BEING a sickly child, I spent a lot of time in the company of doctors, so it was probably not surprising that I resolved to become one. The white coat and wise aura attracted me, but I think it was the stethoscope and big desk that swung it.

I also spent a lot of childhood hours in the company of books. Smog regularly blighted Glasgow in the late fifties. It exacerbated my asthma so I was often kept at home devouring Blyton, Verney, Brent-Dyer, my father's R.L. Stevenson, Compton Mackenzie, Rider Haggard and Wodehouse, soaking up history, humour and notions of foreign and lost worlds. At Queen's Park Secondary School my English teacher tried dissuading me from medicine. Teaching, he advised, was good for girls: 'home in time to cook your husband's tea.' After applying to study English and Medicine at Glasgow, Presbyterian guilt triumphed. English seemed self-indulgent while sickness needed cured.

I loved medicine, never dull, providing lifelong friendships cemented during long nights watching one another's backs while responsible for life and death. Terrifying. Finding hospital medicine offered no provision for part-time work and biological clock ticking, I headed for General Practice and spent 31years in a privileged occupation easing patients through illness, bereavements and births. Unhappily, GP Maternity Units have vanished. Ours closed for 're-decorating' never to re-open. I also mourn the disappearance of continuity of care. With GP shortages you're lucky to see any family doctor now, never mind one who's known you since childhood. Such knowledge definitely saved time (and money) by allowing swifter diagnosis and reduced referrals. Though sometimes we learned too much about our patients. (Beware any GP in a Ferrari…) I still miss patients, still get odd hugs in Tesco, but don't miss the soul-destroying collection of health data never utilised (as far as I could see) by Health Boards.

It was battling for patients that started me writing. In 1989, incensed at Maggie Thatcher's bonkers NHS plans, I wrote an exasperated letter to the Herald who published it as an article and engaged me for a regular column. Thereafter I had a parallel journalism career in the medical and lay press, venting spleen on the vagaries of patients, the state of the NHS, and the inability of politicians to grasp its mechanics. But becoming disillusioned by my failure to convince patients to change unhealthy lifestyles, at 52, I set off to a sabbatical Medical Anthropology Masters at Oxford. My report to the Scottish Office concluded the best way to improve mortality rates - and economic growth - is female education, hence the reason my debut novel Not The Life Imagined benefits Plan International's aim to cut the 130 million girls world-wide denied schooling.

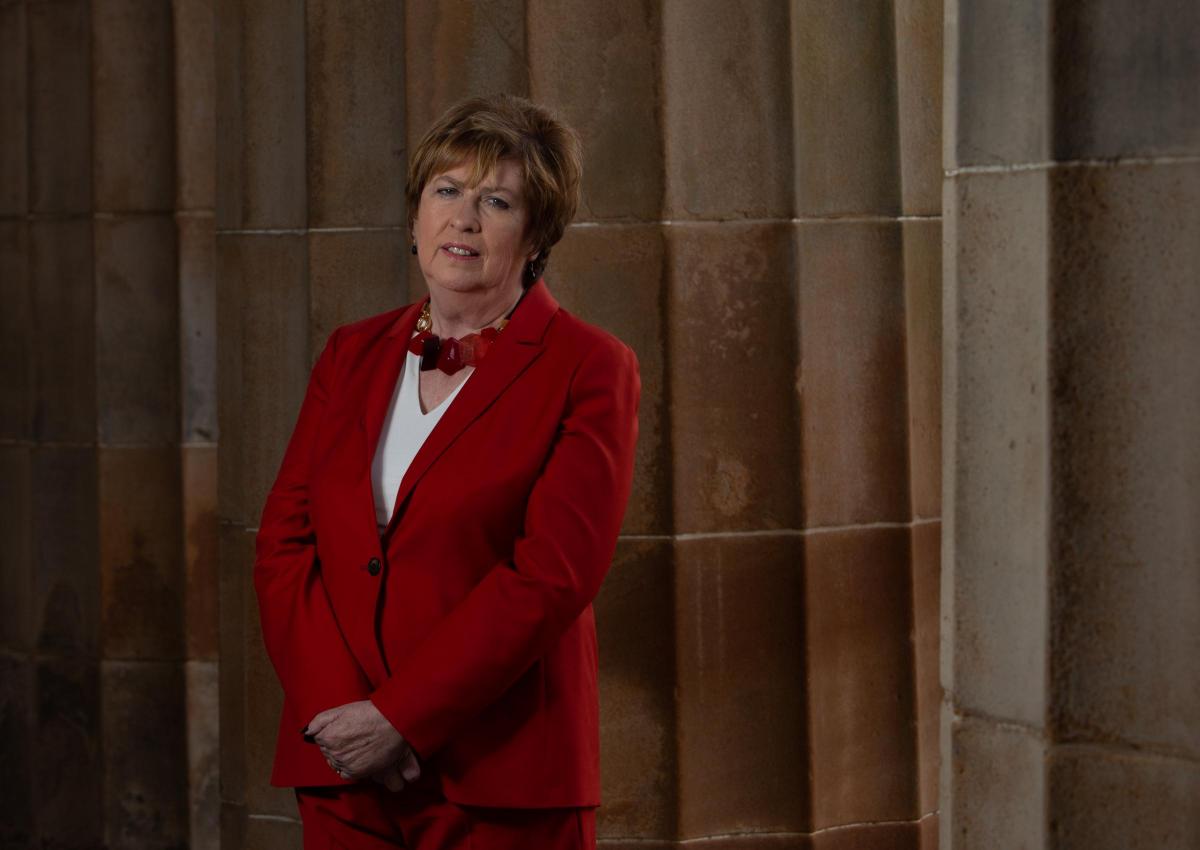

The crime-writing came after retiral. Not fancying slippers and reckoning you're a long time dead, I decided to write a novel about women doctors, absent in literature unless as pioneers or pathologists. University of Glasgow Creative writing classes were a revelation. My tale morphed from a historical depiction of life for female sixties Glasgow medical students into a darkly humorous romp with disastrous relationships and disappearing bodies nicknamed in class 'Sex and Scalpels.' Finally called Not The Life Imagined, it was runner-up in the SAW Constable Silver Stag Award 2018 and published by lovely non-profit Ringwood who've submitted it for a Saltire. It's been stressful coping with social media promotion (writing is much easier) but I'm thrilled to be chosen as a Spotlight Author at Bloody Scotland appearing alongside Prof Angela Gallop and her authoritative book on forensic science. At 69 it's nice to be up and coming… Book two on the way.

Not The Life Imagined is available from Ringwood, Amazon and Waterstones. Anne Pettigrew and Professor Gallop are at Bloody Scotland, Stirling, on September 22 at 11am. Visit bloodyscotland.com

Why are you making commenting on The Herald only available to subscribers?

It should have been a safe space for informed debate, somewhere for readers to discuss issues around the biggest stories of the day, but all too often the below the line comments on most websites have become bogged down by off-topic discussions and abuse.

heraldscotland.com is tackling this problem by allowing only subscribers to comment.

We are doing this to improve the experience for our loyal readers and we believe it will reduce the ability of trolls and troublemakers, who occasionally find their way onto our site, to abuse our journalists and readers. We also hope it will help the comments section fulfil its promise as a part of Scotland's conversation with itself.

We are lucky at The Herald. We are read by an informed, educated readership who can add their knowledge and insights to our stories.

That is invaluable.

We are making the subscriber-only change to support our valued readers, who tell us they don't want the site cluttered up with irrelevant comments, untruths and abuse.

In the past, the journalist’s job was to collect and distribute information to the audience. Technology means that readers can shape a discussion. We look forward to hearing from you on heraldscotland.com

Comments & Moderation

Readers’ comments: You are personally liable for the content of any comments you upload to this website, so please act responsibly. We do not pre-moderate or monitor readers’ comments appearing on our websites, but we do post-moderate in response to complaints we receive or otherwise when a potential problem comes to our attention. You can make a complaint by using the ‘report this post’ link . We may then apply our discretion under the user terms to amend or delete comments.

Post moderation is undertaken full-time 9am-6pm on weekdays, and on a part-time basis outwith those hours.

Read the rules here