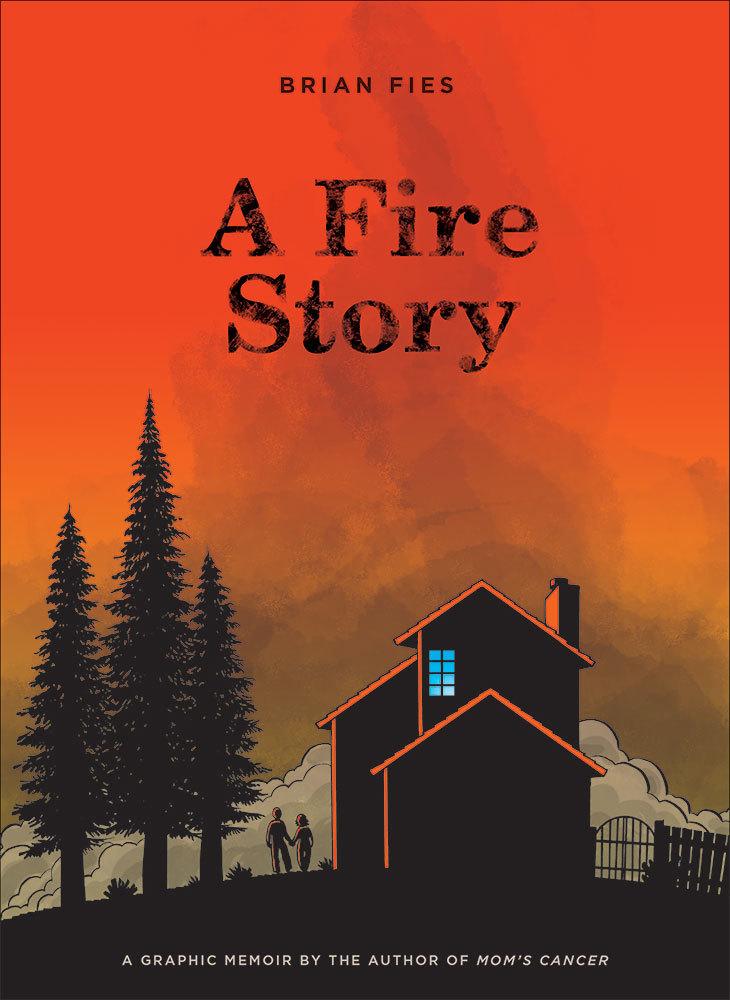

Eisner award-winning cartoonist Brian Fies’s new graphic novel A Fire Story is his account of the 2017 blaze that destroyed his northern Californian home and the impact that terrible experience had on him and his neighbours. It’s an honest, powerful, clear-eyed account of the events of that night and the ongoing legacy of the destruction it caused.

Here, Fies talks about turning his experiences into graphic novel form.

Brian, in a nutshell, what happened?

When my wife, Karen, and I went to bed the night of October 8, 2017, we weren’t worried about a small fire 20 miles away. Three hours later, that small fire was fanned by hurricane force winds into what I call in my book “a napalm tsunami” that stormed through the hills. Separate fires that followed similar paths that night combined to destroy more than 6,000 homes and become the most destructive California wildfire in history—a record that, unfortunately, lasted only a year. Karen and I fled with about 15 minutes’ warning. We managed to throw a few precious things into the car: pets, important papers, some family photos. Everything else was destroyed.

When did you first realise quite how bad things were? Were you scared?

The night we evacuated, we had no sense of the wildfire’s scale. All we saw was an orange glow in the sky. I couldn’t conceive how that distant glow could get into my neighbourhood. I thought surely firefighters would come and form a protective line, not realising that they were completely overwhelmed fighting a firestorm on a 40-mile front and that no help was coming. This fire did things I didn’t know fire could do. It flowed like water. It made its own weather. But we didn’t know any of that when we left our home. By the time we knew enough about our situation to be scared, it was many hours later and we were safely out of it.

What was the thing that most struck you when you finally got back to the site of your house?

I walked back into our neighbourhood about 8am the next morning, only five or six hours after the fire swept through. On my way, I passed through blocks of homes completely untouched. I expected mine to look the same. Then I turned a corner onto a smouldering plain that looked like an atomic bomb had hit it, flat and grey as far as I could see. What really struck me, and I was conscious of this at the time, was that my brain couldn’t quite process what my eyes were seeing. Houses and trees seem so permanent, but in a few hours they’d all vanished, like some spectacular magician’s trick. It made no sense. Until I stood directly in front of my destroyed home, I still held a bit of hope that somehow it had survived. I was just numb, but I knew I was numb, and also knew this was a story I needed to tell.

You were writing and drawing about the experience almost immediately. What did that give you?

My wife said the same thing she said when I’d told her I was making my first graphic novel, Mom’s Cancer, which was, “Well, I guess it’ll be good therapy for you.” She might be right. To write about something you’ve got to research it, understand it, and also know yourself enough to understand your reaction to it. It’s difficult. Even while I was dealing with my home and neighbourhood being wiped from the Earth, I felt like I had another pair of eyes floating over my shoulder and taking notes.

My first job out of university was as a newspaper reporter, and I felt compelled to bear witness to this extraordinary event I was in the middle of. I didn’t really have a choice. Making A Fire Story felt like doing journalism. At the same time, I think making a comic gave me an illusion of control over a situation that was very much out of my control. I couldn’t fight the fire, but the world I create on the page is all mine. I think I found some security and purpose in that.

Read More: James Sturm on Donald Trump

Read More: Rachael Ball on her new graphic nvovel Wolf

The graphic novel obviously goes beyond your own experiences. What was your goal?

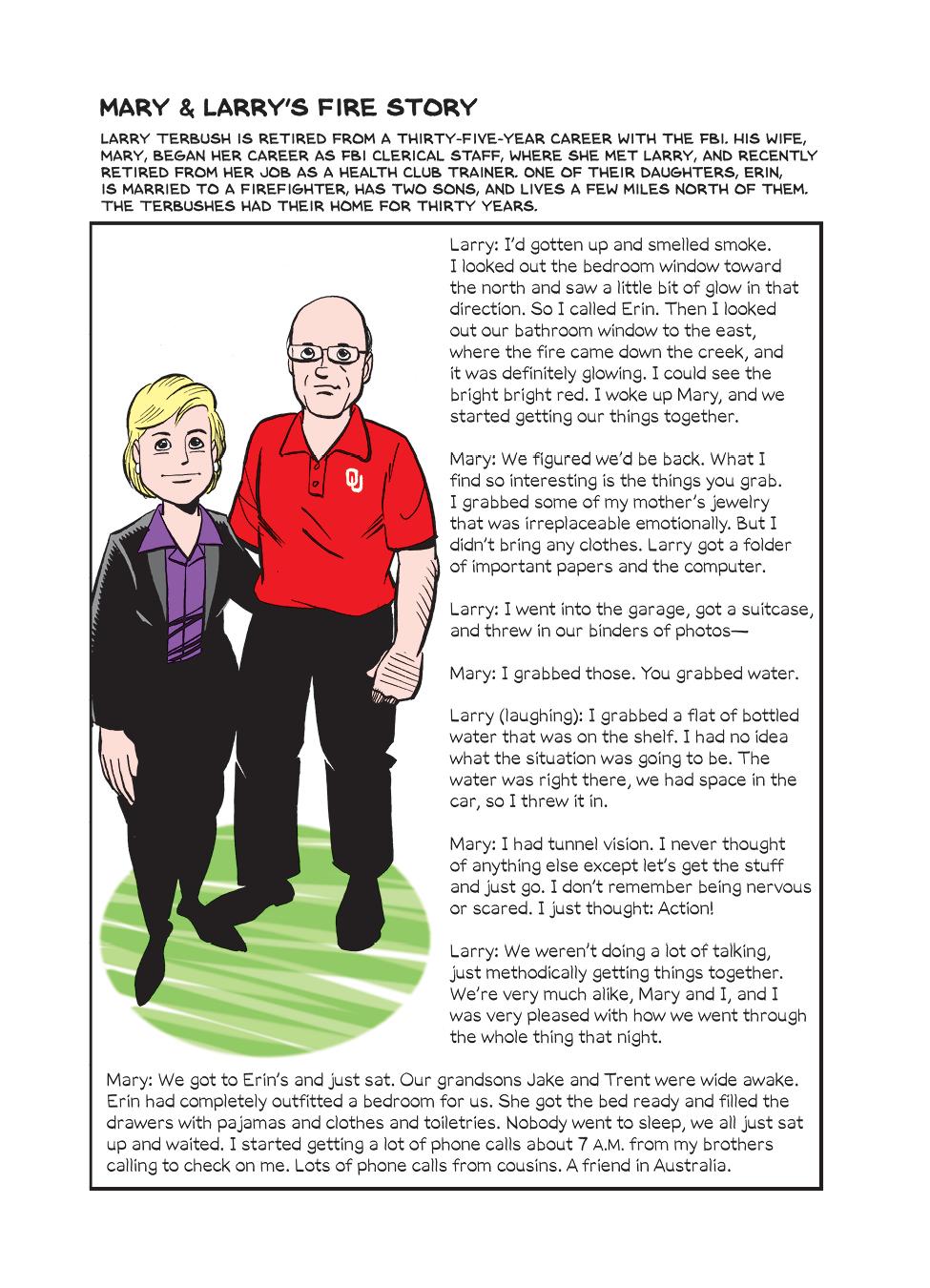

My first draft of A Fire Story, the 18 pages I posted online days after the fire, focused on me and my family. For the graphic novel, I wanted to expand the story in both time and scope. I write in the book about living in a tiny bubble of your own insurmountable problems, then gradually realizing that everyone else has their own bubbles, with problems often worse than yours. Thousands of people, tens of thousands.

It was important that the book kind of lift its eyes and take a broader look around, just as we ourselves did over time. To that end, the book includes interviews with six people telling their own fire stories in their own words, some of them very different from mine. I also tried to put the fire in a larger context of geography, climate change, and so on. I really wanted A Fire Story to stand as a thorough, respectable piece of first-person journalism.

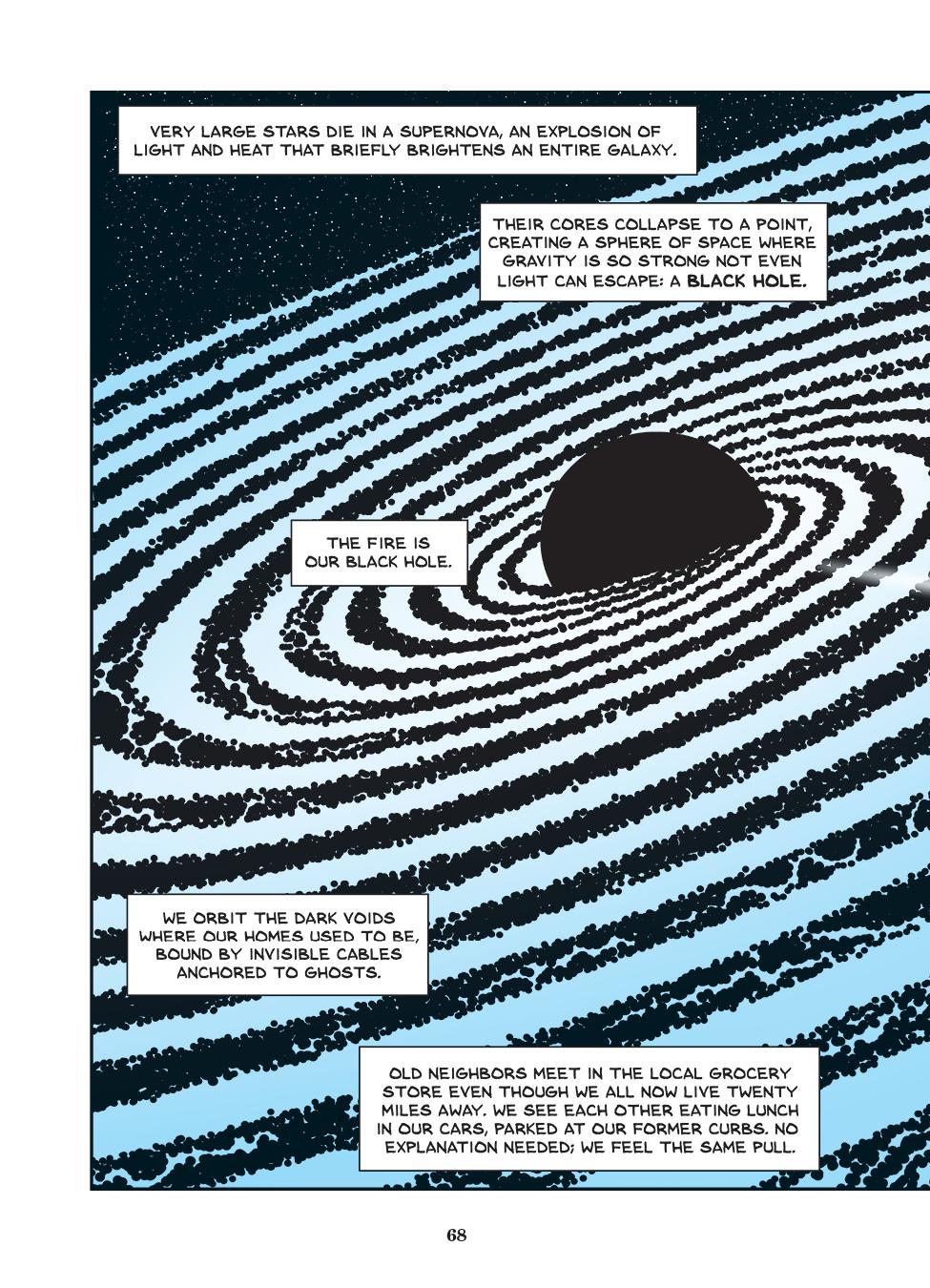

What has been the long-term impact of the fire on you materially and emotionally?

Materially, we’ve been luckier than many. We had money in the bank, and other resources. We had homeowners insurance, though not enough. We’re rebuilding. We’re living very light these days ¬- not a lot of possessions, though I just noticed yesterday I’ve begun to accumulate quite a few books! The few things we managed to save from the fire are precious beyond measure. The things we’ve gotten since the fire don’t mean as much because we have no history with them. Karen and I find ourselves buying one quality item rather than 10 shoddy ones.

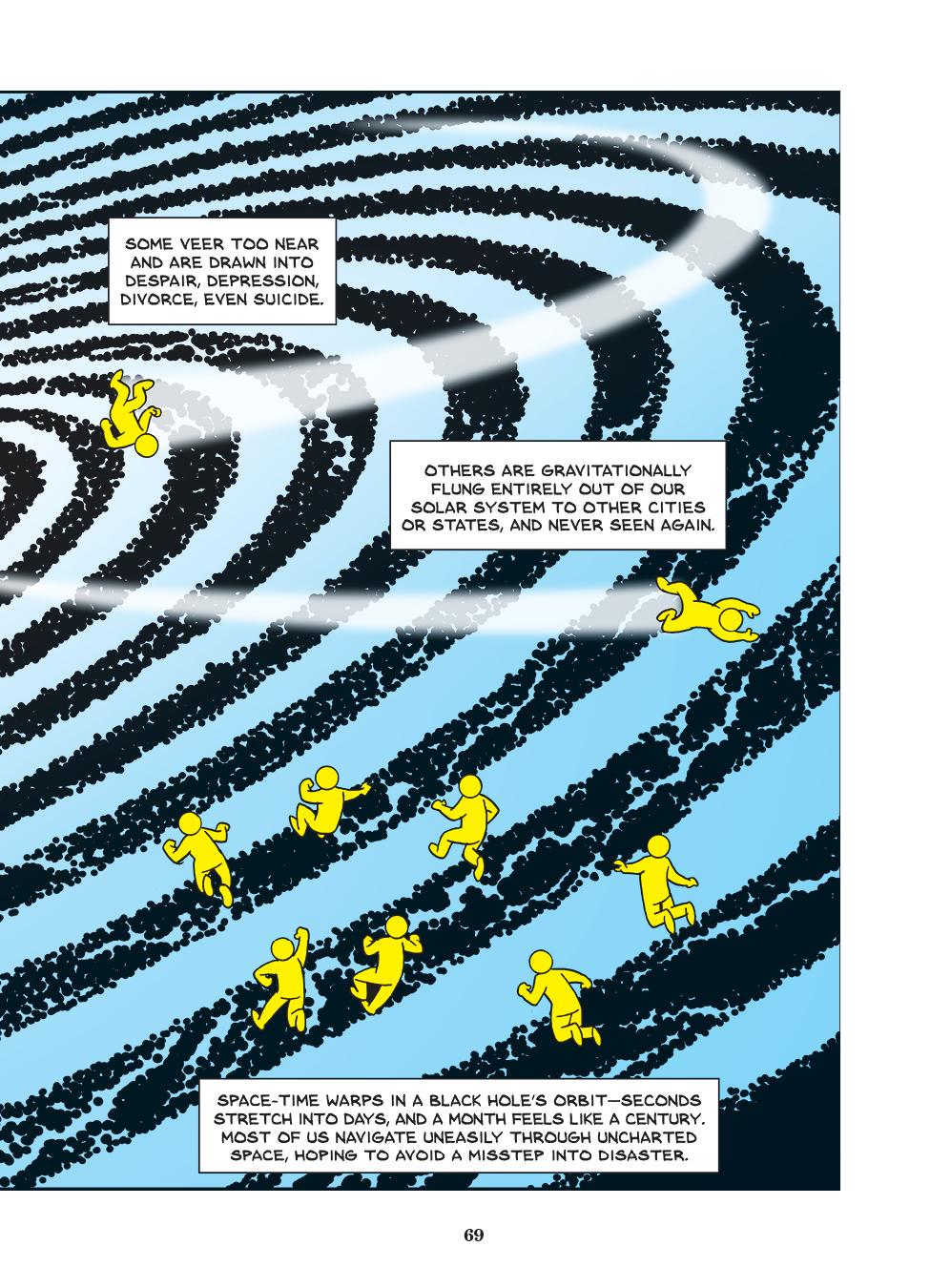

Emotionally, I don’t know if I can say. Maybe in 10 years. A year and a half after the fire, I’m not deeply grieving, although I know people who still are. Most of the time I’d say I’m melancholy. I think I’m both more patient and more demanding; I don’t sweat the small stuff, but I’m dogged on the big stuff. My wife and I get moody, though luckily rarely at the same time, so we can help lift each other’s spirits. Of course we have the usual joy and sadness. My life is split into “before the fire” and “after the fire,” and I think that’ll be true as long as I live.

Your line in the book about how the stuff we own is a marker of time and memory is so true. What do you feel you have lost?

I’ve always had a sense of being a sort of steward of history, if that’s not too pretentious. Old family possessions had come to me, and it was my job to take care of them and pass them down. Well, I certainly botched that job! The losses that mean the most are those connected to sentiment and memories. My late mother’s handwritten notes, a Second World War cap from my grandfather, videotapes of our grown daughters as babies. My kids will never be able to hold those things and tell stories about them. That continuity ended. So we start a new one.

At the same time, is there anything you feel you’ve gained?

Again, ask me in 10 years. I really resist people’s understandable urge to find some uplifting message or a lesson learned in situations like this. Thousands of buildings destroyed, dozens of lives lost—nothing I might gain could be worth it. I did learn something about my character and my wife’s. My daughters really came through. I think our family was tested and emerged stronger. I’m building a nice new house, I got to publish another book that’s already gotten some flattering attention. That’s nice. I’d also trade it all in a second for my home and life before the fire.

What have you learned about yourself through all this?

Primarily that I could get through something like this. I’d never really been tested—never been in combat, never faced a staggering tragedy beyond the usual losses that come with time. Well, now I’ve been tested. I think I passed. As I say in the book, concepts like family, community, tradition and home mean more to me than they used to. I’m more sentimental. I suspect my daughters are tired of me telling them how much I love them.

How is the new house going? Were you not tempted to move elsewhere?

Karen and I never really considered moving elsewhere. We love our neighbourhood, and most of our neighbours said they were coming back, too. We couldn’t think of anywhere we’d rather be. That said, if we were much older, or had fully realized the frustrating, expensive, exhausting process ahead of us, we might have left. Rebuilding a community digging out from a disaster is a unique challenge, and we soon realized even the so-called experts didn’t really know what they were doing.

We did get as quick a start as we could, because we knew there’d be thousands of people behind us. If all goes according to plan, we’ll be in our new house, at the same site as our old one, in early spring, which is sooner than most people in the area. It’ll be a nice house. We’ll see how long it takes to feel like home.

How do you think this experience will impact on your work going forwards?

That may be another “ask me in 10 years” question. At the time of the fire, I was working on two big comics projects. Now, after the fire, and after doing A Fire Story, I may go back to one of them but let the other one go. I’m a different writer and cartoonist now, with a different approach to my work that’s hard to describe. But the one I’ll probably drop just doesn’t feel right anymore. A graphic novel’s not worth the time and effort it take to do if you’re not utterly passionate about it.

What do you love most about comics?

It’s such a unique medium, with such low barriers to entry. For the cost of paper and pen, you too can be a professional cartoonist! I often compare a comic to a popular song: if you just listen to the music, it’s three repetitive chords; if you just read the lyrics, it’s bad poetry. But when you put the music and lyrics together, you’ve got a song that can relive a teenage heartbreak or capture the mood of a generation.

Comics are likewise greater than the sum of their words plus pictures. When a comic is working right, it can feel like a direct tap from its creator’s mind into a reader’s heart. No other medium does that. It’s very powerful to see it happen or experience it yourself.

A Fire Story by Brian Fies is published by Abrams ComicArts, priced £17.99.

Why are you making commenting on The Herald only available to subscribers?

It should have been a safe space for informed debate, somewhere for readers to discuss issues around the biggest stories of the day, but all too often the below the line comments on most websites have become bogged down by off-topic discussions and abuse.

heraldscotland.com is tackling this problem by allowing only subscribers to comment.

We are doing this to improve the experience for our loyal readers and we believe it will reduce the ability of trolls and troublemakers, who occasionally find their way onto our site, to abuse our journalists and readers. We also hope it will help the comments section fulfil its promise as a part of Scotland's conversation with itself.

We are lucky at The Herald. We are read by an informed, educated readership who can add their knowledge and insights to our stories.

That is invaluable.

We are making the subscriber-only change to support our valued readers, who tell us they don't want the site cluttered up with irrelevant comments, untruths and abuse.

In the past, the journalist’s job was to collect and distribute information to the audience. Technology means that readers can shape a discussion. We look forward to hearing from you on heraldscotland.com

Comments & Moderation

Readers’ comments: You are personally liable for the content of any comments you upload to this website, so please act responsibly. We do not pre-moderate or monitor readers’ comments appearing on our websites, but we do post-moderate in response to complaints we receive or otherwise when a potential problem comes to our attention. You can make a complaint by using the ‘report this post’ link . We may then apply our discretion under the user terms to amend or delete comments.

Post moderation is undertaken full-time 9am-6pm on weekdays, and on a part-time basis outwith those hours.

Read the rules here