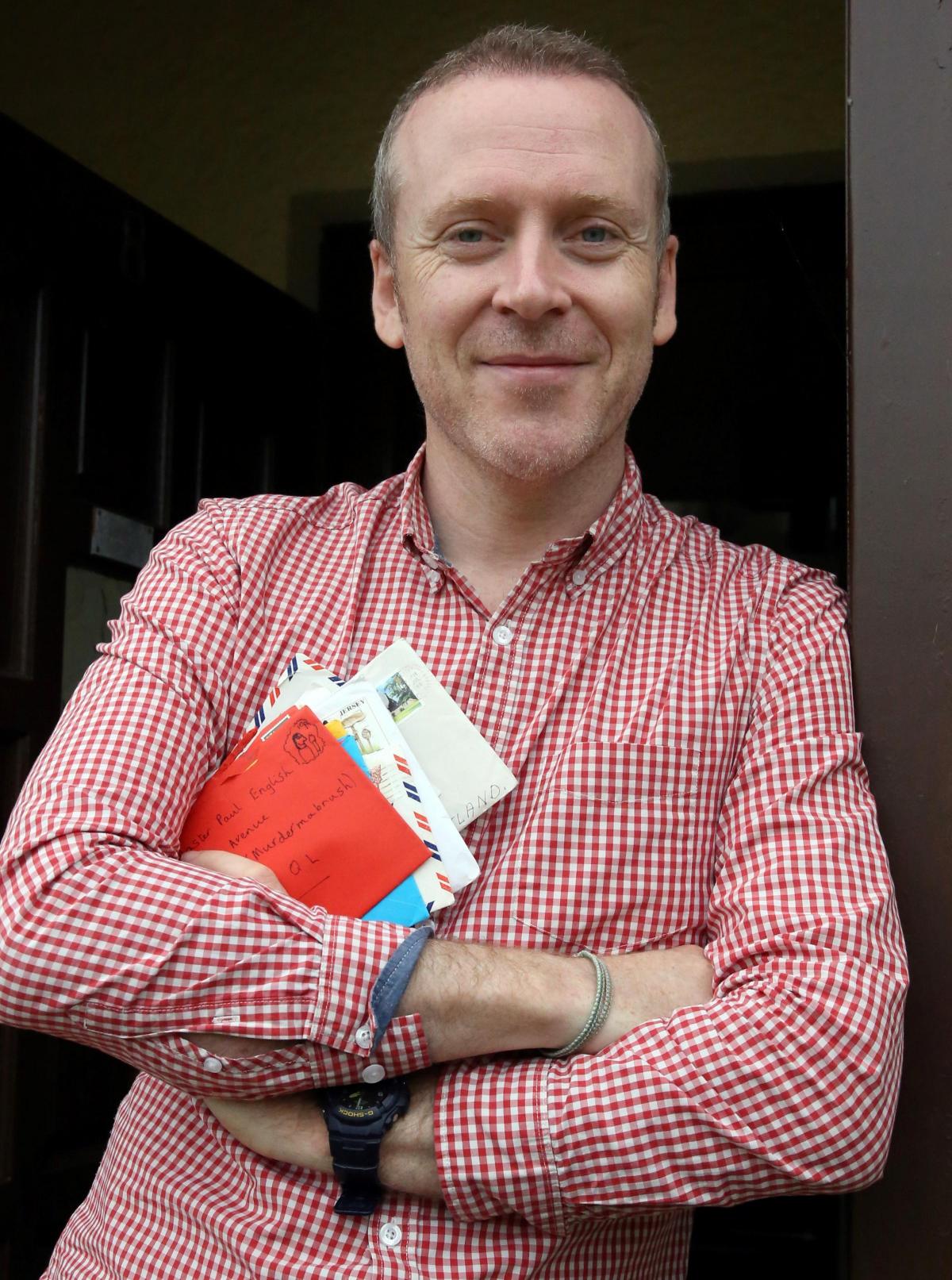

By Paul English

Pictures by Mark Gibson

HIS name is all but forgotten, yet among the shadows in back lanes of a row of shops on Glasgow’s southside, the imprint of his legacy remains, scorched in brick.

Burnt onto the walls of an old Victorian bakery are the marks left by the vision of an industrial revolutionary whose determination to empower, liberate and improve the lives of his workforce set him apart from the industry captains of Glasgow’s grimy workhouses in the mid 1800s.

Next weekend, a unique festival will remember the life of Neale Thomson, remembering the cotton factory heir as one of Glasgow’s greatest philanthropists, honouring his egalitarian vision with a jamboree pairing bread, music and politics in a celebration of local history, social reform and workers’ rights.

Rachel Smillie first came up with the idea of a festival inspired by Thomson when she opened The Glad Cafe in Shawlands on Glasgow’s southside in 2012, and began researching the history of the surrounding buildings.

Like the best breads, her idea has been slow to rise.

She said: “I discovered that the buildings had been part of a bakery set up in the 1840s by a guy called Neale Thomson whose father and grandfather had run the Adelphi Cotton Works in Gorbals and made themselves a fortune in the 1800s.

“He wasn’t destined to take over the factory because he was the third son, and went to university. But his brothers died and he found himself in charge.”

Thomson, who’d studied at the University of Glasgow, established the bakery as part of a series of utopian ventures aimed at improving the lot of his workforce in the cotton factory.

Smillie said: “He’d become aware of the modern ideas of the time around social reform, and was concerned that his workers weren’t able to buy a decent loaf of bread, because bread was poor quality and expensive.

“So he decided to start up a bakery specifically to provide bread that was good quality and cheap for his workers.”

The bakery, in what was then known as the village of Crossmyloof, now Shawlands, earned a reputation for the quality of its “Crossmyloof loaf”, and ten Crossmyloof Bread shops were established around Glasgow.

Yet Thomson’s principles went beyond the loaf and against the grain of the times when conditions for industrial workers were typically appalling.

“He was also concerned about the working conditions for bakers,” said Smillie. “In those days a journeyman baker was required to work for 20 hours a day with no days off and generally slept on the premises. So they couldn’t marry or have children.”

Today, Shawlands is one of the city’s most popular areas, yet the touchstones of Thomson’s influence on the area are appreciated by few who live and play on the area’s streets.

He gifted land from his family estate for the building of a church (on the site now occupied by St Helen’s RC church near to The Shed nightclub) and built a school (which now houses a coffee shop and Indian restaurant on nearby Skirving Street).

Architect Alexander “Greek” Thompson was commissioned to build a row of houses for the workforce on what became Baker Street, which were demolished in the 1980s, and land from his family’s estate was sold to the city for less than its value.

Today the land is known as Queen’s Park, one of the Dear Green Place’s most popular municipal open spaces. Thomson’s grand family home, Camphill House, is now divided into flats in the park.

Shawlands resident Anna Nisbet, an architect who previously helped design a Doors Open Day programme on the site of the Crossmyloof Bakery, is co-organiser of the festival.

She helped design a Neale Thomson heritage trail which will be launched next week, enabling visitors to take part in self-guided tours of the remnants of Thomson’s influence.

Dozens of children from nearby primary schools have also been signed up to take part in ongoing projects in which they trace the industrialist’s footsteps.

Nesbit spent hours researching Thomson’s history in the city’s Mitchell Library - including articles from The Herald - and discovered his work drew dissent from some quarters.

He was accused of making sub-standard bread in smear campaigns from rivals, and of undermining the prevailing employment practices meted out by other bakers around the country.

She said: “There was information in parliamentary papers that showed there’d been a debate in parliament 15 years after the bakery had opened. London workers were trying to get the same conditions that his workers had. There’s a full letter written by his bakery manager, Mr Dalgetty, explaining that they had changed the working hours, that the bakery was still profitable and had healthy staff, and assuring the Bakers’ Association in London they could make these changes.

“We found that he encouraged all his workers to open bank accounts. He asked to see their bank books by the end of the year, and they were all very hesitant to hand them over. But when they did, he matched whatever they’d saved. He also brought in a 12 hour working day and a day off every second Sunday.”

Smillie added: “People would queue up for his bread around the city, and that that led to bakery wars. If his manager ever went into the city in the evening, he had to have an armed escort with him, otherwise people would jump him.”

Both women point to the obvious influence on Thomson of Robert Owen and David Dale’s earlier celebrated New Lanark industrial project, which saw mill-workers well-treated, healthy and content in the 1800s.

Nisbet said: “He had a real impact on what was the old village of Crossmyloof. These buildings, on a large site, remain in the city, and it feels like a small New Lanark which nobody knows about.

“He really was ahead of his time in thinking about workers’ rights and conditions.”

Smillie recently discovered Thomson’s grave in Cathcart Old Parish Church, where he is buried with his wife Helen and several of their children, who carried on the business after his death in 1857. The bakery survived until 1880.

“There are some lovely things said about him and his wife on the tombstone,” she Smillie. “They seemed to be two genuinely decent, very philanthropic people who supported each other in their various endeavours.”

On first discovering the story of the bakery, Smillie commissioned a new loaf to be sold at The Glad Cafe, marking Thomson’s impact and ensuring his legacy can not only be seen, but tasted.

She said: “I loved the story of Neale Thomposn and thought of we were on the site of the old bakery, we thought it would be nice to sell something that represented what was going on here. So we decided to sell our own version of it here, and called it the Crossmyloaf.”

The festival, funded by the National Lottery’s Heritage Fund, will include speakers and demonstrations from independent bakers and farmers from around Scotland.

And in the mix, there’s a nod to those who abide by Thomson’s humanitarian ethics today.

“We’ve asked a lot of different bakers to come including Freedom Bakery who work with prisoners, and High Rise Bakers who work with asylum seekers and other marginalised people near the site of the Adelphi cotton factory,” said Smillie.

Guided walks of Thomson heritage trail, including a visit to see the ghost-prints left by the ovens over 100 years ago in what is now a printing firm, will be held every hour, and the event will rounded off with a gig at the Glad Cafe, featuring indie acts including Kathryn Joseph with members of Modern Studies and Trembling Bells.

“We want people to know about Neale Thompson and the amazing work he did, and to engage people with the importance of good bread,” said Smillie.

“Poorly-made bread has an effect on people’s bodies and we want there to be a greater commitment to producing good-quality bread, supporting people who are trying to make good things for the Scottish diet, that isn’t too expensive and which provides them with a living which is manageable. That’s really what Neale Thomson was trying to do.”

“It feels important to celebrate his legacy right now, because there is such a focus on workers’ rights and trying to make society more equal at that time,” said Nisbet.

“The festival is historically-based, but there’s a political undertone to it. It feels that we’re going backwards in society just now, where we have zero-hours contracts and real problems with inequality.

“It’s really important to show that in 1850 they were trying to deal with this issue, and yet here we are again with the same kind of problems, going in the wrong direction.”

Crossmyloof Bread Festival, The Glad Cafe, Glasgow, 21 April, from 11am.

Why are you making commenting on The Herald only available to subscribers?

It should have been a safe space for informed debate, somewhere for readers to discuss issues around the biggest stories of the day, but all too often the below the line comments on most websites have become bogged down by off-topic discussions and abuse.

heraldscotland.com is tackling this problem by allowing only subscribers to comment.

We are doing this to improve the experience for our loyal readers and we believe it will reduce the ability of trolls and troublemakers, who occasionally find their way onto our site, to abuse our journalists and readers. We also hope it will help the comments section fulfil its promise as a part of Scotland's conversation with itself.

We are lucky at The Herald. We are read by an informed, educated readership who can add their knowledge and insights to our stories.

That is invaluable.

We are making the subscriber-only change to support our valued readers, who tell us they don't want the site cluttered up with irrelevant comments, untruths and abuse.

In the past, the journalist’s job was to collect and distribute information to the audience. Technology means that readers can shape a discussion. We look forward to hearing from you on heraldscotland.com

Comments & Moderation

Readers’ comments: You are personally liable for the content of any comments you upload to this website, so please act responsibly. We do not pre-moderate or monitor readers’ comments appearing on our websites, but we do post-moderate in response to complaints we receive or otherwise when a potential problem comes to our attention. You can make a complaint by using the ‘report this post’ link . We may then apply our discretion under the user terms to amend or delete comments.

Post moderation is undertaken full-time 9am-6pm on weekdays, and on a part-time basis outwith those hours.

Read the rules here