SARAH Trevelyan is the woman I went to prison for. Well, technically it was the prison car park, and not the prison itself. But I should explain.

It was a dank, dark morning in January 1980, with snow on the hills. The whole of the Glasgow media was scrambled for the biggest story in Scotland – convicted killer Jimmy Boyle, a man who had slashed and fought through most of his short life, who had been an angry, violent prisoner, and who now appeared rehabilitated in the experimental Special Unit at Barlinnie Prison, was marrying young, public-schooled English psychiatrist Sarah Trevelyan, whom he had met behind bars.

Every news editor was salivating over the story while simultaneously fearing they might miss it. Teams of journalists were ready to spread out across the country. Someone had spotted the prosaic notice tacked on the board at Balfron Registry Office stating the wedding was going ahead there. But it might have been a decoy. So the Evening Times, where I then worked, was doing what every other newspaper was plotting. We had a reporter and a photographer in Balfron. A second team was outside Trevelyan's flat in Wilton Street, Glasgow, ready to follow her wherever she went.

And I was at Barlinnie, as you can't have a wedding without a groom, and we knew Boyle was in there. Not that we could get inside Barlinnie, a formidable, unwelcoming edifice in the east end of Glasgow. So we stood around outside, chatting, waiting for dawn to appear, staring in every vehicle trying to ascertain who was coming and going. There was the usual mordant humour of dyspeptic hacks. "What do you think he'd do to her if his tea was not on the table?" mused one. Not that journalists are the obvious people to give relationship advice.

Then a Volkswagen Beetle arrived. We knew it was the bride as it was accompanied by a dozen or so press cars. Imagine a speedy funeral procession but with an oddly-shaped car at the front instead of a hearse. Inside was a smiling Trevelyan driving her two female witnesses. The car went inside Barlinnie and reappeared shortly afterwards with Boyle on board in jeans and a blue cord jacket, accompanied by a bearded prison officer in a duffle coat. It was followed by a red Ford Escort full of plainclothes police officers, and the press circus quickly fell in behind.

And, sadly, I have to report that she was yet another woman who slipped away from me. You see I was in the office radio car being driven by Bobby the Driver. He was a former newspaper delivery van driver who had become editorial driver. Good for finding shops that sold hot rolls early in the morning, and pubs that kept odd opening hours, irritatingly he drew the line at going through red lights, which we would have to do to keep up.

"I'll lose my licence," he muttered. I begged him to let me drive but he was having none of it. I was the dog that barked as the caravan moved on to Balfron. We drove back to the office in silence. Don't think I even stopped for a hot roll or a pint.

My colleague "Gorgeous" George Phillips was at Balfron where the couple were indeed married, so the story was in the Evening Times that night, no thanks to me.

And that was the last I saw of Sarah Trevelyan until last week, when she opened the door of her mews house in a cobbled lane in Edinburgh, smiled and asked if I wanted a cup of tea. Thirty-seven years later and I could still recognise the eyes that had looked out of the window of the Beetle that morning. She is older, of course – we are both a lot older – and her dark hair now contains more grey. I explained about our fleeting Barlinnie connection. She laughed and said: "We finally meet."

We are meeting as Trevelyan has written a book about her life with Boyle, which was a marriage that lasted two decades, although they are now divorced, with Boyle living mainly in France, vowing never to return to Scotland. Trevelyan, although English, and brought up in Australia, feels far more at home in Scotland than Boyle ever did.

She never fell out of love with him, but his love for the finer things in life after prison – driving a Rolls-Royce, starting up a champagne importing business, wanting to wine and dine business contacts on the south coast of France – was not the life she wished for herself and their two children.

However the book, Freedom Found, which is a nod to Boyle's own book which brought him to a wider public, A Sense of Freedom, is not some pot-boiler dashed off by a wronged woman. Trevelyan is an intelligent, professional woman, who through visits to communities such as the new age Findhorn community and the Buddhist retreat Samye Ling went on her own personal journey, which took her into a life of spiritual discovery. Boyle felt he had done enough introspection in solitary confinement in the cells of Inverness and did not join her.

But first we should remind ourselves of Boyle. He was a criminal enforcer in Glasgow, ready with a knife and fists, who police had tried to pin two murders on before he was found guilty in 1967 for the murder of fellow gangster William “Babs” Rooney, and sentenced to life imprisonment with a minimum 15-year sentence. He always argued his innocence, but was unwilling to name the actual killer.

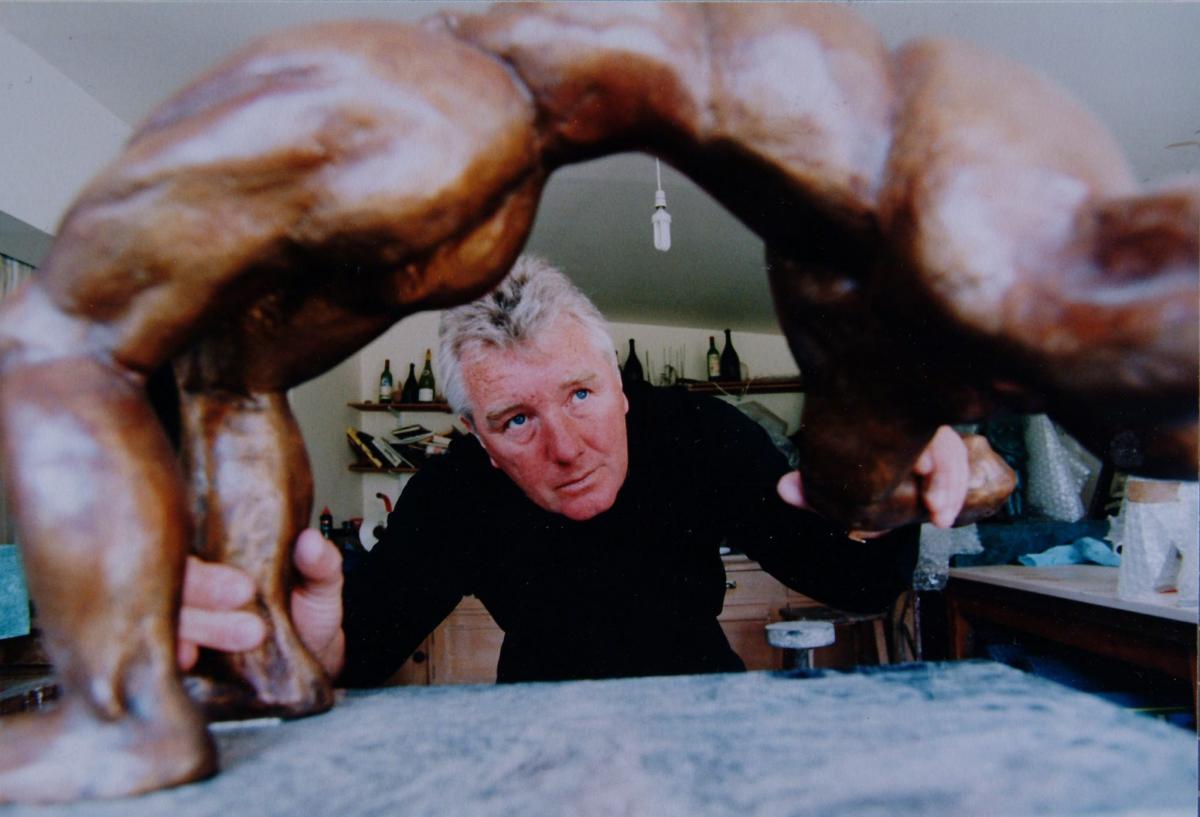

In jail he was a troublesome prisoner, until finally he was transferred to the Special Unit at Barlinnie which was an experimental scheme to give selected prisoners a huge amount of freedom to talk about their problems and explore other interests. Boyle became an artist and sculptor of some renown. The Special Unit is no more, but looking back, it is clear that it saved his life.

Then appeared Trevelyan, who was working in Scotland as a psychiatrist. Many people assumed she had met Boyle through her work, but it was not that simple. On a whim she bought his book at Inverness railway station to give her something to read on the train, and she was so taken with it that she wrote to him, asking to see him.

What the press did not know at the time, and which would have sent us even more apoplectic, is that Trevelyan had already been a regular visitor to an even more notorious convicted killer, Moors murderer Myra Hindley. She had gone to see Hindley with her father, James Trevelyan, secretary of the British Board of Film Censors, who was an advocate of prison reform.

“Dad was a very compassionate, humane man. He felt it would be good for Myra to meet someone more of her own age," says Trevelyan. "It was my first experience of Holloway Prison. It was intimidating. But people don’t match the headlines. Myra was dark-haired at that time, smoked heavily, and spoke in a very quiet voice. She was well educated and well informed of events around her."

But Myra Hindley! She anticipates my questions about Hindley’s wrongdoings and merely says, “We didn’t touch upon the past. I didn’t see that as my role.”

It was the same with Boyle, and his previous violence. “I tend to be in the moment with people I meet,” she says. “I don’t dwell on the past.

“Jimmy was warm hearted and with a lot of integrity and a lot of personal courage. I had to put this together with the fact he had been involved in gangland violence, but I met the Jimmy who he was then, and I didn’t dwell on the past.”

But Jimmy Boyle! She again anticipates my next question. “I never ever felt unsafe with Jimmy, and I never had any worries that violence would explode around me.” But she was naive, surely. She agrees, but qualifies it. “To me naivety is innocence, and innocence can be a positive quality.”

As she describes that first meeting in her book: “I was escorted upstairs to meet Jimmy in his cell. I had imagined meeting him in some kind of institutional setting like a hostel. I was completely unprepared to be invited into his cell, which was attractively decorated with green floral print William Morris wallpaper. Matching curtains framed a small high-up barred window. Shelves containing books and other personal items lined one of the walls.

“Jimmy, dressed in his denim dungarees, welcomed me standing beside his bed. He invited me to sit down on it, next to a table set for lunch. He had prepared what he called a Gorbals salad, along with a freshly baked loaf of bread he had made himself.

“I was delighted to be offered such a healthy spread. His face was fresh and alive. He was physically smaller than I had expected, but his compact physique was bursting with physical strength and energy. He spoke rapidly in a strong Glasgow accent. I was swept away on the stream of his words, and it seemed we instantly connected. Despite the differences in our backgrounds and circumstances, we understood each other.”

Romance blossomed alongside Boyle's artistic creativity. It could in the Special Unit, where cells were left unlocked and prisoners and visitors were given a great deal of freedom. It gave them a chance to become intimately involved with each other in a way that would not happen in the normal prison system. Not everyone was happy with such freedom for prisoners. Where was the punishment? But as Trevelyan argues, taking someone's freedom away is punishment enough, and more should be done to help them face life after prison.

They wanted to marry, so Boyle applied for permission and a date was set. I was re-reading The Herald’s coverage of the day where the front page intro was: “Psychiatrist Sarah Trevelyan spent the first night of her ‘honeymoon’ alone in her £16,000 flat in Glasgow's west end only hours after marrying murderer James Boyle yesterday.” That made me smile. First The Herald couldn’t stop itself from mentioning west end house prices, and of course Jimmy was called James as that was his proper name.

Initially the marriage, when Boyle was finally released, was eventful. He left prison in November, 1982, and the couple helped set up the Gateway Exchange in Edinburgh to help those on the edge of society through the arts. Billy Connolly officially opened it.

But many people wanted a piece of Boyle's time. The couple were spending less time together than they had hoped and their daughter Suzi was born.

But it was after the birth of their second child, son Kydd, that Sarah felt a rift between the two of them. Boyle arrived to pick them up from hospital in a Rolls-Royce. He said it had been donated to the Gateway Exchange by a rock star.

Trevelyan writes: "It was in these moments that the parting of the ways between Jimmy and I was beginning. The Rolls-Royce clashed completely with my image of what I felt we were about. We were working to help the underprivileged, the disadvantaged, the fringe dwellers of society. A Rolls-Royce belongs in another strata – a strata associated with wealth, largesse, consumption and excess.

"Although, and quite possibly because, I come from a privileged background, I carry a reverse kind of relationship with excessive displays of wealth. I don’t like them. I decided that for the most part I would regard the Rolls-Royce as his and that I wouldn’t ride in it."

Then to make matters worse in her eyes, Boyle started importing champagne. The casual clothes she so admired him in were now being replaced by smart suits while he dined with potential clients.

The Gateway Exchange ran out of funding and closed after five years. Meanwhile, a family friend who worked with them at the Gateway had turned to drugs, become paranoid and died of an overdose, but before doing so published his autobiography in which he claimed that he and Boyle had been lovers.

Well, that doesn't quite fit in with the Gorbals hard-man image. But Trevelyan tells me: "That was nonsense. I knew it was untrue."

Boyle, though, was spending more time in France. Perhaps it was easier to leave his past behind him where nobody knows your background. "There he was Monsieur Boyle and he would speak French with a Scottish accent," Trevelyan says, "but I'm not a wine and food person. I'd just get bored with the endless meals, talking about wine and food."

Then came what she described to me as "the biggest porkie pie you can imagine". She came across a letter addressed to her which she opened. Boyle had written it because of his fear of flying and it was only to be opened if he died. She didn't realise that, opened it, and discovered he had bought a villa on the Cap d'Antibe near Cannes without telling her. When she confronted him, he at first claimed that it had been left to him, and then he got angry at her for opening the letter – the classic diversionary tactic of someone caught out.

"What it represented was a breaking of trust, and that is very hard coming from someone you loved very deeply," she says. She described it in her book as a cleaver coming down that split their marriage.

Trevelyan visited the villa, which had a high wall and electronically-operated security gates. It was as if Boyle had substituted his old prison for a new one, albeit a luxurious one. "This is how the unconscious works. We actually recreate the very conditions we are trying to escape," she says. "We were going in different directions."

Back in Scotland, Trevelyan was training as a therapist, and examining her inner self through retreats such as Findhorn which she explains in detail in her book. But she had to accept that if they were living in different countries then the marriage was over. "Either we can understand that freedom is being outside the prison walls, but at a deeper level freedom is knowing who we are inside, and actually being able to live from that place in a way that's in balance, in harmony with oneself, with others, with nature."

Drinking wine over long lunches in France may seem like freedom, but are you really free? Trevelyan, who divorced Boyle, reverted to her maiden name, and for good measure dropped the "h" from Sarah as she never particularly liked it. Seems it's not just cockneys who drop their aitches.

She is well, she is happy, and has little contact now with Boyle, who has married a young actress and divides his time between France and Morocco.

Boyle has read the book and said he wonders why he never fought more for her. "He'd fought over so many things in his life but he didn't fight for me," she says.

Freedom Found by Sara Trevelyan is published by Scotland Street Press on March 6, priced £10.99. Visit scotlandstreetpress.com

Why are you making commenting on The Herald only available to subscribers?

It should have been a safe space for informed debate, somewhere for readers to discuss issues around the biggest stories of the day, but all too often the below the line comments on most websites have become bogged down by off-topic discussions and abuse.

heraldscotland.com is tackling this problem by allowing only subscribers to comment.

We are doing this to improve the experience for our loyal readers and we believe it will reduce the ability of trolls and troublemakers, who occasionally find their way onto our site, to abuse our journalists and readers. We also hope it will help the comments section fulfil its promise as a part of Scotland's conversation with itself.

We are lucky at The Herald. We are read by an informed, educated readership who can add their knowledge and insights to our stories.

That is invaluable.

We are making the subscriber-only change to support our valued readers, who tell us they don't want the site cluttered up with irrelevant comments, untruths and abuse.

In the past, the journalist’s job was to collect and distribute information to the audience. Technology means that readers can shape a discussion. We look forward to hearing from you on heraldscotland.com

Comments & Moderation

Readers’ comments: You are personally liable for the content of any comments you upload to this website, so please act responsibly. We do not pre-moderate or monitor readers’ comments appearing on our websites, but we do post-moderate in response to complaints we receive or otherwise when a potential problem comes to our attention. You can make a complaint by using the ‘report this post’ link . We may then apply our discretion under the user terms to amend or delete comments.

Post moderation is undertaken full-time 9am-6pm on weekdays, and on a part-time basis outwith those hours.

Read the rules hereLast Updated:

Report this comment Cancel