Whether by accident or design the themes which permeate the work that launched this year’s Edinburgh Film Festival could hardly be more prescient as Scottish golf clubs seek to address a century and a half of malpractice.

Wednesday evening’s premiere of ‘Tommy’s Honour’ was a grand affair at the capital’s Festival Theatre and its merits as a movie will be examined by those better qualified to do so.

It is, in essence, a love story and to those who have visited St Rule’s Cemetery, as my family did even before I knew there were golf courses in St Andrews, its basic elements are well known, while for those who do not know it any further description would represent something of a plot spoiler.

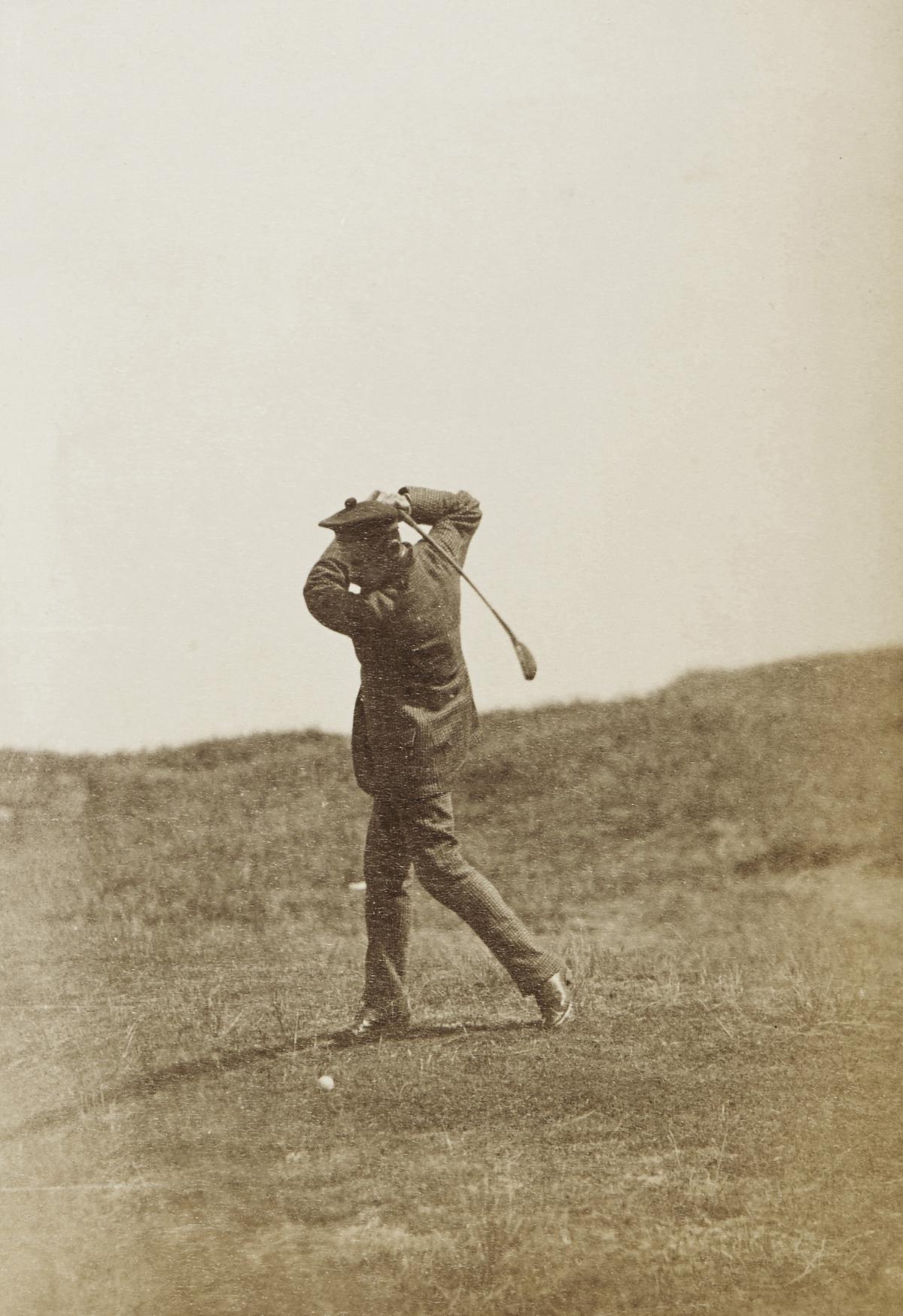

Just as there was when ‘The Herald’ gained exclusive access last year to St Andrew’s University’s discovery of the only known photograph of the younger of the Tom Morris’s who dominated the early competitive golf scene in the mid to late 19th century swinging a club on the links, there will be those who seek to question aspects of the film’s authenticity.

Just as historians at the University explained that it would have been necessary for Tommy to hold a pose that varied from his normal swing in order to accommodate the lengthy exposure required by photographers of the 1870s, so quibbling about the softening of North East Fife accents in order to engage the widest possible audience is far less relevant than the behaviour of the main characters and what that seeks to tell us.

Admittedly there has to be a suspicion that if Tommy’s mother was able to defend herself she might take exception to the representation of her severity as, if memory serves, Jennie Liddell, the sister of Eric did when that other great promotional tool for the Auld Grey Toon ‘Chariots of Fire’ became a worldwide success the best part of 40 years ago.

The unlikely nature of such a high percentage of the shots that had to be negotiated and which resulted in miracle recoveries that would have been beyond Seve Ballesteros or Phil Mickelson even with the best of modern equipment can meanwhile be excused as a filmic device, but while there is also a cartoonish element in the portrayal of the behaviour of those who carried influence in the sport and society at the time caricature is, of course, simply a case of accentuating existing characteristics.

What makes the way in which the snobbery and pomposity that Sam Neill exemplifies as captain of the R&A all the more telling is that the film is directed by a man who is the son of the R&A’s most famous member, but who has also achieved what he has from humble beginnings as a former milkman who was himself the son of a factory worker and a cleaner and, curiously, was widely known as ‘Tommy’, then ‘Big Tam’ in his younger days.

Jason Connery, son of Sean of course, depicts the R&A as an appalling group of grasping upper middle class chancers who mistake such irrelevances as accents and dress codes for marks of true gentility.

The sneering, cheating golfers of East Lothian also get harsh treatment which makes the decision to choose the word ‘honour’ in the film’s title seem very deliberate at a time when the attitudes that continue to afflict the area’s most famous club which plays on the Muirfield course that was, ironically, designed by Tommy’s father ‘Old Tom’ – played in the film by the wonderful Peter Mullan, mustering every ounce of gruffness and poignancy in his formidable armoury - are being examined in ways they should have been many years ago.

The contrast with, for all their inter-generational friction, the dignity and integrity the Morris’s are seen to represent is doubtless exaggerated and possibly unfair, just as it is wrong to think that the Honourable Company of Edinburgh Golfers’ bungling of their vote on whether to allow women to join their fraternity indicates that all members of male-only golf clubs are unreconstructed oafs.

What was clear from their vote was that the majority either do not fit into that category or at least understand the unacceptability of continuing to display publicly the worst of their prejudices, just as those running Royal Troon appear to have done a much more professional job of seeking to bring about the change required to make their club’s constitution less unappetising to wider society.

As a story in its own right ‘Tommy’s Honour’ was well worth the telling and the social history that it becomes a vehicle to examine is also interesting.

When Sam Neill’s R&A captain tells young Tommy that it matters not what his earnings from golf can buy him he will never attain the status of becoming ‘a gentleman’ the Dylanesque response is perhaps the film’s most important for the golfers in the audience.

“Times change,” says the cocky youngster. It is a message golf’s authorities and most influential clubs have taken too long to understand but perhaps, placed in the mouth of the man who is buried in that ornate grave in St Andrews and whose name is perhaps the most important in the sport’s history, it will now get through to even the most recalcitrant.

Why are you making commenting on The Herald only available to subscribers?

It should have been a safe space for informed debate, somewhere for readers to discuss issues around the biggest stories of the day, but all too often the below the line comments on most websites have become bogged down by off-topic discussions and abuse.

heraldscotland.com is tackling this problem by allowing only subscribers to comment.

We are doing this to improve the experience for our loyal readers and we believe it will reduce the ability of trolls and troublemakers, who occasionally find their way onto our site, to abuse our journalists and readers. We also hope it will help the comments section fulfil its promise as a part of Scotland's conversation with itself.

We are lucky at The Herald. We are read by an informed, educated readership who can add their knowledge and insights to our stories.

That is invaluable.

We are making the subscriber-only change to support our valued readers, who tell us they don't want the site cluttered up with irrelevant comments, untruths and abuse.

In the past, the journalist’s job was to collect and distribute information to the audience. Technology means that readers can shape a discussion. We look forward to hearing from you on heraldscotland.com

Comments & Moderation

Readers’ comments: You are personally liable for the content of any comments you upload to this website, so please act responsibly. We do not pre-moderate or monitor readers’ comments appearing on our websites, but we do post-moderate in response to complaints we receive or otherwise when a potential problem comes to our attention. You can make a complaint by using the ‘report this post’ link . We may then apply our discretion under the user terms to amend or delete comments.

Post moderation is undertaken full-time 9am-6pm on weekdays, and on a part-time basis outwith those hours.

Read the rules here