AFTER nearly two decades in Denmark, Stewart Trout is still being told he is “the right kind of foreigner”. After Brexit, says the 43-year-old Scot, 43, this is not longer reassuring.

Some Danes, just like a few of their neighbours across the North Sea, are lurching to the xenophobic right. One new Danish party has been distributing cans of what it calls “asylum spray”, supposedly to protect women from Muslim rapists. Mainstream politicians have responded with ever tougher crackdowns on migrants.

So Mr Trout, his status as an EU citizen now cast in to doubt by the June Brexit vote, is now anxious. “My ultimate goal is to be a Danish national but that is not being made easy,” said the father of four Danish children. “There are new right-wing anti-migrant parties – even the Socialists are hard on immigration – and I am now really worried about how negotiations on free movement will go after the UK leaves.”

As a Western European who has learned Danish, Mr Trout, a kindergarten worker currently between jobs, is not the kind of migrant who suffers most from the current backlash. “I am always being told I am the right kind of foreigner,” he explained, before adding it was “quite conceivable” non-EU British citizens could fall foul of bureaucracy inspired by fear of migrants from further afield.

There was no such angst for Mr Trout, who is originally from Helensburgh, when he first came to Denmark, in January 1997. Fresh out of the army and working as security guard, Celtic fan Mr Trout had met a young Dane who was working as an au pair for the then Rangers star Brian Laudrup. She left for Copenhagen. Her footballer employer bought a Mr Trout an open-return ticket to visit her.

“I had £20 in my pocket when I got off the plane,” he said. “I have never wanted to go back. I love the way of life here and I am sorry to say it is much better than in Britain, which just gets more and more dismal every time I visit.”

Mr Trout, who lives in Ringsted in the heart of the island of Zealand, hopes his fellow Scots get another chance to vote for independence so he can keep his EU citizenship.

“Some of the other Scots have been talking. Our worst-case scenario would be to go back to the UK. That would be terrible.”

Family cannot be tied down

There are migrant families who leave one home to find another. And then there are those who just have more than one home. The Johnsons are among the latter.

Nick, a Tory MSP in the early years of the Scottish Parliament, now lives in Barcelona with his Catalan wife Anna.

Their Scottish-born but Spanish-educated son Adam, meanwhile, stays in Edinburgh with his Catalan girlfriend Paula. On paper, Nick is a migrant and so is Paula. Scroll back a few years and the same could be said of Anna, who used to live in Scotland, and Adam, who was brought up in Spain.

Anger in Spanish media

Freedom of movement across the European Union, for the Johnsons, is not some dry academic theory. It is a way of life. And one that Brexit may put at risk for the thousands of Scottish families whose members feel at home in different parts of the EU.

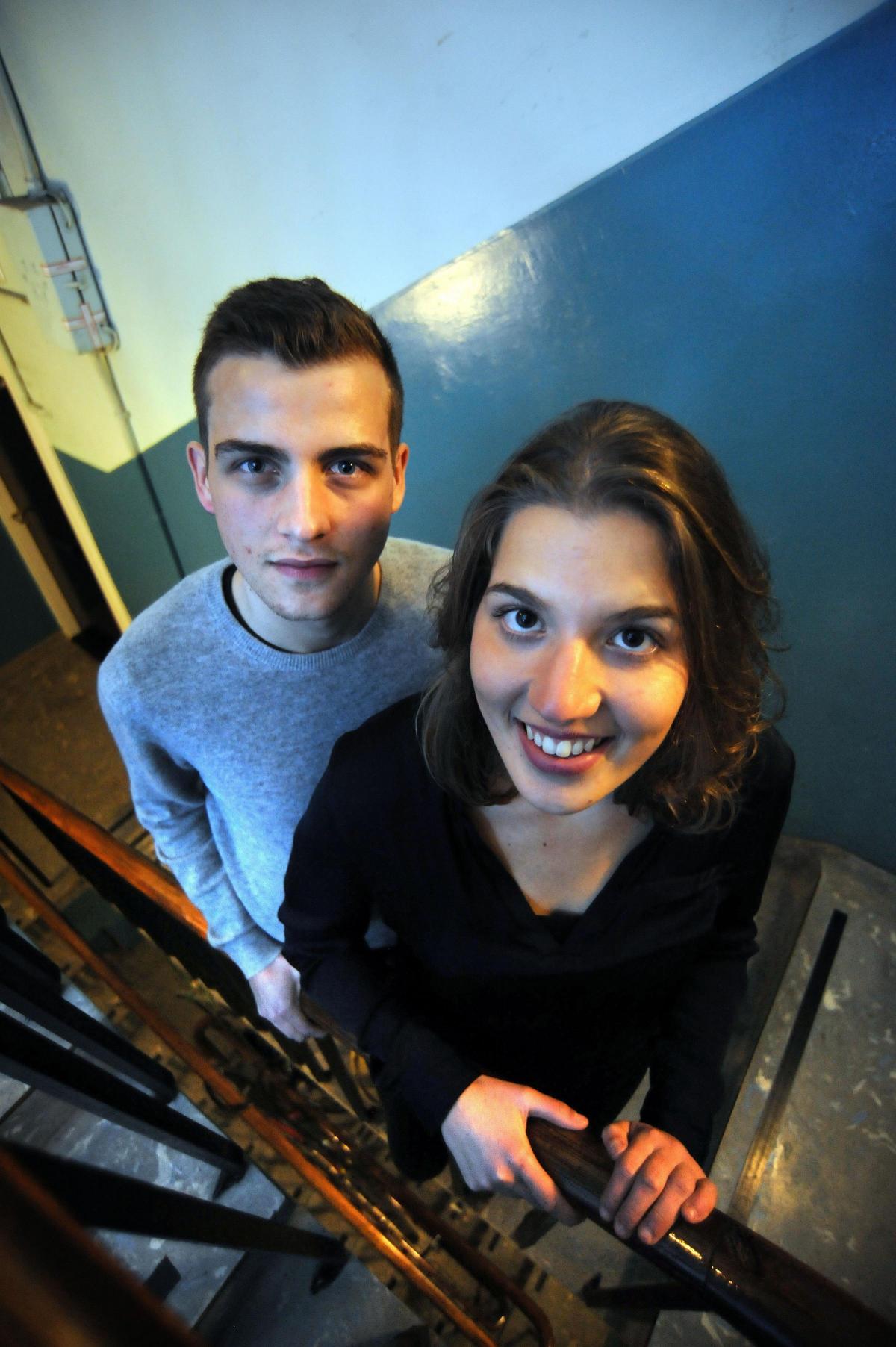

“These are just things we have taken for granted for so long,” says Adam, 22, a newly graduated product designer. “Paula, for example, is a nurse who has taken advantage of the free movement.”

The UK Government has signalled it will not deport EU nationals currently living in the UK. And there has been little sign of Spain – which is home to not quite counted hundreds of thousands of British citizens – would respond tit-for-tat if it did.

But families like the Johnsons are still nervous. Nick, now retired, explained: “I don’t think Spain will throw me out After all, I am not doing any harm here and I am contributing to the local economy. But what would concern me, as someone who is 68, is if Spain said we were no longer entitled to medical services.”

There have been rumblings of discontent in the Spanish press about Britons – officially there are 310,000 of them but estimates suggest there are many, many more – using scarce health resources. Many expats are elderly and vulnerable. Some, having never learned Spanish, have become socially and politically isolated and already struggle to access services.

Nick blames his own old party for holding the Brexit referendum in the first place and putting such “expats” – as British immigrants often style themselves – at risk.

A convert to the cause of Scottish independence, he now hopes a Scottish sovereign state can protect his EU rights. Back in Edinburgh, like many Euro-Scots”, his son Adam agrees. “I don’t see how Scotland can keep all the advantages of EU memberships while staying in the UK,” he said.

“But if we do stay in the UK, any kind of movement freedom would be welcome to ensure Scottish people can hold on to as many of the rights they voted for as possible.”

Why are you making commenting on The Herald only available to subscribers?

It should have been a safe space for informed debate, somewhere for readers to discuss issues around the biggest stories of the day, but all too often the below the line comments on most websites have become bogged down by off-topic discussions and abuse.

heraldscotland.com is tackling this problem by allowing only subscribers to comment.

We are doing this to improve the experience for our loyal readers and we believe it will reduce the ability of trolls and troublemakers, who occasionally find their way onto our site, to abuse our journalists and readers. We also hope it will help the comments section fulfil its promise as a part of Scotland's conversation with itself.

We are lucky at The Herald. We are read by an informed, educated readership who can add their knowledge and insights to our stories.

That is invaluable.

We are making the subscriber-only change to support our valued readers, who tell us they don't want the site cluttered up with irrelevant comments, untruths and abuse.

In the past, the journalist’s job was to collect and distribute information to the audience. Technology means that readers can shape a discussion. We look forward to hearing from you on heraldscotland.com

Comments & Moderation

Readers’ comments: You are personally liable for the content of any comments you upload to this website, so please act responsibly. We do not pre-moderate or monitor readers’ comments appearing on our websites, but we do post-moderate in response to complaints we receive or otherwise when a potential problem comes to our attention. You can make a complaint by using the ‘report this post’ link . We may then apply our discretion under the user terms to amend or delete comments.

Post moderation is undertaken full-time 9am-6pm on weekdays, and on a part-time basis outwith those hours.

Read the rules here