GENOA, ITALY. MARCH 1941

Carlo Contini, aged 15 years old, has been rounded up by the Gestapo and sent from his home in Naples to the ammunition factories in Genoa.

On the day of Carlo’s departure, his family cried all day. From first light, when they all got up to watch him dress, till they saw fading out of view, waving as the train carried him away, they cried till their tears ran dry. And still they cried. Carlo had never been away from home, not even for a night.

How could they bear for him to be taken away.

Arriving on platform 2 of the Stazione Piazza Principe, in Genoa, Carlo was overwhelmed. The building was quite magnificent. He felt he had arrived in a cathedral with its wide staccato floors, immense marble columns and vast cupola directing shafts of light streaming down on the busy platforms. It was very crowded and noisy. Trains were continuously screeching into the station, every inch of the space on board packed with people; families, children, vagrants, soldiers; passengers crammed in the aisles, leaning out of the windows.

He noticed young boys, even younger than him, precariously clinging to the roofs of carriages, lying flat to avoid overhead wires, They jumped down just before the train stopped and disappeared into the crowd, the guards running after them, hopelessly blowing their whistles. The crowds spilling from the carriages caused so much confusion there was no hope of apprehending anyone.

The platforms were jammed with people, pushing against each other, aggressive, agitated. He tried to stay close to his group. He had met his new friends, Egidio and Angelo, at the factory. They were the same age as him and just as disoriented. They were nineteen in all, all under sixteen years old. None had travelled before, nor left the small towns or villages they came from. They tried to stay in line. A platoon of German soldiers marched past, disciplined, regimented, and pushing them against the wall. Without hesitation, civilians and guards stood aside, like the parting of the Red Sea. No one was arguing.

So this was Genoa. Carlo felt foreign, alien. This was a completely different country; a different world.

‘Madonna,’ he thought, ‘I’m an immigrant.’

The station smelled peculiar; steam, coal and oil mixed with the stench of urine, sawdust and cigarette smoke. It was full of voices and noise, whistles, commands, marching, embracing and kissing. Life was raw in this mayhem; people were grasping at every second.

Italian soldiers stood around, smoking, laughing, looking distracted and bored.

Carlo couldn’t understand. ‘What have they to laugh about? Surely they didn’t want to go to war?’

Italian captains and sergeants walked around in pairs, well-groomed in spotless uniforms. Other groups of tall blond men dressed in long beige gabardines and smart trilby hats looked around, cigarettes in hand, no hurry to go anywhere.

Carlo noticed a lot of ragged tramps and beggars, sitting in corners, beards and hair unkempt. A mother, dishevelled and barefoot, sat on a dirty step begging. As he looked closer, he noticed she held a baby wrapped in an grubby shawl and old newspapers to add some warmth.

Carlo felt his stomach lurch. ‘Oh, Mamma.’

It had been so hard to leave his mother yesterday. How will she manage without him? He never realised till now, how much he loved her. How much he relied on her. She had always put him first, always given him the best of everything. She always gave him his breakfast, his milky coffee and his pavesini biscuit; the one from the market stall. At the end of the month, on pay day, she always made a pot of ragu, thick tomato sugo with chunks of juicy meat that had cooked so slowly it melted in your mouth. He could almost smell it. His stomach cramped in hunger.

He thought of the many times she sat up at night waiting for him to come home. Marcello from the farmacia knew someone who worked in Cinema Sacchini. He sometimes gave Carlo free tickets. They were really tickets from the day before that he stamped with a ‘gratis' over the date, but it got them into the back row anyway. Carlo would go and get lost for an hour or two of dreams of glamorous lives, music and excitement.

When late at night he arrived home his mother was always waiting, watching for him from the balcony. She would have a warming plate of pasta aglio e olio ready for him, just so he would sleep well, dreaming of her instead of pretty girls.

His eyes filled with tears again.

‘Madonna mi aiuto! How will I manage without Mamma?’

Just then, a whiff of perfume caught his nostrils.

He turned round quickly and walked right into the embrace of a tall, elegant woman, fully draped in a luxurious, knee length fur coat.

Carlo took a step back, embarrassed, bumping into Egidio, almost knocking him over.

‘Mi scusi, signorina, signora?’ Carlo blushed.

She nodded gracefully; her deep ruby red painted lips parting slightly to show a row of small, gleaming teeth. She smoothed her hand down her chest to straighten the fur on her coat.

‘Niente, caro,’ her voice was deep and slow with a strange accent.

She smiled at him, and touching his face gently with her cool fingers, her red painted nails long and perfectly shaped, she tipped her head to the side and turned around and slowly strolled away.

Carlo looked at her, her coat swinging seductively, her long stockinged legs with a seam stretching straight up, her narrow ankles perched in dark polished shoes with the narrowest of high heels.

Egidio nudged him.

‘Are you in love? ‘ he laughed.

Carlo pulled himself together.

‘No…’ but he was hot under the collar, ‘No, but I bet she’s in love with me!’

Carlo’s thoughts of his mother went clean out of his head. Maybe this adventure would be fun after all.

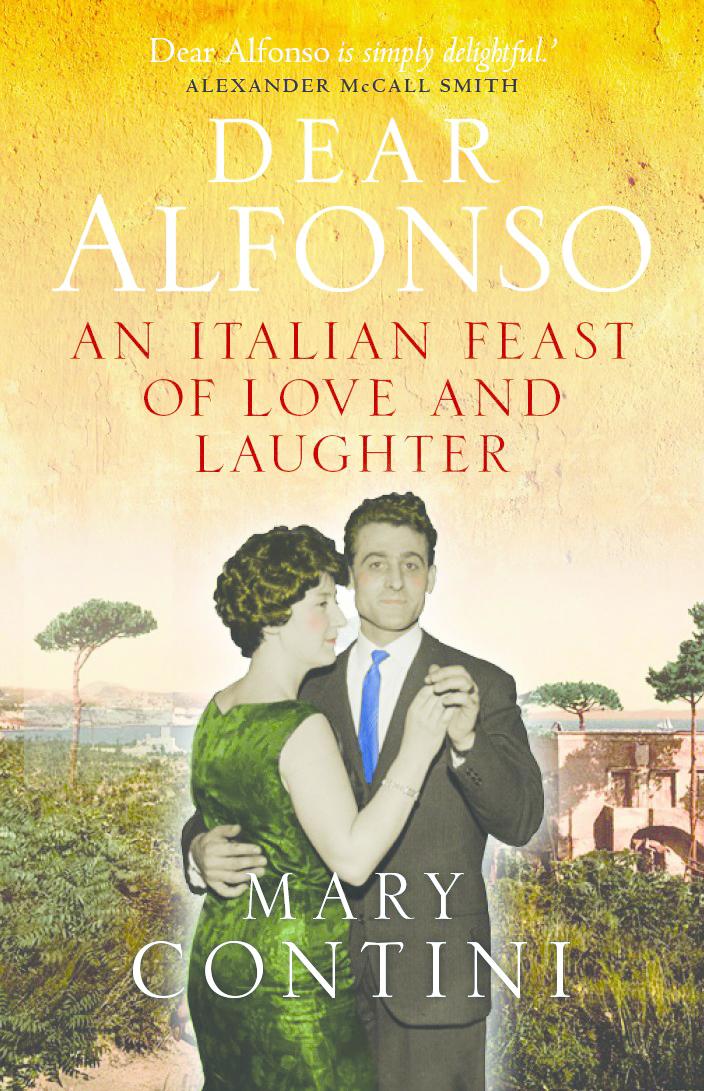

Extract from Mary Contini's Dear Alfonso

Why are you making commenting on The Herald only available to subscribers?

It should have been a safe space for informed debate, somewhere for readers to discuss issues around the biggest stories of the day, but all too often the below the line comments on most websites have become bogged down by off-topic discussions and abuse.

heraldscotland.com is tackling this problem by allowing only subscribers to comment.

We are doing this to improve the experience for our loyal readers and we believe it will reduce the ability of trolls and troublemakers, who occasionally find their way onto our site, to abuse our journalists and readers. We also hope it will help the comments section fulfil its promise as a part of Scotland's conversation with itself.

We are lucky at The Herald. We are read by an informed, educated readership who can add their knowledge and insights to our stories.

That is invaluable.

We are making the subscriber-only change to support our valued readers, who tell us they don't want the site cluttered up with irrelevant comments, untruths and abuse.

In the past, the journalist’s job was to collect and distribute information to the audience. Technology means that readers can shape a discussion. We look forward to hearing from you on heraldscotland.com

Comments & Moderation

Readers’ comments: You are personally liable for the content of any comments you upload to this website, so please act responsibly. We do not pre-moderate or monitor readers’ comments appearing on our websites, but we do post-moderate in response to complaints we receive or otherwise when a potential problem comes to our attention. You can make a complaint by using the ‘report this post’ link . We may then apply our discretion under the user terms to amend or delete comments.

Post moderation is undertaken full-time 9am-6pm on weekdays, and on a part-time basis outwith those hours.

Read the rules here