Immortal Memory: Burns and the Scottish People

Christopher A Whatley

John Donald/Birlinn, £14.99

Review by Brian Morton

THE internationalisation of the Burns cult – he’s even more widely appreciated worldwide than a later poetic Bob – has tended to blur his importance to Scotland. The message of universal brotherhood has more heft and carry, but as Christopher Whatley shows in this finely argued and richly illustrated study Burns exerted a defining influence on the rise of a new conception of Scottishness.

Its beginnings lay in the early Victorian era and the time of the first Reform Act, continued through the 20th century wars, and is still powerfully with us, though perhaps still not quite free of its larval casing.

In the course of his argument, Whatley makes reference and comparison to a number of other literary cults. Shakespeare’s is the most obvious. That of Sir Walter Scott offers a genteel alternative to Burns’s but Whatley also mentions Goethe, Handel and the 19th century Catalan poet Jacint Verdaguer, and suggests that for democratic intensity, range of articulations and social penetration only the posthumous cult of Friedrich Schiller (died 1805) comes close to our Scottish model. In Great Deaths: Grieving, Religion, and Nationhood in Victorian and Edwardian Britain John Wolfe argues that the death – especially if early – of a creative figure prompts the “assertion of a transcending reality” which leads a people away from the muddy graveside and toward “the intensified expression of the shared values and convictions of the group as a whole”. Whatley’s examples are arguably more elevated, but isn’t that somewhat similar to what we experienced with the deaths this year of Leonard Cohen and, earlier and more obviously, David Bowie? The most visible of the constituencies which claimed Bowie’s spirit as its own was the cohort who grew up and did its experimenting with dress, drugs, gender and identity between 1970 and 1990 and which now effectively runs the news and cultural media. But, as with Burns two centuries before, everyone had a timeshare on Bowie’s legacy. The Catholic press found the language of salvation and redemption in the lyrics. The fine arts people determined that he wasn’t really a singer at all, but a performance artist whose collections were more significant than his albums. Likewise with Cohen who also usefully presents as Jew, Catholic, Zen Buddhist, as poet and novelist, bedsit bard, rampant lover, errant, philosopher, clown, singer/non-singer, so many identities and locations that he belongs to whoever claims him.

Chapter by chapter, Whatley shows how Burns was successively appropriated by different interest groups and political strata within Scotland. We’ve always been alert to the ambiguities in Burns: a philanderer who wrote the greatest and highest-minded love lyrics of all time; a libertarian who worked for the excise and who might well have ended up running slaves in the West Indies; a Scotsman and a kind of would-be Englishman; a freemason and a hater of the esoteric; a farmer (and perhaps not as bad a farmer as some accounts have it) and a foppish intellectual. Perhaps surprisingly, Burns was first co-opted by the improving Tories of early 19th century Scotland, later by Chartists and Radicals, then by Home Rulers and by a fully-fledged independence movement, but also by socialists and collectivists of every sort; just about everyone, in fact, except the Church of Scotland, who were obliged to regard Burns as a bit of a moral menace and his cult a potential rival to their own. By the end of the Napoleonic Wars, the smallest cotter’s shelf held a Bible and Burns. Even where literacy had not penetrated, his songs were known and sung.

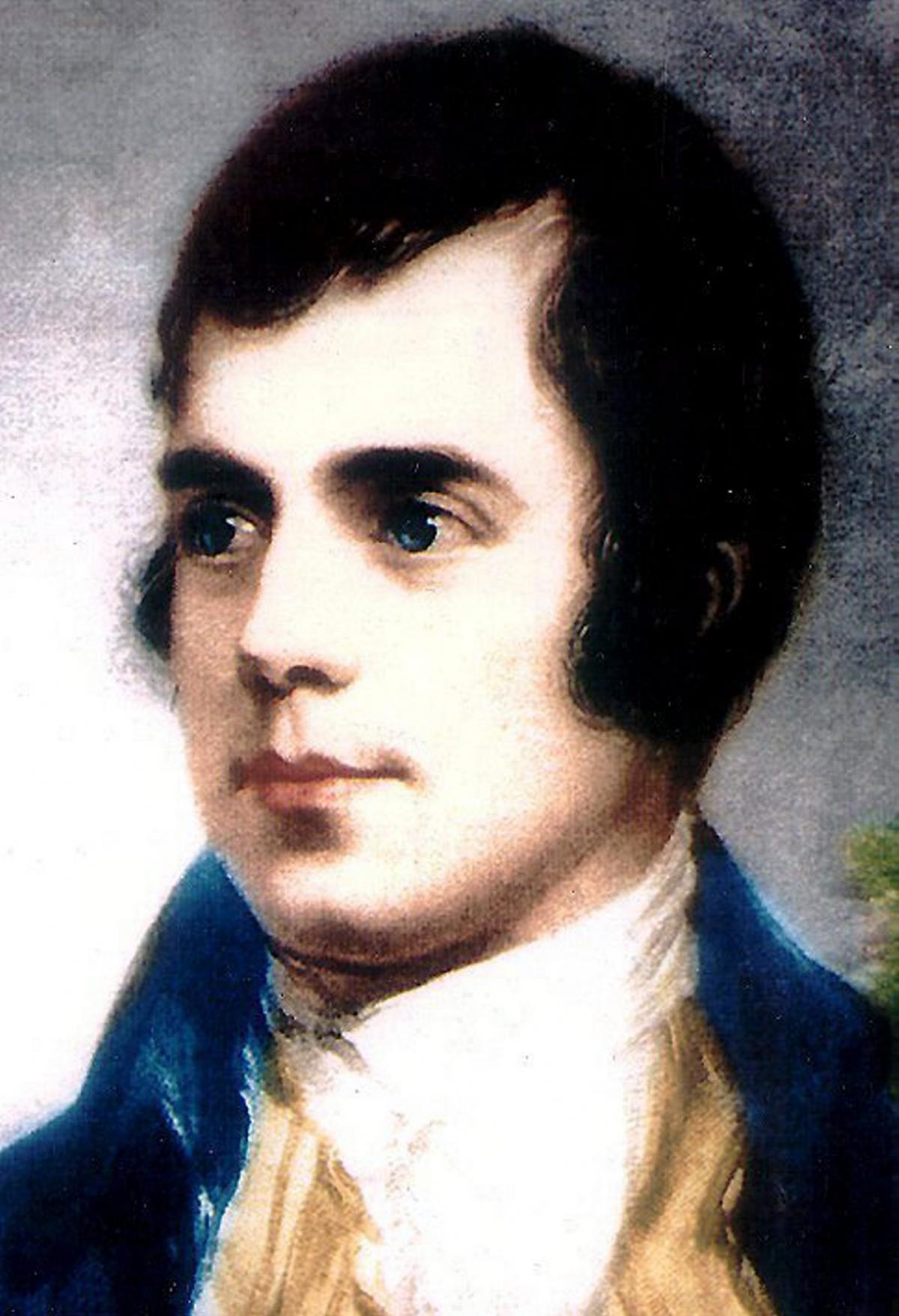

The iconic aspects of the cult are summed up in the myriad versionings of the Nasmyth portrait that started to turn up on decorative medals, Mauchline ware, large-edition etchings, whisky labels and haggis wrappings. A Burns supper – originally a dinner and safer so described – sounded uncomfortably like another meal conducted among men in an upper room and associated with both death and immortality. For the Kirk, a Burns supper was a blasphemous reworking of the Last Supper. Given that witches and devils were regularly invoked as such, as well as universal equality, there was easy leverage for clerical protest. Burns showed his own colours in the Prayer of Holy Willie, a Canting, Hypocritical, Kirk Elder, a poem never intended for more than private consumption but printed as an unauthorised and anonymous chapbook in 1789, the year of revolution, by which time it and other poems were already widely known.

Burns joins Jesus, His Mother, Lenin, Mao and Christopher Columbus as one of the most widely represented historical figures in human history. One of the most fascinating aspects of Whatley’s account, and the main thrust of his excellent selection of black and white photographs, is how Burns was represented in civic statuary, not just in his native Ayrshire but in all of Scotland’s major towns and cities, often with a public fountain nearby. George Ewing’s representation for George Square in Glasgow was liked by Glaswegians but condemned by others as sonsie and soulless (and dwarfed by a neighbouring memorial to Scott). Sir John Steell’s semi-draped figure for Dundee manages to combine both classical and Baroque elements and turns Burns from a brooding agriculturist into a mystic (heav’n-taught ploughman into heavenward-gazing visionary). Amelia Hill’s marble figure for Dumfries may have been hewn by Carrera anarchists, but gives Burns an ummistakably religious aura.

The co-presence of Burns and Bible in the humblest homes was an indication of perhaps the most important posthumous role the poet and his work were to play in one of the most massively uneven social structures in Europe. On this last point, almost all observers were to agree. The idealised family group of The Cottar’s Saturday Night was an image of the model domesticity landowners hoped to find among their tenancy but in which they were mostly disappointed. From the tenants’ point of view the same poem represented a certain aspirational vision of how they might live. When Whatley says “Dignity, self-respect and a sense of self-worth were of fundamental importance for working people in the nineteenth century”, what sounds like a truism or a statement of the blindingly bloody obvious is actually a quite specific and fundamental historical process of change, an emergence from the peasant mire of the previous century. In 1856, just a couple of years before the first centenary celebrations that are an obvious and key focus of Whatley’s survey and in the last months of his own perfervid life, Hugh Miller wrote that “Robert Burns was the man who first taught the Scottish people to stand erect”, using italics to make sure the point was rammed home. That’s no small claim – particularly given Miller’s concerns about Burns’s immorality – and one usually reserved for national liberators, guerrilla leaders and revolutionaries, not for poets. The analogy with Bowie still just about stands up. Both were figures who through memorable imaginative expression helped to set free a generation, the memorability being doubly important in a still substantially unlettered society and no less so in a society flooded with messages.

The vectors of Burns’s influence can seem tawdry and blanded to the point of insignificance. There are few calendar occasions more dispiriting than a riotous Burns supper from which the spirit of the dedicatee – or just one of the many spirits that seem to have inhabited him – is conspicuously absent. And yet, as Whatley shows here, Burns plays a central role in the development of Scottish identity and purpose and in its remarkably diverse means of expression. Those are a direct reflection of his complex nature. Previous historians – Sir Tom Devine, Christopher Harvie, T. C. Smout, Michael Fry – have tried to locate Burns in the history of his time. None, surprisingly, have until now gone the extra yard and shown how much of our time was shaped by his presence and even more by his early absence.

Why are you making commenting on The Herald only available to subscribers?

It should have been a safe space for informed debate, somewhere for readers to discuss issues around the biggest stories of the day, but all too often the below the line comments on most websites have become bogged down by off-topic discussions and abuse.

heraldscotland.com is tackling this problem by allowing only subscribers to comment.

We are doing this to improve the experience for our loyal readers and we believe it will reduce the ability of trolls and troublemakers, who occasionally find their way onto our site, to abuse our journalists and readers. We also hope it will help the comments section fulfil its promise as a part of Scotland's conversation with itself.

We are lucky at The Herald. We are read by an informed, educated readership who can add their knowledge and insights to our stories.

That is invaluable.

We are making the subscriber-only change to support our valued readers, who tell us they don't want the site cluttered up with irrelevant comments, untruths and abuse.

In the past, the journalist’s job was to collect and distribute information to the audience. Technology means that readers can shape a discussion. We look forward to hearing from you on heraldscotland.com

Comments & Moderation

Readers’ comments: You are personally liable for the content of any comments you upload to this website, so please act responsibly. We do not pre-moderate or monitor readers’ comments appearing on our websites, but we do post-moderate in response to complaints we receive or otherwise when a potential problem comes to our attention. You can make a complaint by using the ‘report this post’ link . We may then apply our discretion under the user terms to amend or delete comments.

Post moderation is undertaken full-time 9am-6pm on weekdays, and on a part-time basis outwith those hours.

Read the rules here