THERE is a scene in Outlaw King where Robert the Bruce and his rival John "The Red" Comyn stand toe-to-toe inside Greyfriars Kirk in Dumfries having a heated discussion about the fate of William Wallace, who has been hanged, drawn and quartered on the orders of Edward I.

"Wallace got what he deserved," barks Comyn. "He wasn't a man. He was an idea. A destructive and dangerous idea." It is a powerful moment: a line in the sand separating where the narrative of Wallace ends and that of Bruce begins.

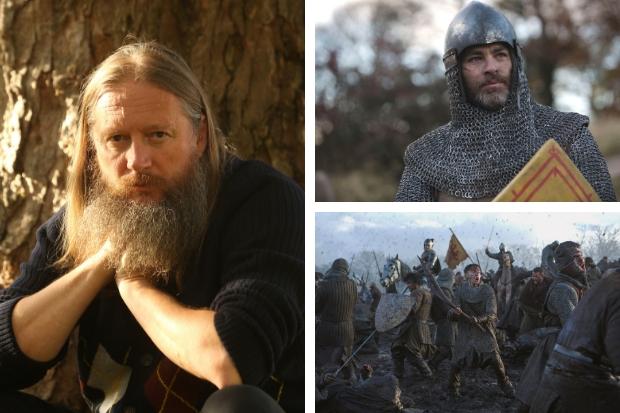

Director David Mackenzie was conscious of making that distinction. "The shadow of Wallace has got to be there in that story," he says. "But this is not the William Wallace show – this is the Robert the Bruce show. We had to touch on it, deal with it and move on."

The idea of making a film about the King of Scots has occupied Mackenzie's thoughts for some years. It was shelved as he embarked upon other projects – most notably the Oscar-nominated neo-Western crime thriller Hell or High Water – before being greenlit by online streaming giant Netflix.

The big-budget biopic, starring Hollywood star Chris Pine as the eponymous hero, is released on Friday. Mackenzie, 52, is sanguine when asked what first drew him to Bruce.

"Robert the Bruce is a Scottish national hero and I grew up with these stories of him," he says. "I was desperate to make a heroic movie set in Scotland and it feels like the story of Robert the Bruce has been eclipsed by William Wallace after Braveheart. I tried not to talk about that subject because I want this to be a totally different film. But I have realised that I can't avoid talking about it.

"There is a slight sense of wrongs to be righted in that the guy who achieved the goals that Wallace was trying to achieve – but didn't – seems to have got lost in the heroic failure of war. Which is in its own right a slightly Scottish trait to glorify heroic failures."

Although that is not to airbrush Wallace entirely. Mackenzie, who co-wrote the £85 million Outlaw King, acknowledges how the wave of anger and growing unrest over Wallace's execution saw Bruce seize upon the opportunity to stake his claim to the Scottish throne.

"Suddenly he [Edward I] started distributing bits of William Wallace's body all over the country," says Mackenzie. "It did get a fever burning." When it comes to making a film about Bruce, says Mackenzie, one of the biggest challenges was where to take up his story and when to end it.

"Robert himself didn't achieve his aims until he was almost dying," he explains. "There is no kind of glorious moment where it happens."

At its heart, Outlaw King charts the pivotal 15-month period from early 1306, when Bruce launches his campaign to become king after stabbing Comyn, through his defeat at the Battle of Methven later that year, time spent in exile and subsequent landmark victory over the English army at the 1307 Battle of Loudoun Hill.

For Mackenzie, one of the watershed moments was the death of Bruce's father in 1304. "I think his father's death is underplayed in history as being a moment when Robert was able to step out from the patriarchal shadow," he says.

"Going from that moment to the death of John Comyn then into the coronation, the attack at Methven and being taken right to the far ends of the country. It all happens really quickly. Suddenly there is this incredibly dramatic period.

"It felt like there was some real pace in that. The survival stakes and having to pull yourself back from deep down. I felt like that was a strong part of Robert's narrative and so we focused on that.

"There is a lot of story to tell. We had to control the beginning and slow things at the end in order to be as faithful as possible with the middle."

Mackenzie and Pine previously worked together on Hell or High Water. How does he rate the actor's portrayal of Bruce? "I'm delighted with Chris," he enthuses. "He really embraced it and threw himself into the physicality of the role as that troubled hero. He has done a great job."

Aaron Taylor-Johnson plays James Douglas, with Florence Pugh as Bruce's second wife Elizabeth de Burgh alongside a raft of Scottish names, including Tony Curran, James Cosmo, Gilly Gilchrist, Steven Cree and Alastair Mackenzie (yup, the surname is no coincidence – they are brothers).

"We've got Gavin Mitchell in there," adds Mackenzie, referencing a scene in Bruce's camp before the Battle of Methven that features the actor best known as Boabby the Barman in Still Game.

The big star is Scotland itself. Among the many locations used for filming were Linlithgow Palace, St Michael's Parish Church and Blackness Castle in West Lothian, Borthwick Castle, Doune Castle, Craigmillar Castle, Dunfermline Abbey and Glasgow Cathedral.

Scenes were also shot on Skye – the Coral Beach, Talisker Bay and the Quiraing – as well as in Glencoe, Aviemore, Loch Lomond, Gargunnock, Muiravonside Country Park near Falkirk, Seacliff Beach in East Lothian and the University of Glasgow.

Its cast, including 400 extras, converged on Mugdock Country Park near Milngavie to film the Battle of Loudoun Hill. The Northumbrian border at Berwick-upon-Tweed also features. "We shot entirely in Scotland apart from Berwick-upon-Tweed," says Mackenzie.

"James Douglas captured Berwick-upon-Tweed in 1318 and it became Scottish again in the long wrangle between England and Scotland. I say: 'Filmed entirely in Scotland according to the borders of 1320'."

It felt important to Mackenzie that Outlaw King was shot here although, he admits, there was a fear that, if the stars hadn't aligned, that might not have happened.

"The other alternative was thinking if the timing wasn't right with the time of year, we would have had ended up having to go to New Zealand or somewhere like that. But that was only a vague plan B and never a popular option. I think it would be crazy to shoot anywhere but Scotland.

"We were really lucky with the weather window from late summer into late autumn. It is always a great time of year and I was keen to shoot then."

Didn't that mean having to brave the midges, though? "We had two weeks of midges and they were very full-on," he says. "That was a small price to pay."

Now that the film is shot, edited and ready for release, Mackenzie feels vindicated in his belief that only the canvas of Scotland would do.

"It is a film about someone who fought for a land – that land is part of the spirit and soul of Bruce. It was what gave him shelter and allowed him to do what he did. The clear example is that battle at the end where he uses the land to his advantage."

Outlaw King opened the Toronto International Film Festival in September and had its Scottish premiere in Edinburgh last month. Mackenzie trimmed 20 minutes from the version shown in Toronto – taking it to around two hours – following audience feedback.

"There was a length thing," he says. "There were two narratives and cul-de-sacs that I wasn't sure about and I got rid of those. I think the flow is much better now.

"The things I cut out were things that I liked and looked good on the showreel, so it wasn't easy, but for the sake of the experience of the film I am very happy with the way it is now. This is the definitive version of the film."

Why does he see it as important to share the story of Bruce with modern audiences? "It is a 700-year-old story," says Mackenzie. "It is a story that hasn't properly been told. The reason for telling it today is because I have a chance to make it today.

"It is quite hard to start thinking about contemporary parallels because there is nothing I am particularly trying to say that is a contemporary parallel."

Could there be those who see it, like Braveheart, as a rallying cry? "We try to tell the story from an apolitical standpoint," asserts Mackenzie. "Everybody in Scotland – whatever their beliefs – can connect with it. I don't want to be drawn into that one."

This isn't the first time that Bruce's story has been told on screen. The Bruce (1996) saw the leading man portrayed by Sandy Welch, while Angus Macfadyen took up the role in Braveheart (1995).

"I have never seen The Bruce," says Mackenzie. "Obviously I have seen Braveheart but not for a long time and when I did see it it felt really dated – quite blood and soil."

The eldest of three children, Mackenzie was born into a Scots family in Northumberland. His late father was Royal Navy Rear Admiral John Mackenzie, from Perth, while his late mother Ursula was a chef who hailed from Dundee.

It was in his teens that Mackenzie fell in love with film. "I had a moment when I was 18 where I became quite addicted to going to the movies – I would go pretty much every day," he recalls.

"I started off doing photography and graduated into movies. I studied it and had a job in a rep cinema in London where you got comp tickets to all the other arthouse cinemas. I was able to educate myself in film and that was a huge part of it for me."

He and his brother ended up in the same industry – Monarch of the Glen and Borgen actor Alastair in front of the camera and David behind it. Is it nice to be able to share that adventure?

"It is fun when it happens," he says. "I was really pleased that Al was able to take a part in this film. It is great when we can work together and hang out."

Besides, he gets to boss his younger brother about, right? Mackenzie laughs. "It is the only chance I ever get to tell him what to do," he jokes. "I'm not a bossy director, that is not the way I roll."

Mackenzie is based in Glasgow ("whenever I get a chance to go home," he adds) where he lives with his partner Hazel Mall and their three children.

He co-founded the production company Sigma Films (which has its headquarters at Film City Glasgow in Govan) with brother Alastair and Gillian Berrie in 1996.

His CV includes The Last Great Wilderness, Young Adam, Asylum and Hallam Foe. Mackenzie relished the opportunity to work on home turf and admits to being spoiled for choice when recounting his favourite moments making Outlaw King.

"Going to Skye and filming at Talisker Bay and the Coral Beach, that was amazingly beautiful," he says. "We were blessed with the weather. On Skye we had two days when we were in boats and the wind was blowing in the right direction both days."

Another highlight was epic scenes re-enacting the Battle of Loudoun Hill. "The intensity of the final battle which we filmed at Mugdock Country Park just outside Glasgow, the mud and mayhem and scale of that, trying to represent medieval warfare which was very blunt and horrible," he says.

"Everyone combining together, our amazing stunt guys, all the actors in the mud throwing themselves at it. The sun was going down over us and creating those incredible colours in the middle of all this mayhem. That was pretty special."

Many viewers may be surprised not to see the 1314 Battle of Bannockburn featured in Outlaw King. There is good reason for that, says Mackenzie.

"Loudoun Hill was a major turning point and a kind of rehearsal for Bannockburn. But it [Bannockburn] was eight years later in a totally different timeframe. In a way, if we ever get to make the sequel, we can do that. It is enough of a story to have that one battle [Loudoun Hill] and it is intense enough on its own terms. It just felt like the right thing to do."

Does Mackenzie think his film might change people's views of Bruce – even just to come away from watching it knowing a little more about the story?

"It demythologises in some way and informs in another way," he says. "You get a clearer picture of who Robert was and can maybe then read a couple of history books to get to know even more about it. We obviously can't cover everything about him and it is a work of drama – it isn't a work of history."

While he alludes that the point in Bruce's story where Outlaw King finishes gives scope for a sequel, Mackenzie is reluctant to be drawn on that. "This has been a long journey to get it this far and I'm not thinking about a sequel right now," he chuckles. "But, obviously, the story does continue."

Outlaw King is released globally on Netflix from Friday (November 9) with a limited cinema release

Why are you making commenting on The Herald only available to subscribers?

It should have been a safe space for informed debate, somewhere for readers to discuss issues around the biggest stories of the day, but all too often the below the line comments on most websites have become bogged down by off-topic discussions and abuse.

heraldscotland.com is tackling this problem by allowing only subscribers to comment.

We are doing this to improve the experience for our loyal readers and we believe it will reduce the ability of trolls and troublemakers, who occasionally find their way onto our site, to abuse our journalists and readers. We also hope it will help the comments section fulfil its promise as a part of Scotland's conversation with itself.

We are lucky at The Herald. We are read by an informed, educated readership who can add their knowledge and insights to our stories.

That is invaluable.

We are making the subscriber-only change to support our valued readers, who tell us they don't want the site cluttered up with irrelevant comments, untruths and abuse.

In the past, the journalist’s job was to collect and distribute information to the audience. Technology means that readers can shape a discussion. We look forward to hearing from you on heraldscotland.com

Comments & Moderation

Readers’ comments: You are personally liable for the content of any comments you upload to this website, so please act responsibly. We do not pre-moderate or monitor readers’ comments appearing on our websites, but we do post-moderate in response to complaints we receive or otherwise when a potential problem comes to our attention. You can make a complaint by using the ‘report this post’ link . We may then apply our discretion under the user terms to amend or delete comments.

Post moderation is undertaken full-time 9am-6pm on weekdays, and on a part-time basis outwith those hours.

Read the rules here