

But the SCRC has now decided not to refer the case back to the High Court saying they do not believe a miscarriage of justice has taken place, backing the court's view, and saying they were not persuaded that the additional evidence was "significant".

The family have said they will continue to fight for a posthumous pardon.

His sister, Dorothy said: "Yes if we have another avenue then we will pursue that."

Evidence revealed co-accused Stephen Harkins had bragged about being the real murderer before and after the trial was deemed inadmissable by appeal judges in 1994.

At the original trial, the jury convicted McIntosh of murder by a majority verdict, and, also by a majority, found the murder charge against Harkins - then 22 - not proven.

By the time of an appeal six years later there were seven affidavits, including one from prison officer William Blake, saying that Harkins had boasted about being the real murderer.

But McIntosh's family were stunned when appeal judge Lord Coulsfield in 2000, while accepting the evidence may have led a jury to accept Harkins did claim on several occasions that he had committed the murder, he felt it was not of such significance to show a miscarriage of justice had occurred. Lord Coulsfield then dismissed the appeal.

Now in a statement to the family, the SCCRC said that Harkins was "fireproof" with regards to the offence as he could not be re-prosecuted for the murder and could not be prosecuted for perjury.

The SCCRC said: "In other words he was free to make any admissions he wished to make about that offence without fear of being punished for that offence or for an offence or for an offence relating to his actions at his trial for that offence."

The SCCRC said the appeal court noted he was a "boastful character" and that as soon as it appeared there "might be adverse consequences to him... he appeared to disassociate himself from his admissions".

The commission accepted the issue it was required to address was whether the post-trial admissions by Harkins were capable of being regarded as credible and reliable by a reasonable jury, and whether it had a material bearing on, or a material part to play in, the consideration by the original trial jury.

The SCCRC noted that the court did observe that the evidence "could not simply be dismissed as incredible and unreliable", and there was "an argument that the court concluded that the evidence was, at the very least, capable of being regarded as credible and reliable by a reasonable jury".

But the SCCRC added: "In any event, as the critical issue at trial was whether it was McIntosh or Harkins who stabbed the deceased, the ultimate question was whether the additional evidence is likely to have had a material bearing on, or a material part to play in, a reasonable jury's determination as regards which accused stabbed the decease.

"The commission noted the evidence against the accused; it noted the comments the trial judge made concerning 'the addition of any further material evidence'. Within that context, and having regard to the particular nature of the additional evidence under discussion, the commission was not persuaded that the additional evidence was significant".

The SCCRC said it was not disputed that Harkins at a first appeal declined to give a statement to the Crown and that he refused at both appeals to co-operate with those representing McIntosh.

The commission concluded: "Accordingly the commission does not believe that there may have been a miscarriage of justice in this case."

Four years ago, at the age of 37, and with a 21-year-old son, McIntosh, then free from prison, told sister paper The Herald he had tried to kill himself three times as a result of "the torment of what happened" and pledged to leave "no stone unturned" in fighting the case, including taking a lie detector test if necessary to prove his innocence.

He and his co-accused blamed each other for the murder, with both said to have been "full of jellies" – a reference to the drug temazepam – at the time.

The judge, Lord Prosser, told the jury during the 1993 trial that there appeared to be substantial evidence against Harkins, who had already used his knife on another man that night. Only one person had stabbed McDermott.

But there was also blood on a distinctive jacket said to have been worn by McIntosh.

Subsequent sworn statements that Harkins had admitted sole responsibility for the murder before and after the trial were deemed "hearsay evidence".

Four judges headed by Lord Ross, the Lord Justice Clerk, decided in an original appeal in 1994 that it would be against public policy to relax the rule against hearsay, even if that meant ruling out evidence of genuine confessions.

They pointed to the danger that accomplices of the accused would try to get him off by giving concocted evidence of false or non-existent confessions by third parties.

However, Lord McCluskey said the hearsay rule should be relaxed to allow someone in McIntosh's position to lead new evidence at a retrial. He said: ''In relation to the public interest aspect I note that [McIntosh] has been convicted of the most serious charge known to our criminal law. It appears from the report of the trial judge that he considered that, on the evidence, Harkins was more likely to be convicted of the murder...Against that background I think it is possible to see the importance of a jury having before it evidence as to Harkins's alleged admissions of sole responsibility.''

In December, 1997, then Scottish Secretary Donald Dewar referred the case to the Court of Appeal in a landmark ruling that resulted in the statements being considered. New laws allowed evidence that came to light after a conviction to be admitted as grounds for appeal.

That evidence included a statement from William Blake, a prison officer in Greenock Prison, who said Harkins told him McIntosh was serving life for a murder he had not committed.

Court papers say: "Blake had not been interested because it was raining and they were trying to get through the grill gate, but Harkins went on and said, 'I know who did it – I did it'."

It did not occur to Blake to tell senior officers immediately and he refused to give an affidavit at first as he feared harm would come to him, court papers said. He eventually made a statement after Harkins died in January 1999.

Other evidence was provided by two convicted murderers and a robber serving eight years.

In April 2000, Lord Coulsfield while dismissing the appeal, questioned the admissions, saying Harkins was regarded, by other prisoners and by prison officers, as "boastful, a nuisance and a person who was in the habit of indulging in bravado".

McIntosh said after the failed appeal: "It hurts me that the Court of Appeal had the chance to put things right but chose to brush me off by simply saying Harkins was just boasting. It was just the easy way out for the court."

While in prison he says he wrote to the murder victim's parents to apologise for being involved "in such a horrific case" but claimed he did not kill their son. There was no reply.

A year after Lord Coulsfield's 2000 appeal ruling, McIntosh was released on "interim liberation".

Why are you making commenting on The Herald only available to subscribers?

It should have been a safe space for informed debate, somewhere for readers to discuss issues around the biggest stories of the day, but all too often the below the line comments on most websites have become bogged down by off-topic discussions and abuse.

heraldscotland.com is tackling this problem by allowing only subscribers to comment.

We are doing this to improve the experience for our loyal readers and we believe it will reduce the ability of trolls and troublemakers, who occasionally find their way onto our site, to abuse our journalists and readers. We also hope it will help the comments section fulfil its promise as a part of Scotland's conversation with itself.

We are lucky at The Herald. We are read by an informed, educated readership who can add their knowledge and insights to our stories.

That is invaluable.

We are making the subscriber-only change to support our valued readers, who tell us they don't want the site cluttered up with irrelevant comments, untruths and abuse.

In the past, the journalist’s job was to collect and distribute information to the audience. Technology means that readers can shape a discussion. We look forward to hearing from you on heraldscotland.com

Comments & Moderation

Readers’ comments: You are personally liable for the content of any comments you upload to this website, so please act responsibly. We do not pre-moderate or monitor readers’ comments appearing on our websites, but we do post-moderate in response to complaints we receive or otherwise when a potential problem comes to our attention. You can make a complaint by using the ‘report this post’ link . We may then apply our discretion under the user terms to amend or delete comments.

Post moderation is undertaken full-time 9am-6pm on weekdays, and on a part-time basis outwith those hours.

Read the rules here