By Bill Jones

In the summer of 1968 – like thousands of schoolchildren before and after me – I found myself staying in a rusty Nissen hut in Perthshire.

The occasion was an ‘arduous training’ camp organised for my school cadet group of which I was a reluctant, CND-supporting, member.

Two things stuck in my memory when our bus took us home from that week in the shadow of the Highlands.

The first was the music. Every night, we’d congregate after dark around a transistor radio, thrilling to the greatest soundtrack of any year. Ever.

The Beatles. Joe Cocker. Fleetwood Mac. The Doors. Otis Redding. And so many more.

The second was how we’d all hated the place – which was known to one and all as Cultybraggan Camp – and yet none of us knew why. Just something creepy which thirty or so 14-year-old boys had all felt, and were more than happy to leave behind amidst the sheep and the bracken.

Fast forward forty odd years, and I was looking for an idea for a third book. Writing full time is a career I’d come to quite late, and with two successful biographies under my belt (both about deeply unhappy high achieving men) it had to be something new, something radically different.

In a previous incarnation, as a documentary film-maker, I remembered a programme I’d made in 1989 about a German POW who’d married into a North Cumbrian farming family after the war; a man who had stayed in England and now spoke in a curious accent, half-Hamburg, half-Penrith.

It was a voice which had stayed with me. As had a fascination for the clash of cultures and ideas which lay behind the extraordinary flood of captured Germans into Britain during the months which followed D-Day. Tens of thousands of beaten soldiers had arrived here within weeks of the Normandy invasions. Many thousands more would follow before Hitler’s death in 1945.

Who were they? Where had they all gone? How long were they here? Who guarded them? In what conditions did they live?

They were questions which very quickly led me back to a place I’d almost forgotten.

Back to Cultybraggan Camp…..back to the Nissen huts….and way back in time for an explanation for those feelings of unease which had dogged my teenage stay there so long ago…..

As it happened, there was no secret about what had happened there. It’s just that nobody had told us, and – the more I understood about the story – the more I understood why.

Because what actually transpired is one of the most horrific non-combat stories of the war. And if I’d known all about it when I was fourteen, I wouldn’t have slept for a week. Or maybe a year.

Back in the war it wasn’t known as Cultybraggan, it was Camp 21; the final dumping ground for the recidivists of Hitler’s army; the SS fanatics and diehards incapable of accepting that their war was over or that the tide of Nazism had been turned.

And in December, 1944 – under the curved corrugated iron of Hut No.4 – five of them had battered one of their own compatriots to death before stringing his corpse up in a latrine.

Within less than a year, the five had been identified, tried and hanged in Pentonville Prison. The oldest of them was 21. The youngest around 18.

Every research route I took led me back to this story, and within a few weeks – for only the second time in my life – I was back up there to investigate. Snow laced the horizon, and smoke rose steadily from Comrie’s chimney pots.

Absolutely nothing had changed. Now a listed building, the camp stood mostly empty under bitter February skies, and it was colder in the huts than it was outside them.

Standing there, watching snow settle on the backs of sheep, I knew that I had to somehow tackle this story. But how?

All my life I’ve dealt in facts - either in print or on television – and yet so few facts cling to either the perpetrators or their victim. How could I write a non-fiction book with so little to go on?

Postponing my decision, I headed for one of the most moving – and unknown – spots in England; the hideaway cemetery in the Midlands for German service personnel who died on British soil during World War Two.

Here rest pilots shot down in the Battle of Britain; submariners plucked from flaming oil slicks in the English Channel; and prisoners who succumbed to illness, or much much worse during the period of their incarceration away from home.

There among the lines of identical stones, I found the grave of Wolfgang Rosterg.

Here was the man who’d been murdered at Camp 21; on December 23rd, 1944, just one week after his 35th birthday. Next to him in the same dismal plot, another Camp 21 casualty; Oberleutnant Willy Thorman, who’d been found hanging from a tree just a week before Rosterg’s Christmas killing.

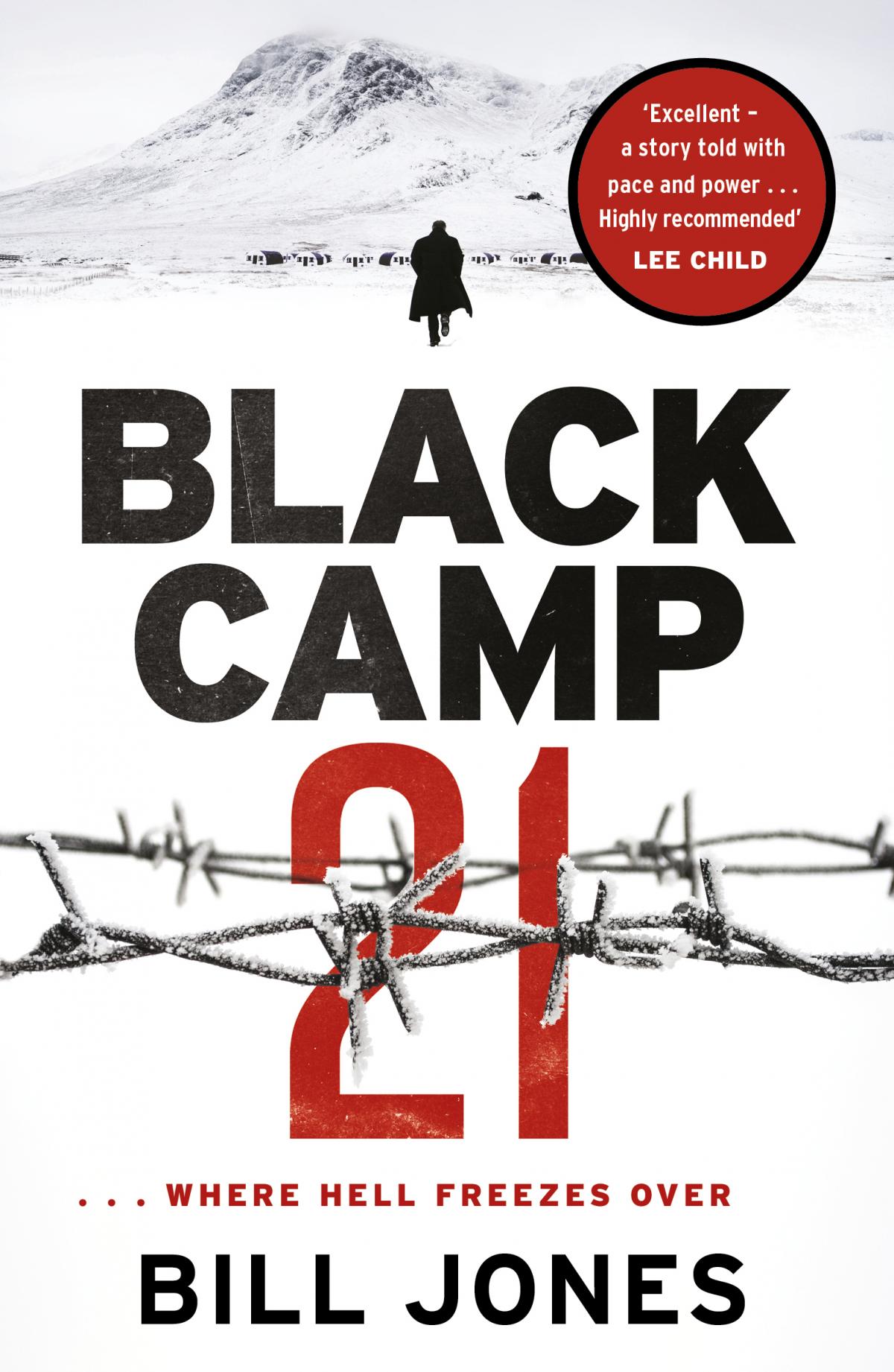

Not Camp 21, I decided then, but Black Camp 21. And not a dry, non-fiction piece of academic research, but a novel; a format that would allow me to create three-dimensional characters from mere names; and fully develop the twisted narrative that climaxed with an innocent man’s horrible death.

At no stage of the process which followed was anything easy. For almost three years, I shared my life with people who mystified me and events which truly shocked me. I was also aware that I was hugely pushing the bounds of literary license; developing characters from the barest of bones whose long ago deaths had robbed them of the right to reply.

Gradually, however, the story came together. Crucially, into the mix of real people I introduced my own key protagonist; Max Hartmann, an empathetic young German soldier torn between his oath to the Fuhrer and his deep love for a bride he scarcely knows and the child he’s never met.

It is Max’s dilemma – his desperate, truncated affair – which lies at the heart of my retelling of this story; a story about friendship, love and the choices men like Max often chose to not to make.

After his capture in Northern France, in August 1944, we follow him as he is shipped back to Britain. Here he is categorised as a ‘black’ prisoner – highly dangerous – forced ever more into the company of men who saw their presence on English soil as an opportunity to extend the war, not end it.

At Devizes Camp (Camp 23), Hartmann is drawn into a delusional conspiracy to break out and march on London, following which he – and the plot’s real leaders – are interrogated, bundled on a train, and dispatched to a place where they can do no more damage.

Camp 21. Black Camp 21. My boyhood Cultybraggan.

For any writer, nothing beats the sensation that one is covering new ground; or covering old ground very differently.

Tell almost anyone that over 400,000 German prisoners lived in Britain for up to four years, and they will be amazed. Tell them there was probably a POW camp in their town and they probably won’t believe you.

Almost every camp was dismantled soon after the war. Only this one – the one at the heart of my story – remains almost exactly as it was. Which, given what took place there, might be considered strange. Even a little macabre.

So what exactly had happened, just two days before Christmas in 1944?

Ever since the Devizes debacle, its ringleaders had been looking for a ‘mole’ and in Wolfgang Rosterg – an older and vocally anti-Hitler fellow-prisoner – they believed they’d found him.

For an entire night, he was beaten, tortured and finally strangled under the gaze of around one hundred men. Among those observers – to his shame and confusion – is my creation, Max Hartmann.

In the end, whose side is he on? At the death, can he find the courage to finally make that choice between what he is and what a system wants him to be?

Whether people read this book or not (and obviously I hope they do!!) I urge everyone to find the time to visit this extraordinary, atmospheric place.

And if you go, try to imagine 4,000 men huddled behind its wire; see if you can ghost up the sound of patriotic German hymns or the cries of ‘Heil Hitler’ as the crows circle in the pine trees, and the sad, lifeless body of Wolfgang Rosterg is carted away under a sheet.

If you do, there might be another wonderful record from that summer of 1968 which suddenly seems appropriate.

Aretha Franklin.

I Say A Little Prayer.

For Wolfgang Rosterg.

Black Camp 21 by Bill Jones is published by Polygon, price £8.99

Why are you making commenting on The Herald only available to subscribers?

It should have been a safe space for informed debate, somewhere for readers to discuss issues around the biggest stories of the day, but all too often the below the line comments on most websites have become bogged down by off-topic discussions and abuse.

heraldscotland.com is tackling this problem by allowing only subscribers to comment.

We are doing this to improve the experience for our loyal readers and we believe it will reduce the ability of trolls and troublemakers, who occasionally find their way onto our site, to abuse our journalists and readers. We also hope it will help the comments section fulfil its promise as a part of Scotland's conversation with itself.

We are lucky at The Herald. We are read by an informed, educated readership who can add their knowledge and insights to our stories.

That is invaluable.

We are making the subscriber-only change to support our valued readers, who tell us they don't want the site cluttered up with irrelevant comments, untruths and abuse.

In the past, the journalist’s job was to collect and distribute information to the audience. Technology means that readers can shape a discussion. We look forward to hearing from you on heraldscotland.com

Comments & Moderation

Readers’ comments: You are personally liable for the content of any comments you upload to this website, so please act responsibly. We do not pre-moderate or monitor readers’ comments appearing on our websites, but we do post-moderate in response to complaints we receive or otherwise when a potential problem comes to our attention. You can make a complaint by using the ‘report this post’ link . We may then apply our discretion under the user terms to amend or delete comments.

Post moderation is undertaken full-time 9am-6pm on weekdays, and on a part-time basis outwith those hours.

Read the rules here