FOR a few brief shining moments, fifty years ago this week, Cumbernauld shared a global platform with the Beatles, Maria Callas and Pablo Picasso.

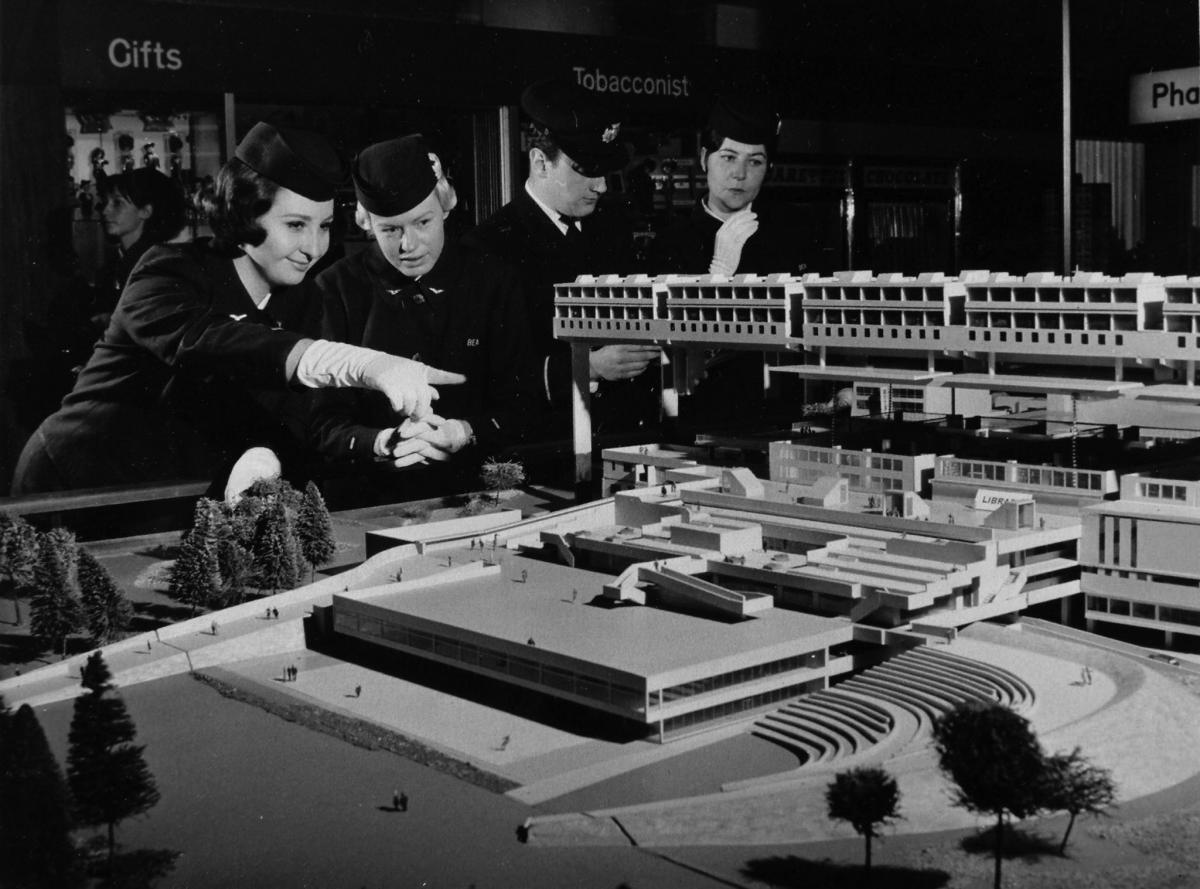

The Scottish new town, developed in the 1950s as part of the Glasgow Overspill, was featured in a pioneering broadcast screened on BBC1 which linked the world by satellite for the first time.

Entitled ‘Our World’, it consisted of live, non-political contributions from Europe, North America, Japan and Australia. The Russians, however, pulled out, reportedly because of then-current situation in the Middle East.

The BBC was the first broadcaster to attempt such a programme, and commissioned the Beatles to sing All You Need is Love. The audience was estimated in excess of 350 million.

The Cumbernauld segment, presented by Magnus Magnusson, was included in a passage about overcrowding, and the tyranny of the car. The “visionary” new town, he said, was at that time only one-third complete: when finished, it would be home to 70,000 people. Of the current 24,000 residents, over a third was under 15.

The first shops were already open in the elevated town centre, with not a car in sight. The town was looped by a road network and interchanges. The housing areas, each with a village shop, gave “mothers and children … the free run of cobbled paths, from which the car is banned”.

“This is the genius of Cumbernauld”, Mr Magnusson added. “Into a new town, planners have built all the calm of an old-world village”.

Among the programme’s vast audience on Sunday, June 25, 1967, was Kenneth Macdonald, now BBC Scotland’s Special Correspondent. “I saw it go out live”, he recalls. “It was the modern world then”.

“This was Scotland on a Sunday, so they had to open shops especially so people could pretend to buy things. And there were so few cars they too had to be pre-planned and ‘cued’ into shot by the director”.

By January 1969 however, architecture critic Ian Nairn was publicly wondering whether the “dream on the hill” had become a nightmare for residents, and mourning planners’ “inflexible and monumental thinking”.

In 2001 and 2005 Cumbernauld was the unwilling recipient of the ‘Plook on the Plinth’ title, though it did win, in 2012, the accolade of Best Town at the Scottish Design Awards.

Alan Taylor, the journalist and broadcaster who was part of the 2001 Carbuncle judging panel, said: “It wasn’t just Cumbernauld. There are a lot of places that have been blighted by civic planning. Everywhere became nowhere, and there was a spiritlessness and soullessness about town centres and public buildings and schools.

“These places were worse than most – usually linked to problems of local poverty but also to a lack of inspiration at the civic level and a desire to do things on the cheap.

“People were living in pretty grim inner-city conditions and were looking forward to living somewhere new and fresh, but unless places are properly managed, with places to ship and socialise, they are pretty terrible”.

Tom Johnston, who helps represents Cumbernauld East on North Lanarkshire Council, and has lived in the town since 1972, believes that Cumbernauld has been a success story.

“Its central location, midway between Glasgow and Edinburgh, and our excellent transport links are starting to pay off, and there’s a hugely improved route into Glasgow now. There has been a huge growth in private housing north of the A80. Of a population of around 60,000, there must be a good 30,000 north of the A80.

“Though there are still problems with the old town centre, the Antonine shopping centre certainly looks the part. Sanctuary Housing is making a real difference in new homes, and we’ve got a great film studio, Wardpark Studios, where they filmed the TV series Outlander”.

• Thanks to the BBC Scotland Archive for its assistance

* Carole Ewart, Convener of the Campaign for Freedom of Information in Scotland, remembers her childhood in Cumbernauld.

AS a child, my opinion was repeatedly sought by complete strangers, from all the continents, who wandered about Seafar, my local area, asking about what it was like to live in our iconic split-level house and in such a beautifully landscaped environment.

When I attended the Tufty Club (which focused on young children’s road safety) my opinion counted: when I complained that boys were driving the toy cars and only girls played pedestrians, action was taken to equalise things.

Imagine my excitement when a lady from the BBC turned up one day in 1967 with a clipboard. The BBC wanted my family to participate in a global TV programme, Our World, but my mother emphatically said ‘no’ despite my protestations. Many years later, I came to understand her concerns about privacy and family life. I’m still not over it, though, even after half a century.

Cumbernauld offered unconventionally designed homes. How exotic it was to have bedrooms downstairs, with living space above. Extensive pedestrianisation and low car-ownership meant that local people walked everywhere. That way, you got to know everyone.

People chose to move to Cumbernauld for different reasons. My parents, Ian and Agnes, agreed that it was an opportunity to sell their one-bedroomed Glasgow flat and move to a house in a green environment with their two daughters. Their ties with Glasgow remained strong, however, as we returned weekly to visit family and friends, to go shopping and visit the museums. In Cumbernauld, St Mungo’s Church was a major part of our lives as was voluntary work: we used our skills to make society fairer.

Homes were, overwhelmingly, rented, so Cumbernauld was a great social equaliser. Our friendly neighbours had an eclectic mix of jobs and interests. Their number included a draughtsman, a nurse, a Church of Scotland deaconess, a Post Office telephones worker, a bus conductress, an analytical chemist, a civil servant, and a Master of Works, to say nothing of various ladies who worked in shops and would wave at you when you passed by.

I have family and friends who still live in Cumbernauld. It is the place where I met my husband. And I believe it is a place that deserves greater recognition.

Why are you making commenting on The Herald only available to subscribers?

It should have been a safe space for informed debate, somewhere for readers to discuss issues around the biggest stories of the day, but all too often the below the line comments on most websites have become bogged down by off-topic discussions and abuse.

heraldscotland.com is tackling this problem by allowing only subscribers to comment.

We are doing this to improve the experience for our loyal readers and we believe it will reduce the ability of trolls and troublemakers, who occasionally find their way onto our site, to abuse our journalists and readers. We also hope it will help the comments section fulfil its promise as a part of Scotland's conversation with itself.

We are lucky at The Herald. We are read by an informed, educated readership who can add their knowledge and insights to our stories.

That is invaluable.

We are making the subscriber-only change to support our valued readers, who tell us they don't want the site cluttered up with irrelevant comments, untruths and abuse.

In the past, the journalist’s job was to collect and distribute information to the audience. Technology means that readers can shape a discussion. We look forward to hearing from you on heraldscotland.com

Comments & Moderation

Readers’ comments: You are personally liable for the content of any comments you upload to this website, so please act responsibly. We do not pre-moderate or monitor readers’ comments appearing on our websites, but we do post-moderate in response to complaints we receive or otherwise when a potential problem comes to our attention. You can make a complaint by using the ‘report this post’ link . We may then apply our discretion under the user terms to amend or delete comments.

Post moderation is undertaken full-time 9am-6pm on weekdays, and on a part-time basis outwith those hours.

Read the rules hereLast Updated:

Report this comment Cancel