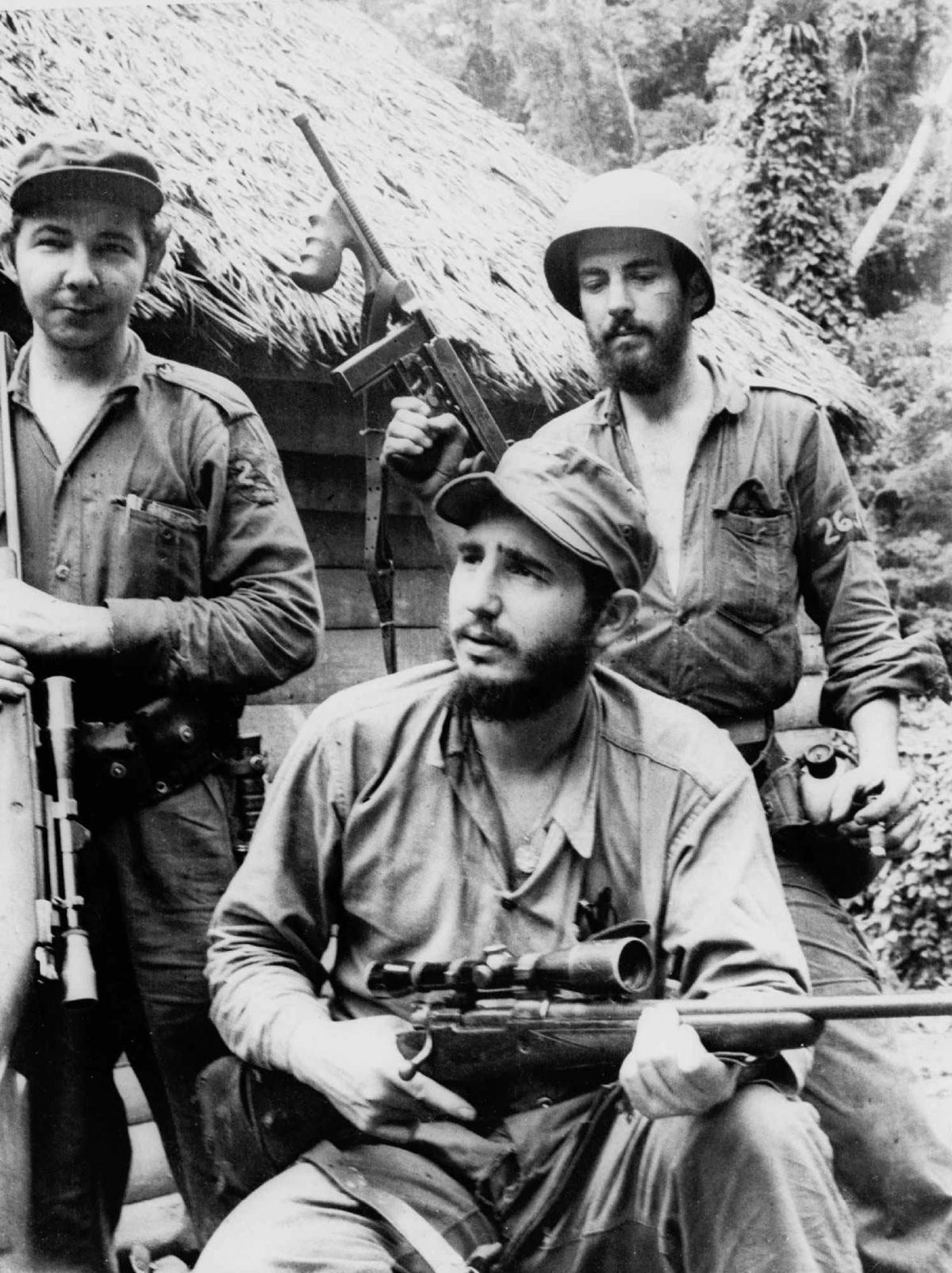

Former president of Cuba and leader of the Communist revolution

Born: August 13, 1926;

Died: November 25, 2016

BY MIKE GONZALEZ

FIDEL Castro, who has died aged 90, cast his ample shadow over the Americas for nearly 50 years. Few figures have excited such hostility or inspired such unconditional loyalty and neither will abate with his death, since the regime he created is unlikely to disappear with him. Its continuity was planned and organized well in advance by this most charismatic and most powerful of political leaders.

For the American right and the Miami Cubans, many of whom left the island soon after Castro's rise to power, he was a demonic presence, his existence a constant reminder of America's failure to control what it regarded as its own backyard. For most Latin Americans, by contrast, Castro’s Cuba was the rock on which the gunboats of the U.S. had foundered. The reward was Castro’s almost mythic status in the region and among many on the left elsewhere.

Yet that reputation rested largely on the achievements and political attitudes of the decade following the 1959 revolution. Thereafter, Cuba became a loyal member of the Soviet bloc, and its internal structures were barely distinct from those of the oppressive bureaucracies of Eastern Europe with which it was closely allied. Yet Castro largely escaped any comparison with the fallen leaders of pre-1989 communism; indeed his survival was celebrated by many as offering the one remaining beacon of socialism in the world.

Throughout the 1990s, Castro adeptly reshaped Cuba’s foreign policy and forged relationships with the capitalist market, accepting some of the conditions for survival in this new, “post-communist” world. Yet inside Cuba the instruments of control and repression continued to operate and all and any opposition met with fierce efficiency. The resolute refusal on the part of many socialists to recognise the social inequality and the lack of democracy in Cuba stemmed in part at least from the continuing intransigence of every US administration towards Castro. The unrelenting economic and political siege imposed by Washington, democrat and republican, ensured that he would continue to symbolize resistance to imperialism.

In fact, his pragmatism, an ability and willingness to adapt to circumstances with the sole criterion of saving the Cuban revolution, marked all the many years Castro was in power. It is ironic, for example, that the man who came to symbolize the continuity of Soviet-style communism after the fall of the Berlin Wall began his political career as a bitter antagonist of the Communist Party in Cuba.

Born into a wealthy landowning family of Spanish origin, Fidel Castro studied law at Havana University and stood as a candidate for the radical nationalist Ortodoxo party in the 1952 elections. The elections never took place; they were pre-empted by a military coup led by Fulgencio Batista, the corrupt and repressive figure who had dominated Cuban politics for most of the previous 20 years. Castro turned now towards a politics of armed opposition, in the belief that Batista and his US backers would never allow a democratic election to challenge their considerable interests on the island.

The first armed action, the assault by 165 men and women on the Moncada barracks on July 26, 1953, was a failure. Many were killed and Castro arrested and tried. His characteristically lengthy speech from the dock - “History will absolve me” - was a manifesto for an independent and free Cuba, but it was not socialist. Indeed Castro was deeply suspicious of socialist and communist ideas, because the Cuban communist party had collaborated with Batista in the 1940s.

Released two years later, Castro began to prepare for guerrilla war, and found a kindred spirit in the Argentine doctor, Ernesto Che Guevara, who joined his 26th July Movement when he was introduced to the charismatic Cuban in a friend’s flat in Mexico City. Together with 80 others, they sailed for Cuba in late November 1956. They were met by Batista’s troops and only 18 survived the dictator’s bullets. Yet just over two years later, on January 8, 1959, Castro would drive triumphantly into Havana while Batista sought refuge with his fellow dictator Trujillo in the Dominican Republic.

It would be hard to overstate the impact of the Cuban revolution across Latin America. Just five years earlier the US government had overthrown the Arbenz government in Guatemala for daring to challenge American economic interests in the region. Yet this small army of bearded young men (and a very few women) had successfully removed Batista and now promised to break Cuba free from its dependence on its mighty northern neighbour. Sugar was the island’s source of foreign earnings, much of it owned by the US, which was also Cuba’s main market. For the revolution, the key question was how to escape from that straitjacket.

That same relationship made Washington confident that it could easily break the Cuban economy by imposing a crippling economic embargo. US intentions were expressed most dramatically in its support for the counter-revolutionary invasion of the island at the Bay of Pigs in April 1961. The attempt was defeated, but Castro believed that this left little alternative but to develop the relationship with the Soviet Union, which in any event was already subsidising the revolution and buying Cuban sugar. That was the deeper significance of the announcement of the revolution’s turn towards Marxist-Leninism in August 1961. Rather than a major ideological shift, it was a pragmatic decision by Castro. And he made it in the usual spirited way, despite his earlier hostility towards Cuba’s communists.

One year later, in October 1962, that relationship would be tested to breaking point. The discovery of Russian missile bases in Cuba led to the last great Cold war confrontation between the US and the Soviets, until the Russians agreed to withdraw them. From Castro’s point of view this was an intolerable betrayal of Cuba. It led him to turn back to Che Guevara’s vision of an alternative alliance based on a proliferation of anti-imperialist struggles, the creation as Guevara put it of “one, two, three many Vietnams”.

This was the period of third world solidarity, of support for guerrilla struggles, of identification with all those in rebellion across the world. It was to be the source of Castro’s enduring image as a rebellious and intransigent guerrilla. Yet by 1967 it was already clear to Castro that there was no alternative to integration with the Soviets, no alternative revolutionary way forward. The death of Guevara in Bolivia in October of that year served only to confirm what Castro already knew - that the guerrilla phase was over. Cuba would survive by accepting a new dependency on the Soviet Union. Inside Cuba there were signs of discontent and frustration with a revolution whose promises were unlikely now to be fulfilled. The Revolution had created a fine education system and guaranteed high quality health care to every Cuban. But it was still a sugar producer dependent for its consumer goods and its energy on the Soviet bloc, starved as it was of both by the continuing US embargo.

Despite its romantic image abroad, the Cuban revolution was coming to resemble its eastern European partners in other ways too. Castro himself remained as the uncontested leader of the Cuban revolution. By the end of the sixties he headed the government, the army and the communist party. And while many have claimed that his power derived from the uncritical support of the Cuban people, this was never put to the test. The mass organizations - the Cuban Women’s Federation, the Trade Union Confederation, the Committees for the Defence of the Revolution - served the interests of the Cuban state and were firmly controlled from above.

By the beginning of the 1970s, Castro had taken Cuba into both the economic and political alliances of the Soviet bloc. At the Non-Aligned Meeting in Algiers in 1970, Castro represented the Soviet line. Cuban troops were sent to Ethiopia to assist the Soviet-supported government of the Derg against the Somali and Eritrean resistance. In Angola, Cuban troops played an important role in fighting off the South African-backed insurrection in the late 1970s.

But Castro was now an advocate of politics very different from the radical revolutionary ideas most closely associated with Guevara. He visited Chilean president Salvador Allende in 1971 to celebrate his “peaceful road to socialism” via the ballot box; he supported the Sandinistas in Nicaragua but counselled caution and negotiation. In Cuba itself, the continuing US embargo was used to justify the enormous concentration of power in the hands of Castro and his circle. And the internal discontents were dealt with by repression and control. When they rose too close to the surface, as they periodically did, Castro encouraged those who wished to go to leave for the U.S. In 1980, some 125,000 people left Cuba from the port of Mariel. Castro described them, in one of his many famous long speeches in Revolution Square, as scum; they were, he said, people who lack the revolutionary gene. Some of them were criminals or ex-prisoners, though this latter group included those persecuted for their homosexuality; the majority, however, were ordinary people who did not benefit from the privileges that came with membership of the communist party or the organs of the state and imagined they might find a better life in Florida.

The era of glasnost and perestroika threw Cuba into a profound crisis. The Rectification process launched by Castro in 1986 acknowledged corruption and inequalities in Cuba for the first time. More importantly, it was a re-affirmation of central control in anticipation of the crisis that would hit Cuba when Soviet subsidies and support were suddenly removed. The “Special Period in Time of Peace” brought the island to the brink of disaster - malnutrition reappeared, consumption of electricity was radically reduced, food was brutally rationed. The solution to the crisis was tourism, with a heavy emphasis on sex. A new class of wealthy Cubans benefitting from the new trade emerged, and the social differences became more pronounced than ever.

Yet at no stage was this voiced as a political challenge. While the personnel within the inner circle did change from time to time, those around Castro retained power without recourse to election or public ratification. Any challenge to Castro was represented as an imperialist conspiracy and opposition could be exported to the Florida coast.

The private Castro remained the subject of endless rumours. His enormously long public speeches and his tendency to interview foreign guests in the middle of the night gave the impression of a man with no private life. Married and divorced before the revolution, his son Fidelito is a nuclear scientist. The children of his long relationship with Celia Sanchez, have only recently emerged into the public gaze.

And Fidel’s legacy? He maintained Cuba’s independence through five difficult decades and survived the collapse of eastern Europe by taking Cuba back into a relationship with the world market. But there was no glasnost, no political liberalization in Cuba to accompany the relaxation of the economic rules. While he has left the succession in the hands of his brother Raul, the dedicated communist in the family, and the younger generation of party meritocrats like Carlos Lage, no-one will replicate his power and authority over the Cuban Revolution.

And for the 21st century Latin American revolutions, with their emphasis on grass roots democracy, Fidel Castro will leave them little in the way of lessons or models for the future.

Mike Gonzalez is Professor of Latin American Studies at the University of Glasgow

Why are you making commenting on The Herald only available to subscribers?

It should have been a safe space for informed debate, somewhere for readers to discuss issues around the biggest stories of the day, but all too often the below the line comments on most websites have become bogged down by off-topic discussions and abuse.

heraldscotland.com is tackling this problem by allowing only subscribers to comment.

We are doing this to improve the experience for our loyal readers and we believe it will reduce the ability of trolls and troublemakers, who occasionally find their way onto our site, to abuse our journalists and readers. We also hope it will help the comments section fulfil its promise as a part of Scotland's conversation with itself.

We are lucky at The Herald. We are read by an informed, educated readership who can add their knowledge and insights to our stories.

That is invaluable.

We are making the subscriber-only change to support our valued readers, who tell us they don't want the site cluttered up with irrelevant comments, untruths and abuse.

In the past, the journalist’s job was to collect and distribute information to the audience. Technology means that readers can shape a discussion. We look forward to hearing from you on heraldscotland.com

Comments & Moderation

Readers’ comments: You are personally liable for the content of any comments you upload to this website, so please act responsibly. We do not pre-moderate or monitor readers’ comments appearing on our websites, but we do post-moderate in response to complaints we receive or otherwise when a potential problem comes to our attention. You can make a complaint by using the ‘report this post’ link . We may then apply our discretion under the user terms to amend or delete comments.

Post moderation is undertaken full-time 9am-6pm on weekdays, and on a part-time basis outwith those hours.

Read the rules here