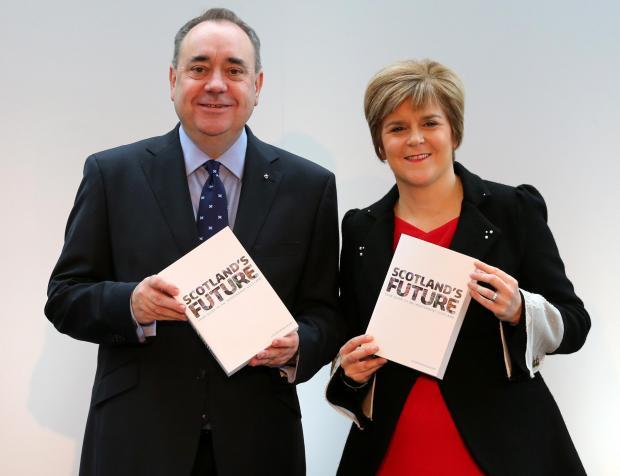

Tomorrow afternoon Nicola Sturgeon will be re-elected First Minister by new (and returning) Members of the Scottish Parliament, 30 years after she first joined the Scottish National Party as a teenager.

It was clear from pre-election interviews that Ms Sturgeon regarded securing her own “personal mandate” as very important, and while it’s not as “unequivocal” as she and her party would have liked, it remains the strongest in terms of votes (if not seats) of any First Minister since 1999.

Mandates, however, are more theoretical than real, particularly in a “balanced” Parliament. Here the rhetoric is interesting. Of the referendum result the First Minister often emphasises how “narrow” it was, while yesterday she wrote of having “fallen a whisker short of an outright majority”.

Read more: Nicola Sturgeon confirms intention to relaunch SNP's Independence campaign

There’s an implicit sense of “we wuz robbed” in this sort of stuff, while the irritation – mainly directed at the Greens – among SNP advisers is clear. Thus the election of Ken Mackintosh as Presiding Officer was contrived to remove another Unionist MSP, meaning the Scottish Government is within a single seat of having another overall majority.

But until God provides a by-election (tricky given the SNP hold most constituency seats) the SNP will have to make the best of the status quo. Rhetorically, to my ears anyway, the First Minister is still struggling to hit the right tone on this, fluctuating between talk of “consensus” and “compromise” to dire warnings to the opposition parties of, Lord forbid, playing politics.

Writing in yesterday’s Sunday Herald she said it was not for “the party which finished a distant second – or any of those which came after that - to dictate terms or to try and turn this session into one of obstruction for obstruction’s sake”. Voters, the First Minister added, wanted efficient government “unencumbered by political gamesmanship or needless politicking”.

All that’s fair enough, if a bit rich given the above critique could easily apply to the SNP group at Westminster, whose “obstruction for obstruction’s sake”, i.e. on fox hunting and Sunday trading, has punctuated the past year. In House of Commons terms the SNP finished a “distant” third, but while they have every right to “stand up for Scotland” it seems there’s a different rule for 31 Conservative MSPs at Holyrood.

Read more: I’ll persuade, not divide, says defiant Nicola Sturgeon

In a speech in Edinburgh today Scottish Secretary David Mundell will apply his own framing to the next Holyrood parliament, arguing that “people are sick and tired of the bickering and blame games” and want to see their politicians “working together for the common good”; he’ll offer to “reset the relationship between our two governments”. In other words, both the UK and Scottish Governments will depict themselves as consensual and blame the other if that breaks down.

Now Ms Sturgeon is correct to say that the opposition parties will have to compromise themselves, but the onus remains on the leader of the largest party. As the former Conservative Chancellor Nigel Lawson once remarked: “To govern is to choose”, while to appear “to be unable to choose is to appear to be unable to govern”.

And avoiding difficult decisions during this Parliament will be harder than ever before. As the academic Dr Jan Eichhorn of the Centre on Constitutional Change put it in an analysis of the election results late last week, the SNP “manages to be something different to different people”, indeed voters end up projecting on to the party what they themselves want it to be.

Until recently this had been easier to pull off due to almost annual electoral contests that allowed the SNP to appeal above the usual policy divisions to a catch-all sense of “Scottishness”. So in 2014 it fought the referendum on the basis of “social justice”, the 2015 general election on an “anti-austerity” platform and the recent election on an ostentatiously centrist agenda that marginalised the previous two rallying cries.

Read more: Sturgeon is poster girl for Tories and SNP

Between now and 2020, however, there will be fewer places to hide, and therefore Nicola Sturgeon will have to decide if she’s a rural or urban politician, tribal or consensual, centre-left or centre-right, pro-independence or a devolutionist (for the time being). In a recent article the political scientists Professor James Mitchell and Dr Rob Johns called this the SNP’s “central dilemma”, simultaneously building support for a radical constitutional agenda (independence) while also appearing “safe and competent”.

And as others have observed, the logic of the 2016 election result suggests the SNP will triangulate further to the right, not least because Middle Scotland clearly doesn’t want to pay even a bit more tax, and certainly not more than other parts of the UK. The First Minister will also have to muffle any talk of a second referendum, although a “Remain” vote in next month’s EU referendum should make that easier, for it would remove the most likely piece of “material change”. This summer’s independence “initiative”, meanwhile, will most likely be a low-key affair.

On the policy front there are also difficult choices. Reports suggest legislation governing offensive behaviour at football matches will be repealed, as could the similarly illiberal named-persons measure. And then there’s fracking. This, should Ms Sturgeon conquer her apparent “scepticism”, could easily pass on the basis of Tory votes, but at the same time infuriate the Greens and the SNP’s own left flank. The optics of that would be highly problematic, but it can’t really be fudged much longer.

In the past week the First Minister has emphasised education and the economy, perhaps seeing them as two areas where achieving a consensus will be much easier. On the former I suspect the Scottish Government will end up pursuing (a version of) self-governing schools, greater autonomy and standardised testing while selling them as “radical” and “progressive”, even though both those terms long ago lapsed into the platitudinous.

This will find what the authors of an engaging new polemic, Roch Winds: A Treacherous Guide to the State of Scotland, call the “Scottish ideology” increasingly creaking under the weight of its own contradictions, simultaneously committed to social justice and competition, universalism and “fairness” when it comes to the distribution of wealth. The SNP (and Scottish Labour before it) call it “social democracy”, when in fact it’s a bit of everything, an incoherent utilitarian nationalism that claims to benefit everyone equally.

While Alex Salmond always papered over these contradictions with slippery aplomb, switching between ideological guises depending on his audience, to my eyes his successor looks visibly uncomfortable when compelled to be similarly pragmatic, not least when it comes to taxation. And while she might have convinced herself that the views she holds now are consistent with those she held on joining the SNP in 1986, that doesn’t stand up to much scrutiny. The next few years, therefore, will test Nicola Sturgeon and her party more than ever before.

Why are you making commenting on The Herald only available to subscribers?

It should have been a safe space for informed debate, somewhere for readers to discuss issues around the biggest stories of the day, but all too often the below the line comments on most websites have become bogged down by off-topic discussions and abuse.

heraldscotland.com is tackling this problem by allowing only subscribers to comment.

We are doing this to improve the experience for our loyal readers and we believe it will reduce the ability of trolls and troublemakers, who occasionally find their way onto our site, to abuse our journalists and readers. We also hope it will help the comments section fulfil its promise as a part of Scotland's conversation with itself.

We are lucky at The Herald. We are read by an informed, educated readership who can add their knowledge and insights to our stories.

That is invaluable.

We are making the subscriber-only change to support our valued readers, who tell us they don't want the site cluttered up with irrelevant comments, untruths and abuse.

In the past, the journalist’s job was to collect and distribute information to the audience. Technology means that readers can shape a discussion. We look forward to hearing from you on heraldscotland.com

Comments & Moderation

Readers’ comments: You are personally liable for the content of any comments you upload to this website, so please act responsibly. We do not pre-moderate or monitor readers’ comments appearing on our websites, but we do post-moderate in response to complaints we receive or otherwise when a potential problem comes to our attention. You can make a complaint by using the ‘report this post’ link . We may then apply our discretion under the user terms to amend or delete comments.

Post moderation is undertaken full-time 9am-6pm on weekdays, and on a part-time basis outwith those hours.

Read the rules hereLast Updated:

Report this comment Cancel