Little Sister

Dir: Zach Clark

(USA, 2016)

THREE STARS

Anchored by an exceptional performance from Addison Timlin as the little sister of the title (also a novice nun who has taken the name Joan of Arc), Zach Clark's study of a dysfunctional American family's cathartic reunion is defiantly indie in feel even if ultimately he soft pedals the issues he raises. After all, with a suicidal pot-smoking mother, a horrifically-injured Iraq veteran son and a religiously devout daughter all in play - and the whole thing unravelling against the background of the 2008 presidential election that put Barack Obama in the White House - you'd think the stage would be set for a dark, searing, state-of-the-nation address. But anyone looking here for a Ken Loach-style political and social broadside will be disappointed. Instead we get a kooky story about could-be-anywhere middle-class life.

After three years away from home, Colleen (Timlin) is persuaded by her mother Joani (Ally Sheedy) to leave her religious community in New York and return to see her big brother, Jacob. He lost most of his face in a bomb attack in Iraq and now sits in his room in sunglasses, hidden behind a drum kit that he plays incessantly or watching porn on his laptop. Colleen tries to reach out to him by transforming into her younger self, a Marilyn Manson-loving Goth. It works. She also reconnects with old high school friend Emily Molly Plunk), an animal rights activist who sits at home building pipe bombs (another storyline that promises weight but never really goes anywhere). Unsurprisingly, everything turns out more-or-less OK in the end - despite the hash cakes Joani makes for the family's climactic Hallowe'en party.

BARRY DIDCOCK

Zero Days

Dir: Alex Gibney

(USA, 2016)

FOUR STARS

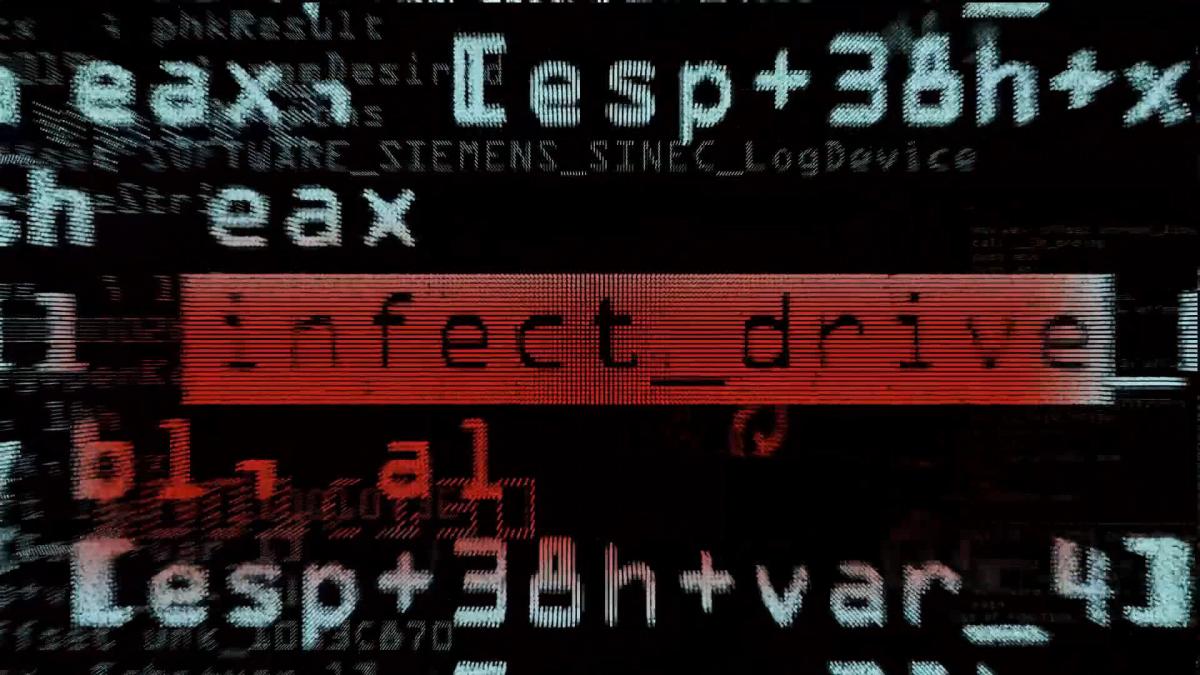

Documentary-maker Alex Gibney, winner of an Academy Award and several Emmys, has a long history of tackling big subjects. His Oscar came for a 2007 film about CIA torture tactics and among his other works are exposes of the Church of Scientology, scandal-hit energy company Enron and the Catholic church. Here he delves deep into the origins of the Stuxnet virus, which was first observed by a Belorussian cybersecurity expert in 2010.

Anyone who has followed the story or read any of the excellent long-form journalism which has dealt with it, will know that it's widely believed to have been cooked up by the Americans and the Israelis to target centrifuges in an Iranian nuclear facility. Gibney makes that case definitively. What he also does (and does excellently well) is show how they did it, why they did it and what happened as a result. To help him, he gathers an impressive array of cybersecurity experts, soldiers and high-level spooks who talk with varying degrees of candour about the project, known to the security services as Operation Olympic Games. Using an actor whose face is rendered digitally, Gibney also gives voice to several anonymous sources within the National Security Agency (NSA) whose testimony reveals how controversial the programme was internally.

This forensic analysis of Stuxnet's genesis and roll-out is gripping enough. But it's when the interviewees start to posit bigger questions about the use of cyber-warfare by nation states that Zero Days becomes really interesting. One talking head refers to cyber-warfare as the new, fourth arm of the military, and just as important in the 21st century as the air force was in the 20th. Another likens Stuxnet's use to the dropping of the nuclear bomb on Japan – an act of war with a catastrophic new weapon from which there is no going back. Someone else notes that it took 30 or 40 years to put in place legal and political controls on the use of nuclear, chemical and biological weapons but nobody is doing it for cyber-warfare. Nor is anyone likely to start soon: how can they, when nobody will even admit that they have the capability? Scary stuff.

BARRY DIDCOCK

Why are you making commenting on The Herald only available to subscribers?

It should have been a safe space for informed debate, somewhere for readers to discuss issues around the biggest stories of the day, but all too often the below the line comments on most websites have become bogged down by off-topic discussions and abuse.

heraldscotland.com is tackling this problem by allowing only subscribers to comment.

We are doing this to improve the experience for our loyal readers and we believe it will reduce the ability of trolls and troublemakers, who occasionally find their way onto our site, to abuse our journalists and readers. We also hope it will help the comments section fulfil its promise as a part of Scotland's conversation with itself.

We are lucky at The Herald. We are read by an informed, educated readership who can add their knowledge and insights to our stories.

That is invaluable.

We are making the subscriber-only change to support our valued readers, who tell us they don't want the site cluttered up with irrelevant comments, untruths and abuse.

In the past, the journalist’s job was to collect and distribute information to the audience. Technology means that readers can shape a discussion. We look forward to hearing from you on heraldscotland.com

Comments & Moderation

Readers’ comments: You are personally liable for the content of any comments you upload to this website, so please act responsibly. We do not pre-moderate or monitor readers’ comments appearing on our websites, but we do post-moderate in response to complaints we receive or otherwise when a potential problem comes to our attention. You can make a complaint by using the ‘report this post’ link . We may then apply our discretion under the user terms to amend or delete comments.

Post moderation is undertaken full-time 9am-6pm on weekdays, and on a part-time basis outwith those hours.

Read the rules here