For those girls lucky or wealthy enough to have an education before the 20th century, they were a key element to their schooling. Painstaking, inventive, framed on the wall by a proud family, the sampler, an embroidered swatch of material that first took hold in the 16th century as a means of learning different sewing stitches and designs, was by the 18th century a way of summarising the education, accomplishments and character of the girl who sewed it.

The sampler itself was international, as were the basic elements it contained, from the alphabet which showed that the maker could read, to the stitched symbols of her home town or school. Names, interests, even deaths, rarely, were marked in thread, and the fascinating thing about this Scottish collection, owned entirely by American philanthropist Leslie Durst, is that it covers nearly every one of the old shires of Scotland, from Orkney to Kintyre, with all the attendant regional differences. In this fascinating new exhibition at the National Museum of Scotland, a rare light will be shone on the hidden history of girls and women in the early modern period.

Helen Wyld, Senior Curator of Historic Textiles at the Museum has spent much time researching the project. Wyld’s own specialist research interest is in tapestry, the history of which is necessarily one of aristocratic and royal commissions, of chivalric motifs, of objects which are very much “high art”. To work with the samplers, imbued with an entirely different history and a much wider social milieu was very different – and refreshing, she says.

Wyld spent two weeks in Portland, Oregon, with Durst, going through the collector’s 500-strong Scottish collection. Many of the works, she says, are in good condition, partly a result of their having been cherished, although the very act of framing could sometimes affect the condition of the samplers as backing materials were often acidic.

But if some of the aesthetic has been lost, very much more is laid bare in these fascinating pieces. School in the 18th and 19th centuries was very different from the modern day, says Wyld. “It was not so formal. Middle and upper-class girls might be sent to boarding school. Those in urban areas might go, not just to one school, but to different schools or tutors for different disciplines - there would be a school for sewing, a French Master for language, for example.” School for those in rural areas concentrated on domestic skills and Bible reading – the same for girls in all social strata – as a means of both learning to read and instilling moral values.

“Early on in the 16th and 17th century, it was an aristocratic or upper middle class pursuit,” says Wyld, “But during the 18th century, when education spread in Scotland and Britain, samplers made it further down the social scale as more middle class girls – the children of tradesman and farmers - obtained access to the materials. Samplers were being made in some of the charitable schools, set up to look after the poor children of the lower end of respectable tradesmen’s families.”

Durst, who will bequeath the entire collection to the Museum, has called it her “life’s calling” to give every Scottish sampler maker their life story, carrying out extensive research encouraged by the unique fact that Scottish samplers often contain a lot of genealogical information from extended family – and the fact that Scottish women kept their maiden name after marriage, enabling them to be traced.

Other markers helped, too. “Teachers in different schools might have particular symbols and stitches which they taught, and so you will find similar symbols cropping up in many related samplers,” says Wyld. Location was important too, with the names of the places in which the girls grew up embroidered and, in some cases, local landmarks reimagined - with varying degrees of accuracy and “not always recognisable,” smiles Wyld.

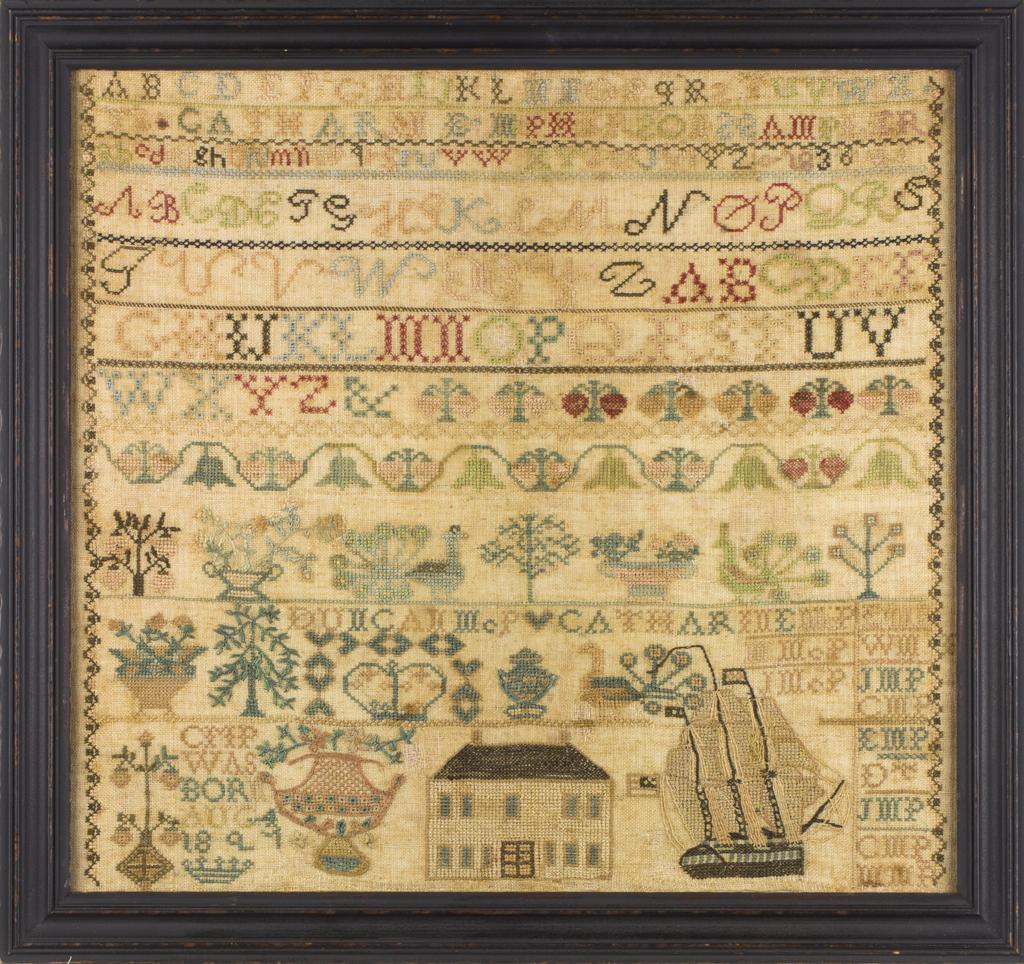

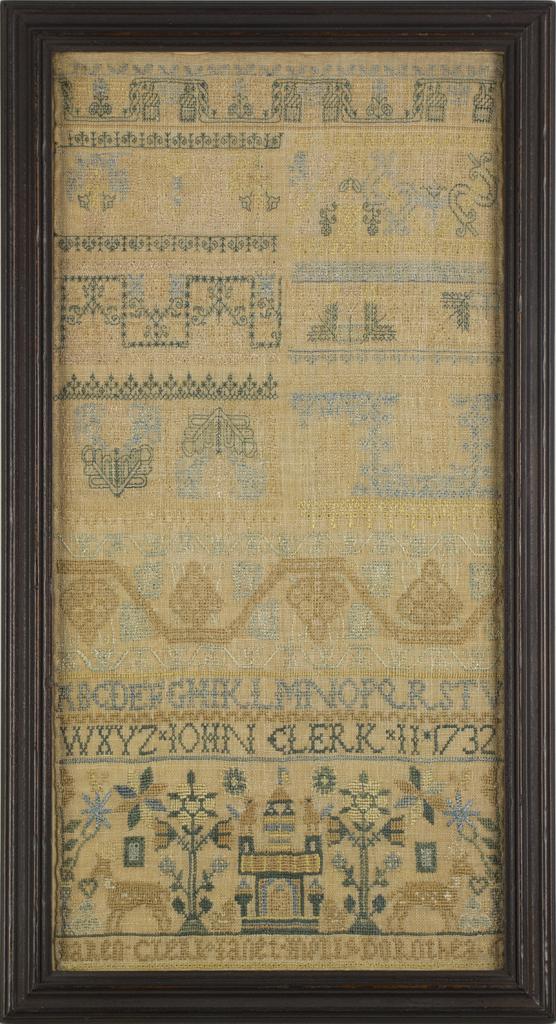

There was the landed Dorothea Clerk of Penicuik, whose uncle was the famous John Clerk of Penicuik (the composer), and who married her cousin when she was just 15 in unusual circumstances. There is the sampler of a Catherine Macpherson, which ostensibly has all the characteristics of a Scottish sampler until you realize that the carefully embroidered ship in the lower right corner has a tiny American flag – the ship being the boat that brought her family to America. Jane Milton, in her intricate and neat sampler, has embroidered the Orphan Hospital of Edinburgh, where she, and her many siblings, were schooled. These are beautiful things in their own right, yet full of signs and symbols, they are also a researcher’s dream.

“I hope that people will realize it’s not just about sewing. It’s about young girls’ lives, women’s lives, a window on the past that can’t be gained from other objects. These are things made by young girls, not by artists. It gives us a completely new perspective on our history.”

Embroidered Stories: Scottish Samplers, National Museum of Scotland, Chambers Street, Edinburgh, 0300 123 6789 www.nms.ac.uk 26 Oct – 21 Apr 2019 Daily 10am – 5pm

Why are you making commenting on The Herald only available to subscribers?

It should have been a safe space for informed debate, somewhere for readers to discuss issues around the biggest stories of the day, but all too often the below the line comments on most websites have become bogged down by off-topic discussions and abuse.

heraldscotland.com is tackling this problem by allowing only subscribers to comment.

We are doing this to improve the experience for our loyal readers and we believe it will reduce the ability of trolls and troublemakers, who occasionally find their way onto our site, to abuse our journalists and readers. We also hope it will help the comments section fulfil its promise as a part of Scotland's conversation with itself.

We are lucky at The Herald. We are read by an informed, educated readership who can add their knowledge and insights to our stories.

That is invaluable.

We are making the subscriber-only change to support our valued readers, who tell us they don't want the site cluttered up with irrelevant comments, untruths and abuse.

In the past, the journalist’s job was to collect and distribute information to the audience. Technology means that readers can shape a discussion. We look forward to hearing from you on heraldscotland.com

Comments & Moderation

Readers’ comments: You are personally liable for the content of any comments you upload to this website, so please act responsibly. We do not pre-moderate or monitor readers’ comments appearing on our websites, but we do post-moderate in response to complaints we receive or otherwise when a potential problem comes to our attention. You can make a complaint by using the ‘report this post’ link . We may then apply our discretion under the user terms to amend or delete comments.

Post moderation is undertaken full-time 9am-6pm on weekdays, and on a part-time basis outwith those hours.

Read the rules here