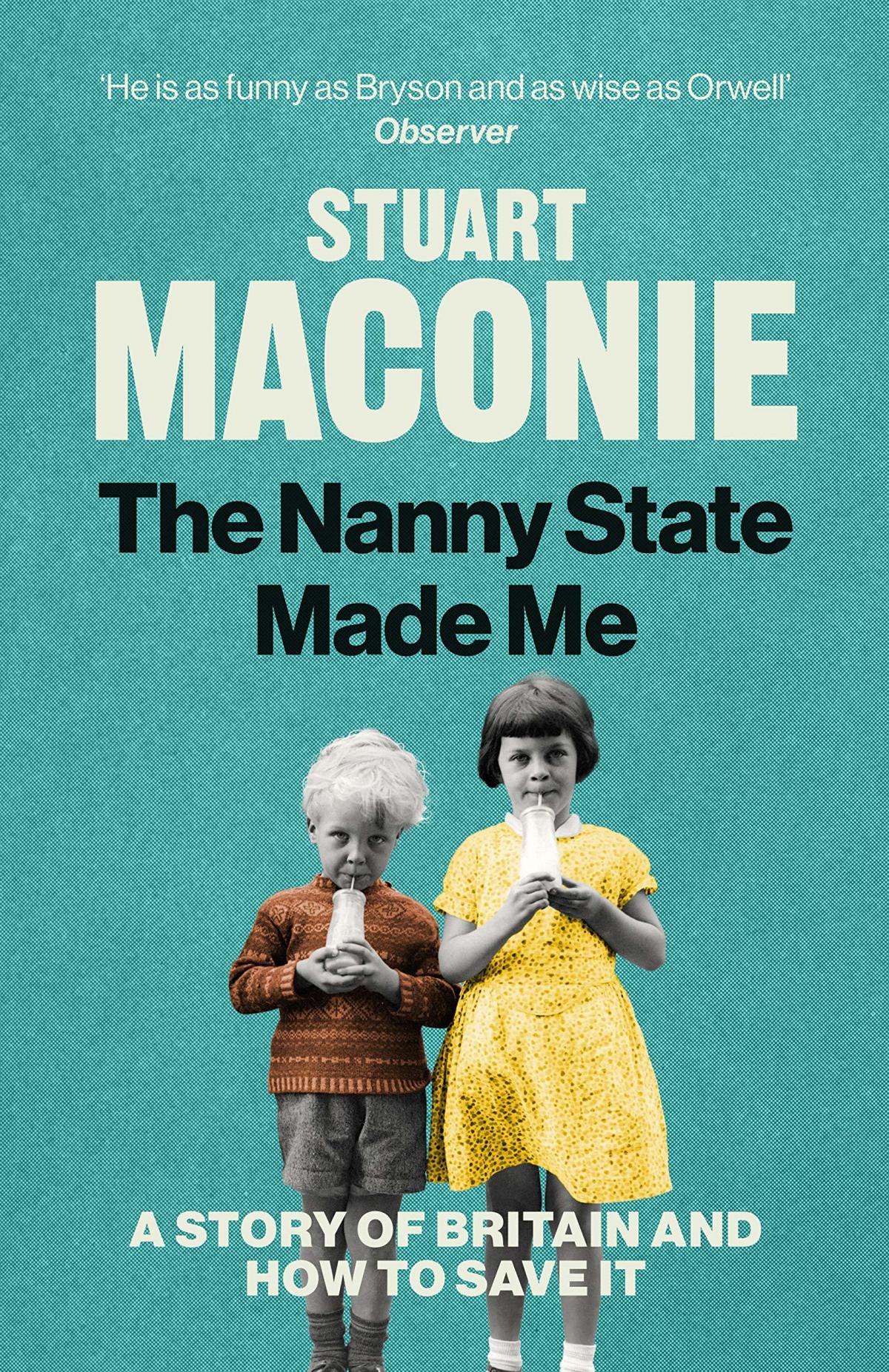

The Nanny State Made Me

Stuart Maconie

Ebury Press £20

IN the way that all football deflections are wicked, all suburbs are leafy and all security is tight, it is mandatory that all nostalgia must be misty-eyed.

Stuart Maconie’s reminiscence of a life led under the capacious, comfortable and beneficial swing of nanny state’s skirts falls snugly into that category. It produces the odd tear occasioned by sentimental nostalgia and the more than regular blurring of vision occasioned by justified anger.

However, the misty-eyed can struggle to retain focus. There is much to admire in Maconie’s examination of the welfare state and how it is being systemically destroyed but there are also large areas that escape his examination to the ultimate detriment of his purpose.

His premise is simple: he seeks to praise what society, under the auspices of government funding, has done for him and others. He concentrates, in his lively and gently humorous style, on matters of birth, education, council housing, health, welfare payments and travel. He challenges, robustly and successfully, the lazy belief that the 1970s – the time of the nanny state at her most powerful – was somehow a living hell.

Maconie’s credo could be expressed in a single paragraph and, indeed, has been by the wonderful Grace Maxwell, who among other things is the wife of the equally divine Edwyn Collins. In response to nonsense spouted about the “wretched 1970s”, she tweeted: “In 1975, I sailed off to Glasgow University from my council house, in a steelworkers’ town, maximum grant, fees paid, part-time job in Woolworths, no burden on my parents, with a spring in my step, in glorious technicolour. Utterly wretched my a***.” This is an experience shared by a generation. It surely would prompt disbelief and envy among the young strivers of the 2020s.

As Maconie points out, the criticism of the nanny state is led by those who have had nannies. Their influence, though, has been strong and their arguments astonishingly persuasive to those who should not be banishing the nanny state but clutching her close to their bosom. There is a moment when Maconie is interviewing Andy Burnham, now mayor of Manchester, on the chaos caused by de-regulation of the buses. Almost as an aside, he mentions that Leigh, Burnham’s former seat, has been lost to the Tories. Whit? A quick recourse to the internet reveals that this is the first time the Conservatives have won the seat. Ever.

This deserves further examination. It seem to fall outside Maconie’s remit but is surely central to his subject matter. How did Leigh and other political seismic shifts occur?

Maconie, at 58, is a child of the state much in the same way as myself, at six years older. Our experiences of life under national bureaucracy and benevolence are similar, though blessedly I have never “signed on” though I have used the National Health Service more often than the Lancastrian writer. I also cannot find identification with Maconie’s assertion that the buses once ran on time. There was once a stop on St George’s Road in Glasgow – notorious for the non-arrival of buses – that became a favoured gathering place for vultures in the 1970s. I also fail to remember the outpouring of joy at England’s victory in the 1966 World Cup. Caledonian aficionados of this obsession with Wembley 66 will be delighted to note that it is mentioned on page 2.

This jab at the fitba’ is, of course, merely joshing but it disguises a genuine issue. Maconie has shared the benefits of the nanny state with so many Scots of a similar age but there is a stark difference that is not explored. The death sentence on nanny state – leading to a long, painful but inexorable demise – was signalled by the accession of Margaret Thatcher to the prime ministerial office in 1979. One can accuse her of so much but never of overt pretence about her intentions. Her contemporary successors are similarly stark in their ambitions, though there are those who can be gulled by the side of a bus.

The point is that taking a baseball bat to public spending has been a national sport for the Tories for some considerable time. Further, it has won favour at the ballot box.

I will be 65 this year. This was once the age when a national pension was bestowed, though that has been delayed in one of the more minor crimes of the reactionaries who know the price of everything but the value of nothing. But here’s the thing. As 65 approaches with all the speed and innate threat of a racing motorcyclist on, well, speed, I can reflect that my country has never endorsed the ethos of no society, austerity, isolationism in Europe or an end to manufacturing. I was three weeks old the last time Scotland voted Tory.

Now Maconie’s travels through Britain included trips to Glasgow and the Shetlands and his findings have an undoubted resonance throughout these islands. The effects of unbridled attacks on spending on communities or suffering individuals are uniform. There may, too, be an accusation that this reviewer is indulging in churlish chauvinism.

But it leaves a central question. How has the electoral power been found to effect changes that have profound damaging effects on those who vote for them? How is this been gained in England but not in Scotland?

The game is rigged as Maconie points out with judicious use of statistics and entertaining and informative chats with mates such as Caitlin Moran, Richard Hawley, Simon Armitage, Hunter Davies and others. The subsidies to those who fall by the wayside are cut while the subsidies offered to private schools are wilfully ignored. It is obscene.

Yet a bunch of posh boys and girls have persuaded the masses in large tracts of what was one industrial and working-class England – which are heavily populated now by the unemployed and the disillusioned – to back more restrictions on state aid to the individual. It is the sort of cunning trick that prompts demands to put turkeys on the electoral register in time for Christmas.

Maconie’s articulation of the problems is heartfelt, sentimental but also bolstered by fact. He resolutely matches his polemic with recourse to statistics. It is a useful, but not essential, addition to a canon of investigations into the state of Britain that includes a cluster of classics such as George Orwell’s Road to Wigan Pier, Richard Hoggart’s The Uses of Literacy and the more recent but utterly compelling Dreams of Leaving and Remaining by James Meek.

Maconie is not at this rarefied level, particularly given the omission of an investigation into not only how Britain arrived at this state of affairs but remains there. This is so glaring a fault that it makes one misty-eyed.

He has, though, given a state of the nation address that is oddly made the more powerful for being spoken in his fluid, often amiable style. There is much to applaud in what is a slim volume but one that ranges across the experiences of a life regularly lifted by the unseen hand of state.

There are many lessons that he gently offers, none more affecting that once there was a large blanket that could be found in times when chill reality intruded, whether as a child, as an unemployed worker or as someone who has simply lost their way. This blanket was applied with an inefficiency and incontinence that certainly could raise hackles in the press and in the minds of the reactionary but it was there. And one was as glad to have found it as one was horrified by needing it.

The reality now irrefutable. That blanket is now threadbare, disintegrating before the eyes, misty or otherwise.

Why are you making commenting on The Herald only available to subscribers?

It should have been a safe space for informed debate, somewhere for readers to discuss issues around the biggest stories of the day, but all too often the below the line comments on most websites have become bogged down by off-topic discussions and abuse.

heraldscotland.com is tackling this problem by allowing only subscribers to comment.

We are doing this to improve the experience for our loyal readers and we believe it will reduce the ability of trolls and troublemakers, who occasionally find their way onto our site, to abuse our journalists and readers. We also hope it will help the comments section fulfil its promise as a part of Scotland's conversation with itself.

We are lucky at The Herald. We are read by an informed, educated readership who can add their knowledge and insights to our stories.

That is invaluable.

We are making the subscriber-only change to support our valued readers, who tell us they don't want the site cluttered up with irrelevant comments, untruths and abuse.

In the past, the journalist’s job was to collect and distribute information to the audience. Technology means that readers can shape a discussion. We look forward to hearing from you on heraldscotland.com

Comments & Moderation

Readers’ comments: You are personally liable for the content of any comments you upload to this website, so please act responsibly. We do not pre-moderate or monitor readers’ comments appearing on our websites, but we do post-moderate in response to complaints we receive or otherwise when a potential problem comes to our attention. You can make a complaint by using the ‘report this post’ link . We may then apply our discretion under the user terms to amend or delete comments.

Post moderation is undertaken full-time 9am-6pm on weekdays, and on a part-time basis outwith those hours.

Read the rules here