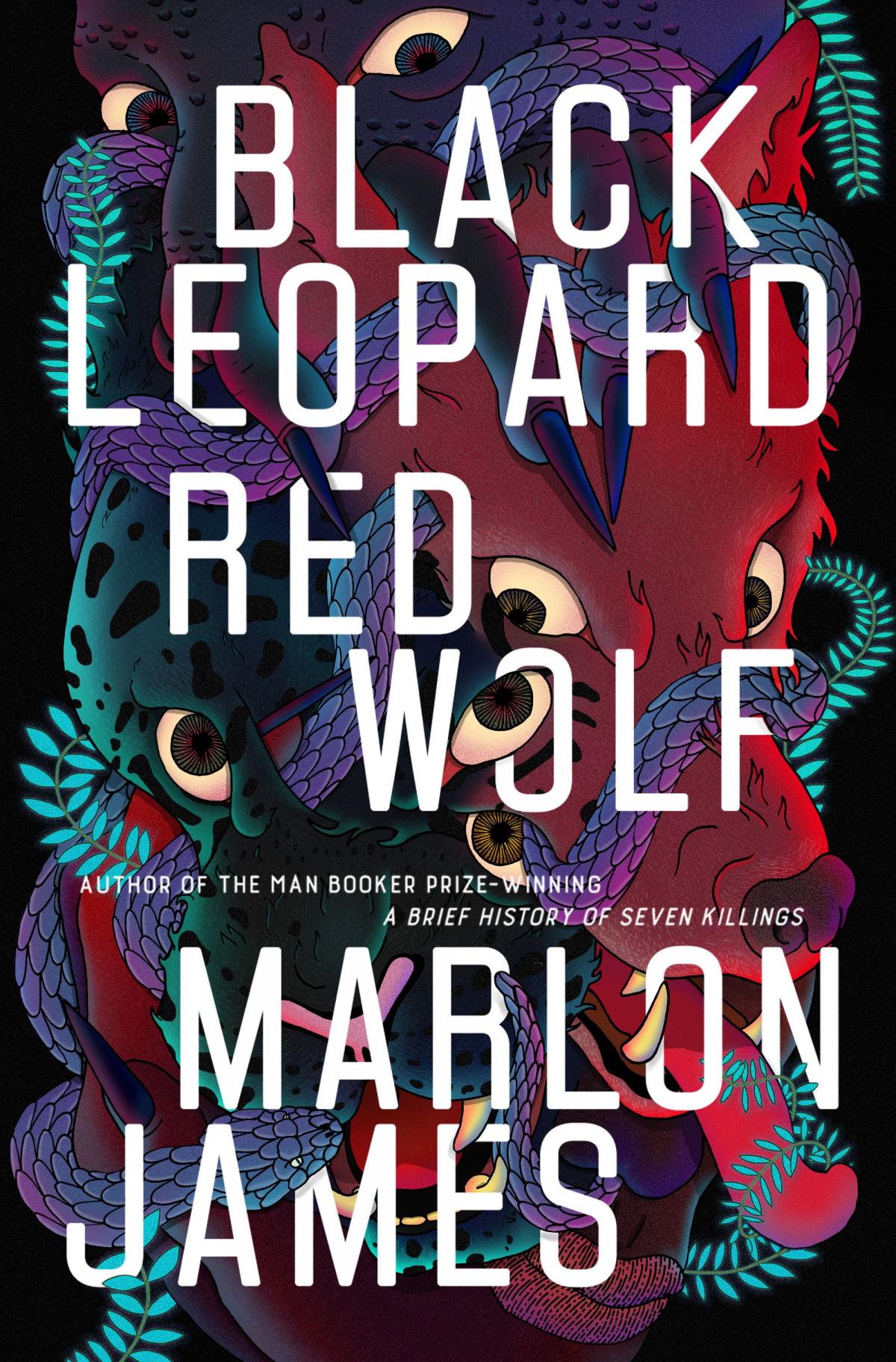

Black Leopard, Red Wolf by Marlon James (Hamish Hamilton, £20)

THE DEBATE that surrounds the sort of writing that can win the Man Booker Prize each year has veered between questions of genre and questions of accessibility. In 2010 Howard Jacobson’s The Finkler Question was acclaimed as singular recognition of the comic novel, at least since Kinsley Amis in 1986, which rather overlooked the humour in DCB Pierre’s Vernon God Little. Last year Anna Burns’s Milkman won the 50th prize against a background of the chairman of the judges, Kwame Anthony Appiah, promoting it as a “difficult” read.

In some ways, but possibly not by intent, the book with which Marlon James follows-up his 2015 Booker-winner, A Brief History of Seven Killings, addresses these questions head on. Alongside romantic and historical fiction, fantasy is beyond argument one of the most popular genres on the bookshelves. In JK Rowling’s Harry Potter it continues to shift units in record-setting quantity. Thanks in part to the recent film adaptations, Tolkien has moved from being a junior rite-of-passage read towards the mainstream. Glasgow University now offers a popular post-graduate M Litt course in fantasy. Unless you allow Yann Martel’s Life of Pi, however, it is missing from the list of Booker winners.

The ambition of Black Leopard, Red Wolf is beyond question. Announced as the first volume of the “Dark Star Trilogy”, it is in itself a big book and one that is at considerable pains to create its own unique world. It is a landscape that is recognisably African and ancient, or at least entirely without the trappings and technology of the modern world, closer to nature and armed with weapons that cut, pierce and club. The species that inhabit it morph between animal and human, have magical properties and mystical talents. When they suffer and die it may not necessarily be for ever. And, of course, there is a quest, through challenging geographies and necessitating many victories in battle.

But reading it can often be a bit of a slog, to be frank. Compared to the challenge of contemporary Irish fiction that embraces the heritage of James Joyce, there is nothing very syntactically complex going on on the page, but as our protagonist, Tracker, goes at it again with his axes it can be hard to work up much enthusiasm for the outcome of the fight. There is often a sense of the comic book about the violence, not in the sense of it being less than entirely serious – it is often gory and explicit – but in the detail of the description trying to compete with graphic depiction. Here is a passage from near the end of the book:

“He kicked the first guard in the balls, jumped on him when he fell, leaped at two other guards, knocked away their spears with his left sword, and sliced one in the belly with the right sword and chopped the other in the shoulder. But hark, his back burst with blood and the guard who slashed him charged.”

And so it goes on. That “But hark”, incidentally, is not unusual in little asides that try to place the work in a long tradition of ancient storytelling, but which sits alongside echoes of rather more contemporary narratives.

Tracker, whose prime asset is a bloodhound’s nose, is on the trail of a boy on whose existence pivots the patriarchal or matriarchal continuance of the royal line, the former having usurped the latter. There is a well-rendered visit to an ancient library, shortly before its destruction, that holds secrets about the lineage because “when woman and man write words, they dare to look at the divine.”

But for every mention of following a star (page 206), there may be cited the image of people falling from burning towers (page 457). The world James is creating is full of modernity and that is particularly true of the personal relationships in the story.

Alongside the violence there is a great deal of sex, and particularly homo-eroticism. It moves from very basic lust-fulfilment (James has created his own lexicon of genitalia and bodyparts for the purpose but it is never opaque what is happening) to the startlingly coy: “He blew on my navel, then moved lower between my legs and did precious art. I begged him to stop in the most feeble whisper.”

Only twenty pages before that, however, there is some of the most genuinely challenging reading in the book, with a three page sentence that replays some of the narrative in reverse, and might indeed have been inspired by Finnegans Wake. Other passages owe an obvious debt to 20th century thriller or detective writing, and elsewhere the dialogue (and there is a great deal of that) waxes very philosophical.

On the evidence of this first volume, James has embarked on a bold undertaking: placing a very 21st century attitude to how we relate tolerantly to one another as men and women within a brutal mythic world as a way of suggesting that this is how human lives should always have been lived. The practical question to ask is how many readers will have patience with his method

Why are you making commenting on The Herald only available to subscribers?

It should have been a safe space for informed debate, somewhere for readers to discuss issues around the biggest stories of the day, but all too often the below the line comments on most websites have become bogged down by off-topic discussions and abuse.

heraldscotland.com is tackling this problem by allowing only subscribers to comment.

We are doing this to improve the experience for our loyal readers and we believe it will reduce the ability of trolls and troublemakers, who occasionally find their way onto our site, to abuse our journalists and readers. We also hope it will help the comments section fulfil its promise as a part of Scotland's conversation with itself.

We are lucky at The Herald. We are read by an informed, educated readership who can add their knowledge and insights to our stories.

That is invaluable.

We are making the subscriber-only change to support our valued readers, who tell us they don't want the site cluttered up with irrelevant comments, untruths and abuse.

In the past, the journalist’s job was to collect and distribute information to the audience. Technology means that readers can shape a discussion. We look forward to hearing from you on heraldscotland.com

Comments & Moderation

Readers’ comments: You are personally liable for the content of any comments you upload to this website, so please act responsibly. We do not pre-moderate or monitor readers’ comments appearing on our websites, but we do post-moderate in response to complaints we receive or otherwise when a potential problem comes to our attention. You can make a complaint by using the ‘report this post’ link . We may then apply our discretion under the user terms to amend or delete comments.

Post moderation is undertaken full-time 9am-6pm on weekdays, and on a part-time basis outwith those hours.

Read the rules here