Just another day and another emergency evacuation in the most dangerous place in the world for an aid worker. It’s late Thursday evening and the team providing food and water in a remote camp in the South Sudan bush have been successfully extricated and returned to base in the capital Juba, all safe.

“The situation is unpredictable. There were armed groups roaming around so we had to evacuate,” Francesco Lanino, Acting Country Director of the aid group Mercy Corps calmly explains. He’s used to it. It happens, he says, that every day or two they have to pull out their teams operating in remote areas because of the threat from roaming gunmen, a by-product of the civil war which has been raging for four years.

Crises and emergency care are two things Lanino knows a lot about, he worked in Lebanon, Syria, Iraq for five years and now two in South Sedan with Mercy Corps “always in emergency situations…..I follow the crisis” is how he puts it.

It’s a country on fire, he says. “When I arrived here the incidents were relegated to just some areas. There were some very safe places. But everything has changed so fast, particularly since last July when the last peace deal broke down. It’s now totally different.”

At least 80 aid workers have been killed in the country in the last three years. Five foreign women were raped in a hotel in 2013, after the civil war broke out, and their colleague was shot dead. UN peacekeepers nearby were phoned for help but they refused to respond. Most of the attacks have gone unpunished.

South Sudan has been independent from its larger sibling, North Sudan, since 2011. It’s officially the youngest country in the world. It’s at the top, or near the top, of every humanitarian league table you’d want to be bottom of – the highest inflation on the planet at almost 900 per cent, the third-highest number of people who have sought refuge outside the country (after Syrian and Afghanistan, both bigger) with one-in-three of the population of 12 million having fled, political woes and war compounded by drought and cholera and over five million facing hunger with a similar number in need of aid.

The country ought to be rich, it has abundant oil reserves and the soil would be fertile, if it were farmed. But that’s all but stopped since the civil war which broke out almost four years to the day in 2013 when the president, Salva Kiir, from the majority Dinka tribe, accused his deputy, Riek Machar, of planning a coup.

But it would be mistake to conclude this is about ethnicity. It is about power. Ethnic groups from what were the two factions of government forces began fighting first in Juba, spreading to Bor and then to Bentiu, along the way bringing in most of the other smaller 62 ethnic groups, whose allegiance switches as they seek protection from one of the dominant warring groups or another.

This is a country awash with arms, with weaponry having been ploughed into the country by the United States, Egypt, Russia and China as geopolitical differences were fought out in real time and blood both before and after independence.

“It’s getting worse and worse and this is slowly moving forward to catastrophe,” Lanino predicts. “When I came here Bentiu was a thriving, bustling place with 150,000 people, with electricity, transport, a market, now it’s a ghost town of 10,000.”

However, he adds, if NGOs like Mercy Corps weren't on the ground “it would be much, much worse. We’re here to support the most vulnerable, to keep the tap open”.

Literally. Every day the organisation provides water to 80,000 people - “15 to 20 litres to every person every day”. As well as 20,000 cooked meals a day for schoolchildren.

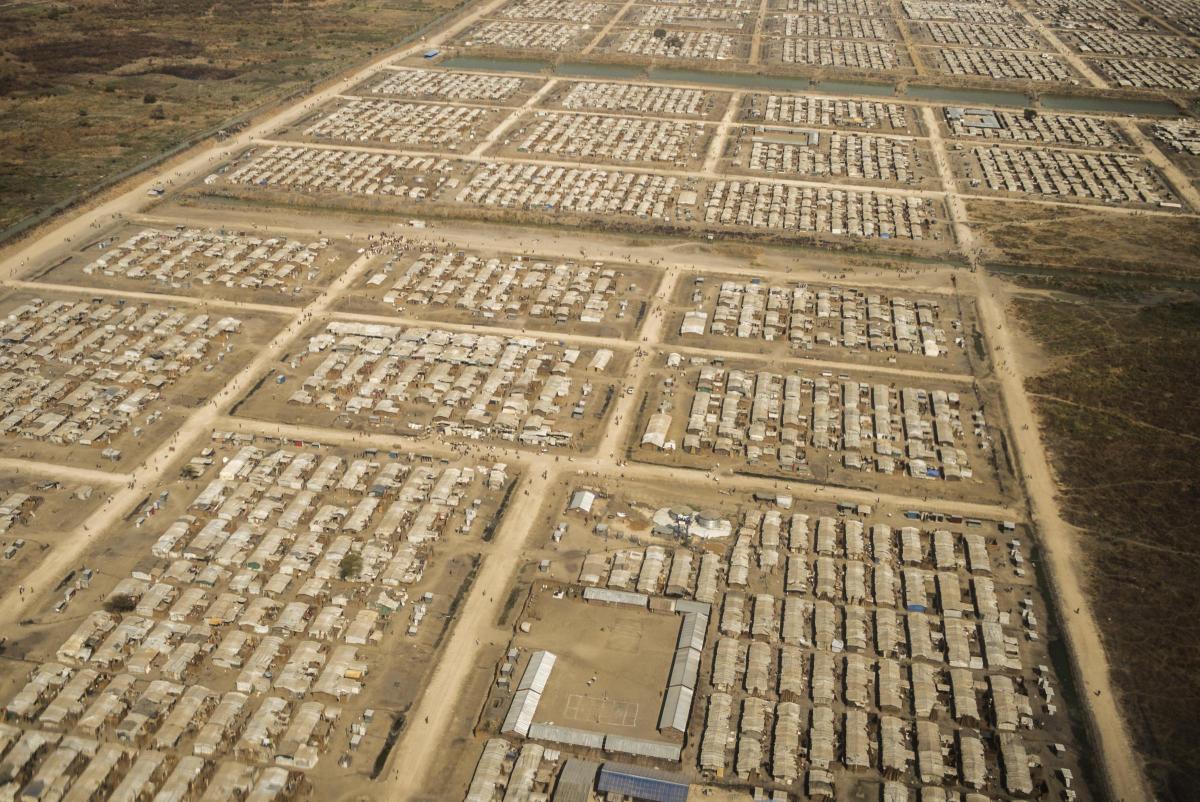

The UN has a peacekeeping force of around 4,000 in a country roughly six times the size of the UK, but it is almost exclusively deployed to guard the massive internal refugee camps where some of those who did not flee the country flocked to – a 150,000 encampment of shacks in Bentiu and another of 30-40,00 in Juba.

Mercy Corps set up subsidised schools in Bentiu and at first attendance didn’t get much above 50 per cent because, Lanino explains, kids were out in the bush scavenging for food, from flowers, berries, or trapping animals, whatever they could find or kill.

“So we set up a school feeding programme, with a cooked meal of beans and rice for 20,000 kids every day. They realised that they would get a meal every day and as a result attendance has gone up to almost 100 per cent.”

It costs just 1 cent a day to feed a child so, as Lanino points outs, “for $100 you can feed 1000 children a day”.

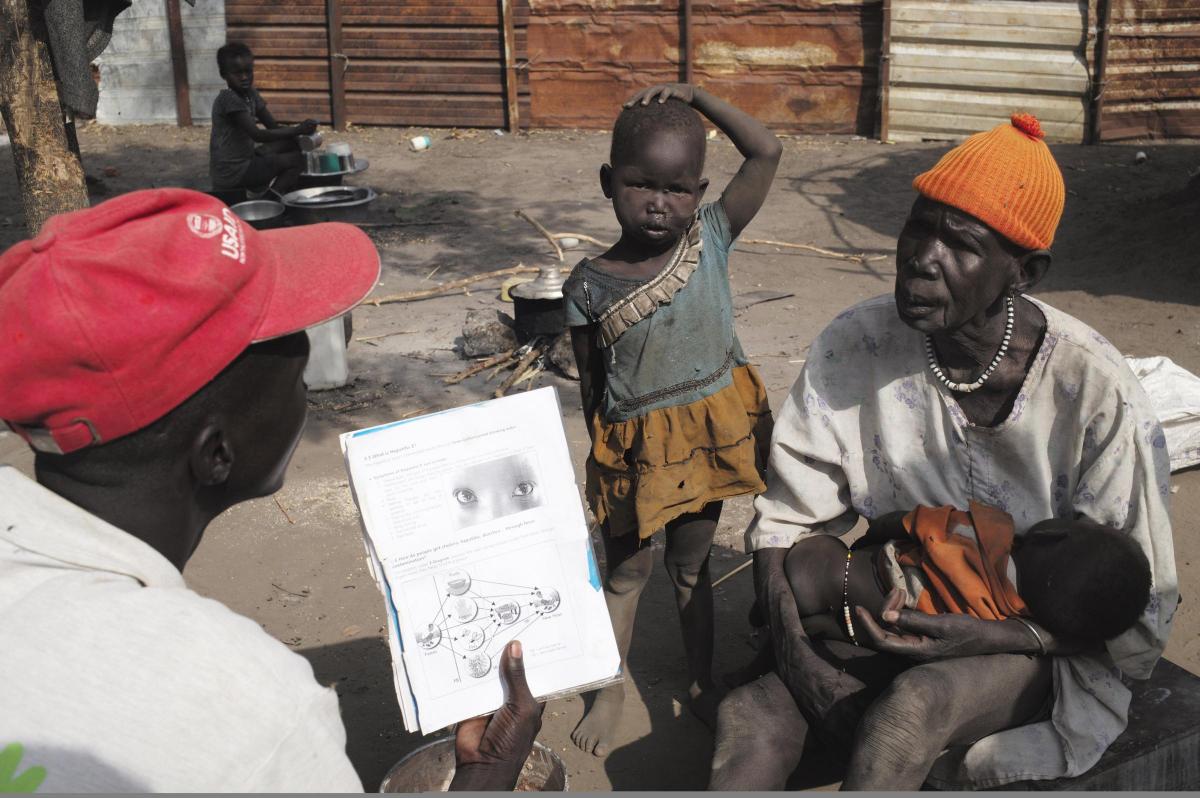

But it’s not just children. The charity, which has its European headquarters in Edinburgh, provides not just fresh water, but latrines for the camps, building one for every 30 people. “We still have a cholera outbreak in South Sudan and it can spread like wildfire if you don’t have strict hygiene,” he explains.

Another groundbreaking – or soil breaking – provision is to give seeds and agricultural tools to civilians. “One of the major problems is food insecurity, with few people able to farm because of the risk”

So, working with local communities and elders they set up secure areas – “although nowhere is 100 per cent safe” – where villagers can farm and produce crops.

The idea is to help rebuild the economy, too, by investing in local traders, so that if they are successful they plough the money into their local village economy. It’s the micro-finance model.

“The markets here are not functional,” says Lanino. “These people have no capital to invest so we provide selected traders with unconditional support. What they need is capital to start a business like they had in the past.” Mercy Corps gives grants or loans, typically $500, which could pay for seeds, tools or other equipment. The most vulnerable village families are also given grants, usually $20 a month, to pay all their food bills.

And do those they have invested in stick to the bargain and invest money back into their communities? “They are super faithful,” he responds.

“This country is in the toughest times in its history - which is saying something – and the international community, the UN, needs to find a way to find a solution in South Sudan. What is needed is a ceasefire so we can reach our beneficiaries safely. The international community needs to call now for an immediate ceasefire. And Christmas is the ideal time.”

SOUTH SUDAN: A HISTORY OF VIOLENCE

As in many other parts of the world Britain has a lot to answer for when it comes to South Sudan. In 1898 Lord Kitchener, he of the fulsome moustache and the jabbing finer urging young men into the trenches of the First World War, was sent to Sudan with an Anglo-Egyptian army to capture the country –but although this was claimed as a joint administration, the British Empire formulated the policies and supplied almost all the senior administrators.

The northern and southern parts of the country were treated as separate provinces, with the majority of the British focussed on developing the economy and infrastructure of the north, the Arab, Muslim part, a favouritism which continued for almost half a century until the country was prepared for independence, with a new government formed, which largely excluded southerners. Rightly they felt victimised.

The language of the new government was Arabic – and of the 800 new government positions which the British left in 1953, only four were given to the south.

Since independence in 1953 Sudan has been plagued by revolutions, coups d’etat and civil wars. In 1955, two years after the British departed, a mutiny by southern army officers sparked a 17-year civil was, in the early part of which hundreds of northern bureaucrats, teachers and civil servants were massacred.

In 1969, in another army coup, parliament and political parties were abolished. Throughout the 1970s, Egypt, the US and the USSR jostled with each other to supply weaponry, later joined by China. The country bristled with arms, tanks, missiles and other military hardware.

In 1987 the civil war in the south was reignited following the government’s Islamisation policy which would have instituted Sharia law. The fault line between the north of the country and the south is religion – and language – with the north overwhelming Muslim and Arabic-speaking with the south largely Christian. English is the official language in the south.

An elected government, which came to power in 1986, was again overthrown in a military coup led by Omar Hassan al-Bashir, who rules in the north with an iron fist to this day.

He has been a brutal overseer of Sudan, with arrest warrants against him issued by the International Criminal Court in the Hague, charged with genocide, war crimes and crimes against humanity. These relate to the conflict in western Darfur, where thousands of people died during fighting between the government and rebel forces.

In 2011 South Sudan gained independence following a referendum. Six years later the world's newest country is still engulfed in war and a massive humanitarian crises.

Two years after independence, in December 2013, the struggle for political power in the south erupted into violence with the president Salva Kiir, accusing his deputy Riek Machar of attempting a coup. Kiir is supported by the majority Dinka tribe while the Nuer tribe back Machar.

Tens of thousands of people have been killed in South Sudan since, in what the UN has called a campaign of ethnic cleansing. In 2016 a million people fled to neighbouring Uganda and since the start of the conflict one-in-three people have been displaced, some 3.7 milllion.

Predictably the economy is in crisis, with drastic food shortages verging on famine, the cost of food and services rocketing with an inflation rate of 835 per cent – the highest in the world – and almost five million, nearly half the population, in urgent need of humanitarian assistance.

South Sudan is also subject to arms and other sanctions from the UK, the US and the UN. But that has not stopped senior officials and armed group leaders close to President Kiir amassing millions of dollars offshore from what experts describe as a culture of corruption.

MERCY CORPS: THE FACTS

The organisation was formed in 1979 as Save the Refugees Fund 1979 by American Dan O'Neill who quickly partnered with Ellsworth Culver, involved with another charity, Food for the Hungry. The first project was in Honduras in 1982.

In 1996 Mercy Corps merged with Scottish European Aid and then set up its headquarters in Edinburgh.

The group has been involved in 107 countries across the world and today helps more than 19m people each year recover from disasters. More than 88 per cent of its income goes directly into aid.

Why are you making commenting on The Herald only available to subscribers?

It should have been a safe space for informed debate, somewhere for readers to discuss issues around the biggest stories of the day, but all too often the below the line comments on most websites have become bogged down by off-topic discussions and abuse.

heraldscotland.com is tackling this problem by allowing only subscribers to comment.

We are doing this to improve the experience for our loyal readers and we believe it will reduce the ability of trolls and troublemakers, who occasionally find their way onto our site, to abuse our journalists and readers. We also hope it will help the comments section fulfil its promise as a part of Scotland's conversation with itself.

We are lucky at The Herald. We are read by an informed, educated readership who can add their knowledge and insights to our stories.

That is invaluable.

We are making the subscriber-only change to support our valued readers, who tell us they don't want the site cluttered up with irrelevant comments, untruths and abuse.

In the past, the journalist’s job was to collect and distribute information to the audience. Technology means that readers can shape a discussion. We look forward to hearing from you on heraldscotland.com

Comments & Moderation

Readers’ comments: You are personally liable for the content of any comments you upload to this website, so please act responsibly. We do not pre-moderate or monitor readers’ comments appearing on our websites, but we do post-moderate in response to complaints we receive or otherwise when a potential problem comes to our attention. You can make a complaint by using the ‘report this post’ link . We may then apply our discretion under the user terms to amend or delete comments.

Post moderation is undertaken full-time 9am-6pm on weekdays, and on a part-time basis outwith those hours.

Read the rules hereLast Updated:

Report this comment Cancel