THE year 1967 was a golden one in the history of popular music. It was the Summer of Love. It was the year of LSD, of the Monterey Pop Festival in California, of debut albums by such landmark American acts as Jimi Hendrix and The Grateful Dead.

It was an important year in this country, too. The Beatles released Sgt Pepper’s Lonely Hearts Club Band, which topped the album charts on both sides of the Atlantic and became a key part of the soundtrack to the Summer of Love. Rolling Stone magazine, in 2012, would describe it as the most important rock and roll album ever made.

But something else was stirring in this country: the rise of free festivals, and the countercultural spirit of protest that flourished within their confines. The year 1967 turned out to be a key moment for them, too.

"Free festivals" were events that made no charge at the gate. “They developed over time and became free, or some split, and became paid-for festivals,” explains Sam Knee, author of a new book on the phenomenon. “Really, festivals became two different entities over time: the paid-for ones became more of a corporate event, and they eventually superseded everything else.”

In Memory Of A Free Festival, he writes that the first wave of music festivals in Britain began in 1956, on the grounds of Lord Montagu’s stately home in Beaulieu, in Hampshire. It ran for five years and was attended, says Knee, “by droves of young bohemians putting their own spin on the US beatnik look”. Many of these “scenesters” were paid-up members of the Campaign for Nuclear Disarmament. “Peace-symbol CND badges became virtually obligatory," writes knee, "and were perceived as much anti-authority as anti-nuclear.”

But amid complaints about the Beaulieu festival’s alleged class bias, the 1960 event was marred by minor skirmishes between fans and security, and the 1961 festival proved to be the last. Other free festivals rose to fill the gap, but it was in 1967 that, says Knee, “all the strands of counterculture that had been bubbling beneath the surface erupted into sight. One year saw the establishment of the underground press, three key festivals and a ‘legalise pot’ rally in [London’s] Hyde Park”, attended by 5,000 hippies.

The festivals included the first Woburn Festival, and the 14-hour-long Technicolour Dream at London’s Alexandra Palace, featuring such prominent bands as Pink Floyd. The annual Hyde Park free festivals ran from 1968 until 1971. By 1969, says Knee, Britain’s festival scene had assumed monolithic proportions. The last great free festival of the decade was the Rolling Stones’ Hyde Park gig in front of an estimated 400,000 fans on July 5, 1969. It marked not only their return to live performance but also the debut of Mick Taylor, their replacement guitarist for Brian Jones, who had died just two days earlier.

Half a century years on from the Summer of Love, from that “legalise pot” rally, Britain’s music-festival scene has become a colossus. Dozens are staged each year, covering every musical genre. The annual Wish You Were Here report by UK Music, the campaigning and lobbying group, estimates that in 2015, festivals attracted 3.7 million fans and accounted for £921 million of direct spending by music tourists in the UK – a sum that includes such direct costs as tickets, travel, accommodation and money spent on-site. The figure for Scotland alone was £72 million.

Last weekend witnessed two major, long-established festivals: Download, the metal festival, at Donington Park, Leicestershire, and the Isle of Wight Festival – an event that was first held between 1968 and 1970. The latter’s headliners were David Guetta, Arcade Fire and Rod Stewart.

Glastonbury, which began in 1970 on the day of Jimi Hendrix’s death, and became Glastonbury Fair the following year, has become the biggest of them all. This year it will be held on June 21-25, with Radiohead, Foo Fighters and Ed Sheeran as the Pyramid Stage headliners.

In Scotland, T in the Park is taking a year-long break but in its place is TRNSMT, at Glasgow Green (July 7-9), with the bill being topped by Radiohead, Kasabian and Biffy Clyro. Oban Live, which took place on June 2-3, drew more than 8,000 fans, some of whom came from as far afield as Russia and the USA. Oban Live managing director Daniel Gillespie says: "We will take time to review the event with all the teams then look forward to making an announcement soon on Oban Live 2018."

Other high-profile festivals over the next few months include Latitude, in Suffolk (July 13-16; main acts are The 1975; Mumford and Sons and Fleet Foxes); Reading/Leeds (August 25-27; Kasabian, Eminem and Muse) and Bestival (September 7-10), the award-winning four-day boutique festival in Dorset.

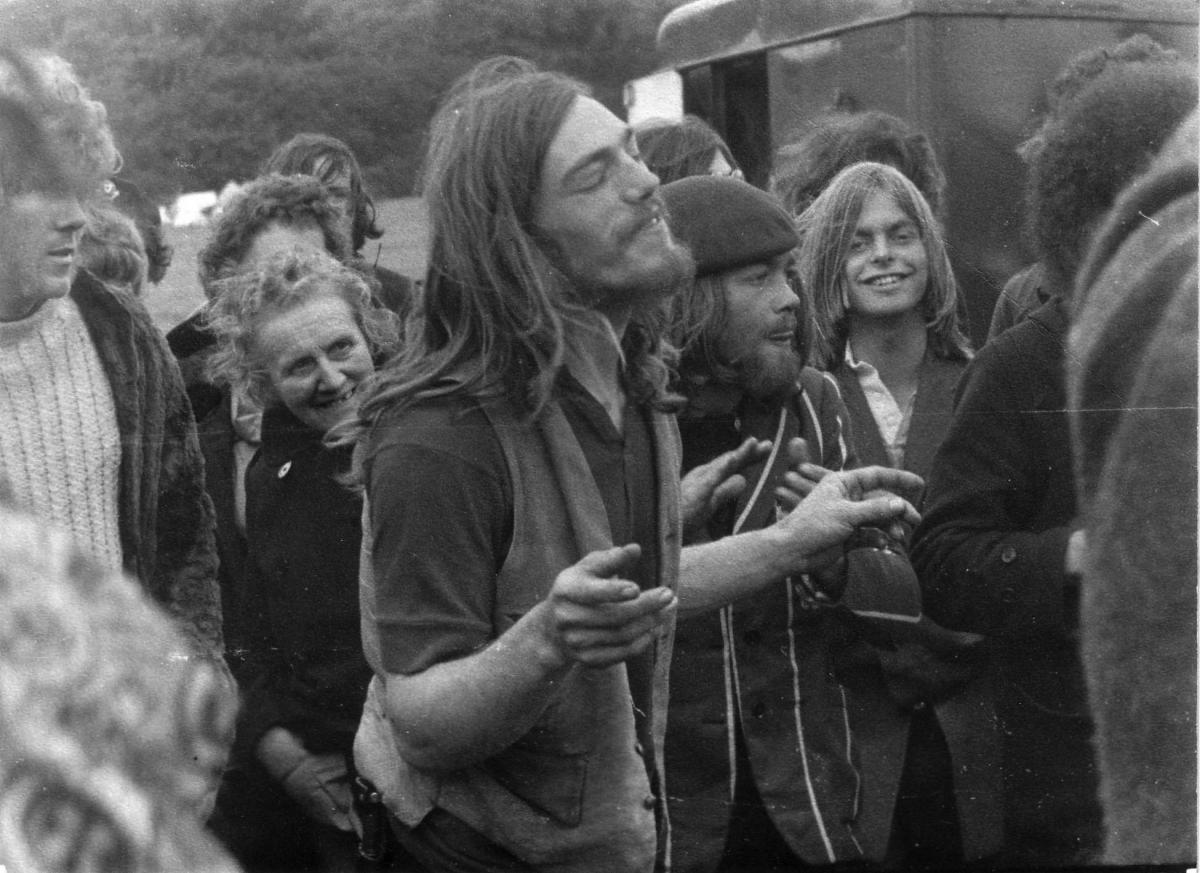

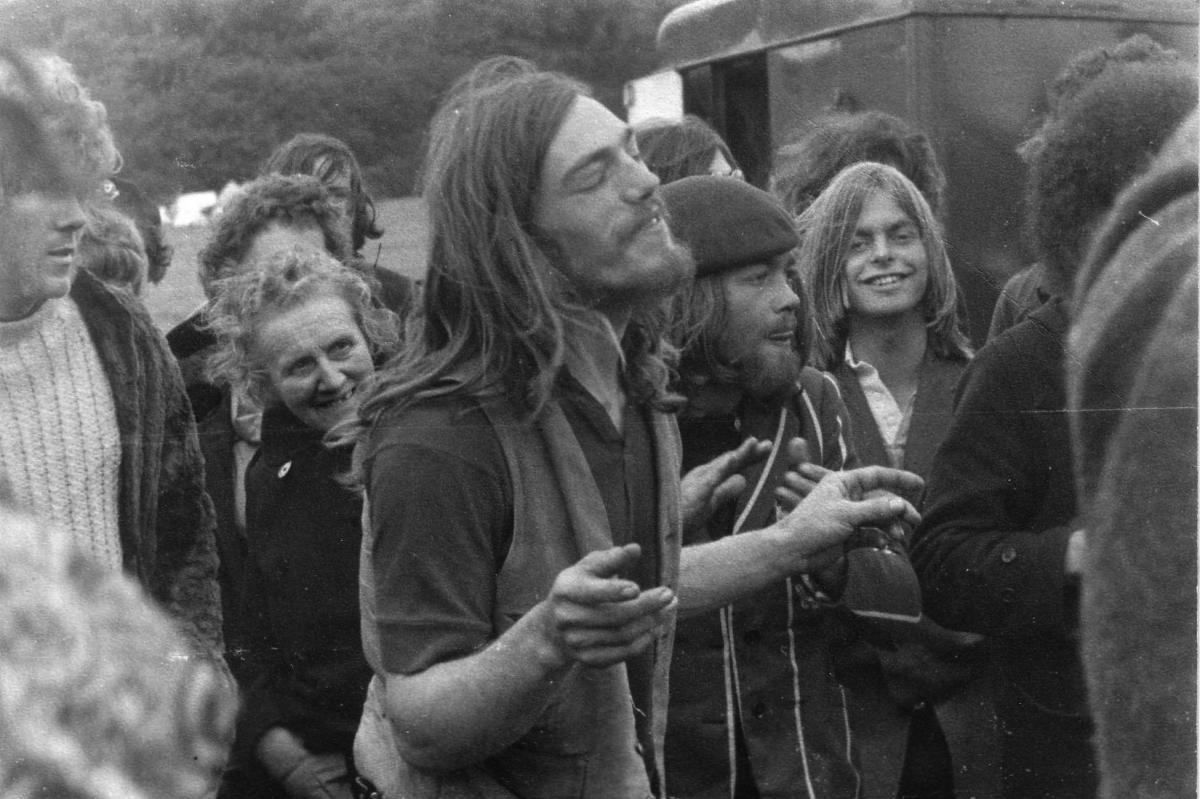

In this context it’s interesting to read Memory Of A Free Festival and study the history of these big outdoor events – and, in many cases, their counterculture aspects. The book is profusely illustrated with photographs and handbills.

Memory Of A Free Festival follows Knee's previous book, The Bag I’m In, which looked at underground music and fashion in Britain from 1960 to 1990. "I thought it would be interesting to ... compile a book on the peace movement and its evolution into the hippie movement and the growth of the free festival scene in particular," he says.

The early free festivals frequently revolved around what Knee terms “deeper issues around unemployment, racial prejudice and the nuclear threat”. His own parents, as it happens, were themselves firmly anti-nuclear, being committed members of CND in the late 1950s and early 1960s.

“The festivals back in those early days were places where you could almost say there was a gathering of the tribes,” says Knee, who is 50. “People realised how strong the movements were becoming. Ideas were exchanged and re-encompassed people’s beliefs. They would then go back to their towns and their universities, and those ideals would then spread further. I think that beyond the frivolity, the free festivals had a much deeper meaning. They gave the counterculture a real core and I think that was translated back into regular society.”

Flower-power was a cultural phenomenon in 1967 but, the book reminds us, it would soon take on a bolder form of politicised expression. The spring and summer of 1968 witnessed great demonstrations and art-school revolts, the most notable of them being the anti-Vietnam protest in Grosvenor Square, in London, when thousands of students and demonstrators clashed with police outside the US Embassy. On March 17, more than 200 people were arrested and 86 people were treated for injuries; 50 were hospitalised, including two-dozen police officers. Trouble would flare outside the Embassy again on October 27, when some 25,000 took part in a march.

A later strand of political protest was stirred in the 1970s, when the National Front movement was on the rise. The book says their extremist views were given “unnecessary airtime” when in August 1976 Eric Clapton “drunkenly declared his support for the intolerant, zealous Conservative minister, Enoch Powell” – the controversial figure who had, in April 1968, spoken of “rivers of blood” during a speech on race and immigration.

Two music journalists, Red Saunders and Roger Huddle, appalled by Clapton’s sentiments, got to work on an idea they had already had for a grassroots organisation known as Rock Against Racism, to provide vocal opposition to the National Front and encourage tolerance in young people.

A one-day music festival in 1978, organised by RAR and the Anti-Nazi League, saw 100,000 people march from Trafalgar Square to Victoria Park, where The Clash, one of the foremost punk bands of the day, performed an incendiary set. The concert, says Knee, “was a public demonstration of unity in the face of prejudice and hate”.

Free festivals may in time have given way to the huge, sprawling and expensive festivals of today but their countercultural spirit lived on for a while in acid-house culture and in the various rave scenes that proliferated throughout the 1990s. The festivals of old, Knee believes, were occasionally naïve but generally well-meaning efforts to form bridges to overcome broader social issues. But although they were largely peaceable, the media frequently mocked them and portrayed them as sordid or filthy, which did nothing to improve their image.

In reality, Knee believes, the free festivals were microcosms of society: “overnight cities of tents and polythene shacks: a New Jerusalem taking up temporary residence on England’s green and pleasant land … They were sites of multicultural music worship, where fellow fans and youth tribes congregated and intermingled, living off the land, sharing possessions, food, drugs and ideals.”

Could free festivals possibly make a return? “[Festival] ticket prices now have become ludicrous,” reflects Knee. “I think it would be great if someone would come up with the notion of bringing the free festivals back, but I don’t know if young people think that would be possible. They’ve grown up in times when all the festivals are tied into a corporate-type thing. They almost expect to pay [to get in]. They don’t think there’s an alternative.

“But it would be nice if someone could find land – from a farmer or somebody, who could give them the land for free – and get bands to appear who wouldn’t expect to be paid. That would be your free festival”.

The author also believes that the counterculture that nourished so many of the free festivals could stimulate today’s young people. “I really think at the moment that we are going through a dark period. The legacy of the free festivals would be if people could actually bring the old counterculture to a modern-day realisation. I think there would be a lot of hope there for people.

“I think we’re almost living in a Victorian age just now; I don’t know if even the subcultures as such, actual movements, exist the way they used to. I don’t even know if the counterculture exists any more, but it is always there to be reclaimed.”

If there is one lesson that today’s young people take from the book it’s that they should appreciate how previous generations coped and remained creative during times of political turmoil and state repression. The old free festivals – that brave, idealistic New Jerusalem – should, Knee asserts, inspire young people now to stand up and fight back through peaceful protest and create a brighter future.

• Memory Of A Free Festival: The Golden Era Of The British Underground Festival Scene is published by Cicada Books, £16.95

Why are you making commenting on The Herald only available to subscribers?

It should have been a safe space for informed debate, somewhere for readers to discuss issues around the biggest stories of the day, but all too often the below the line comments on most websites have become bogged down by off-topic discussions and abuse.

heraldscotland.com is tackling this problem by allowing only subscribers to comment.

We are doing this to improve the experience for our loyal readers and we believe it will reduce the ability of trolls and troublemakers, who occasionally find their way onto our site, to abuse our journalists and readers. We also hope it will help the comments section fulfil its promise as a part of Scotland's conversation with itself.

We are lucky at The Herald. We are read by an informed, educated readership who can add their knowledge and insights to our stories.

That is invaluable.

We are making the subscriber-only change to support our valued readers, who tell us they don't want the site cluttered up with irrelevant comments, untruths and abuse.

In the past, the journalist’s job was to collect and distribute information to the audience. Technology means that readers can shape a discussion. We look forward to hearing from you on heraldscotland.com

Comments & Moderation

Readers’ comments: You are personally liable for the content of any comments you upload to this website, so please act responsibly. We do not pre-moderate or monitor readers’ comments appearing on our websites, but we do post-moderate in response to complaints we receive or otherwise when a potential problem comes to our attention. You can make a complaint by using the ‘report this post’ link . We may then apply our discretion under the user terms to amend or delete comments.

Post moderation is undertaken full-time 9am-6pm on weekdays, and on a part-time basis outwith those hours.

Read the rules hereLast Updated:

Report this comment Cancel