St Kilda

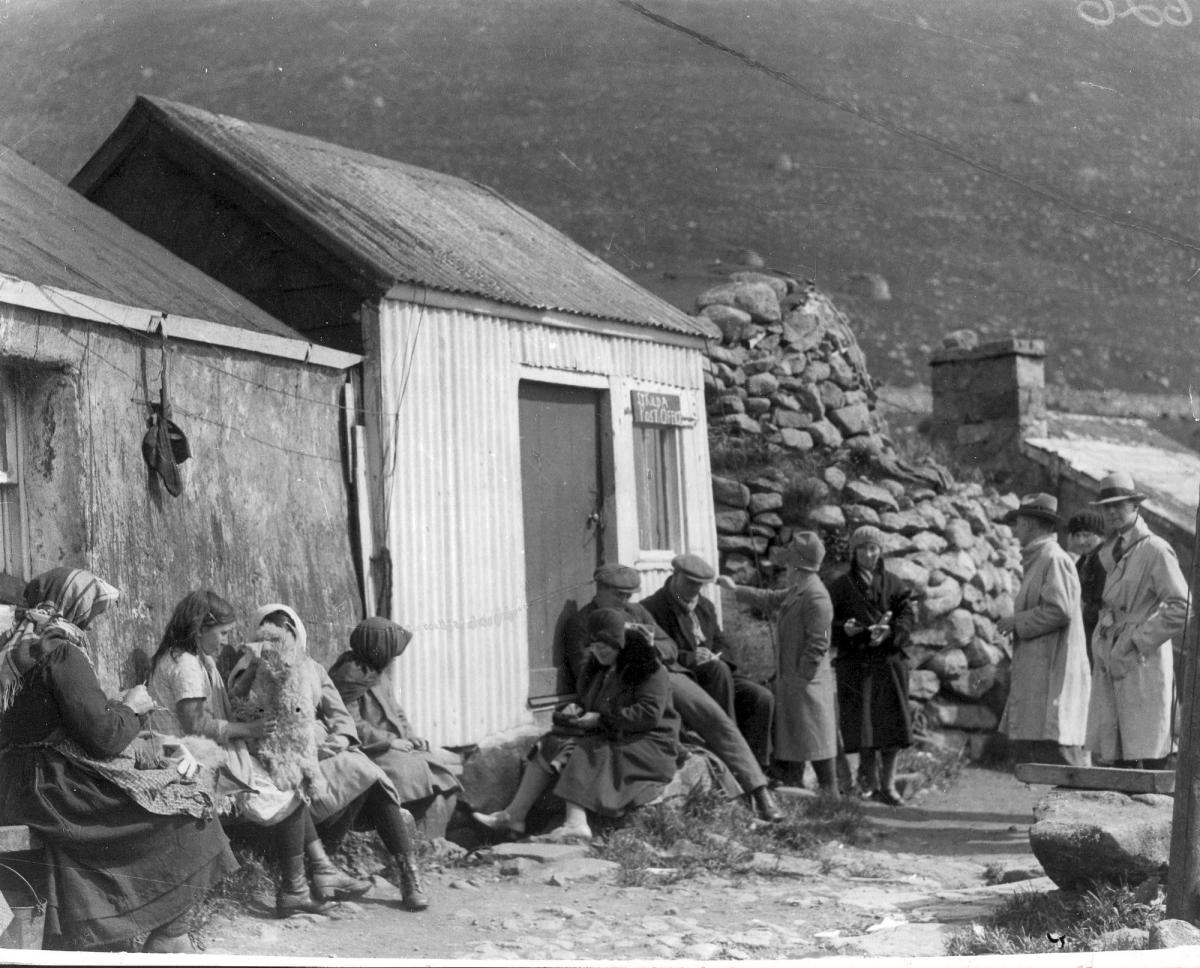

A community existed on St Kilda for at least 4,000 years, sustained largely by dense colonies of gannets, fulmars and puffins for food, feathers and oil.

Yet, by the late 19th and early 20th centuries, crippling shortages, a succession of crop failures, deadly diseases brought in by tourism, coupled with emigration and the upheaval of the First World War, left the St Kilda economy irreparably broken.

With their way of life no longer viable, the remaining 36 residents chose to be evacuated from the island on August 29, 1930.

Today, St Kilda is home to almost one million seabirds, including the UK's largest colony of Atlantic puffins, as well as its own unique sub-species of wren and mice, the latter double the size of a British field mouse.

The "Viking Shipyard" at Rubh an Dunain in Skye

The isolated peninsula of Rubh an Dunain on Skye's southwest coast has several archaeological sites dating from the Neolithic period onwards.

Among them is a man-made canal linking an inland loch to the sea – converting it into a dry dock and "shipyard". In 2009, archaeologists discovered boat timbers dating to the 12th century, a stone-built quay and a system used to maintain a constant water level in the loch.

READ MORE: How the secrets of Skara Brae were revealed

The shallow waterway would have allowed for boats, such as birlinns, to exit at high tide. It is believed this was an important site for maritime activity – perhaps as a factory for producing or repairing vessels – spanning the Viking and later periods of Scottish clan rule.

In 2017, Historic Environment Scotland (HES) officially designated it as an historic monument.

Bothwellhaugh, Lanarkshire

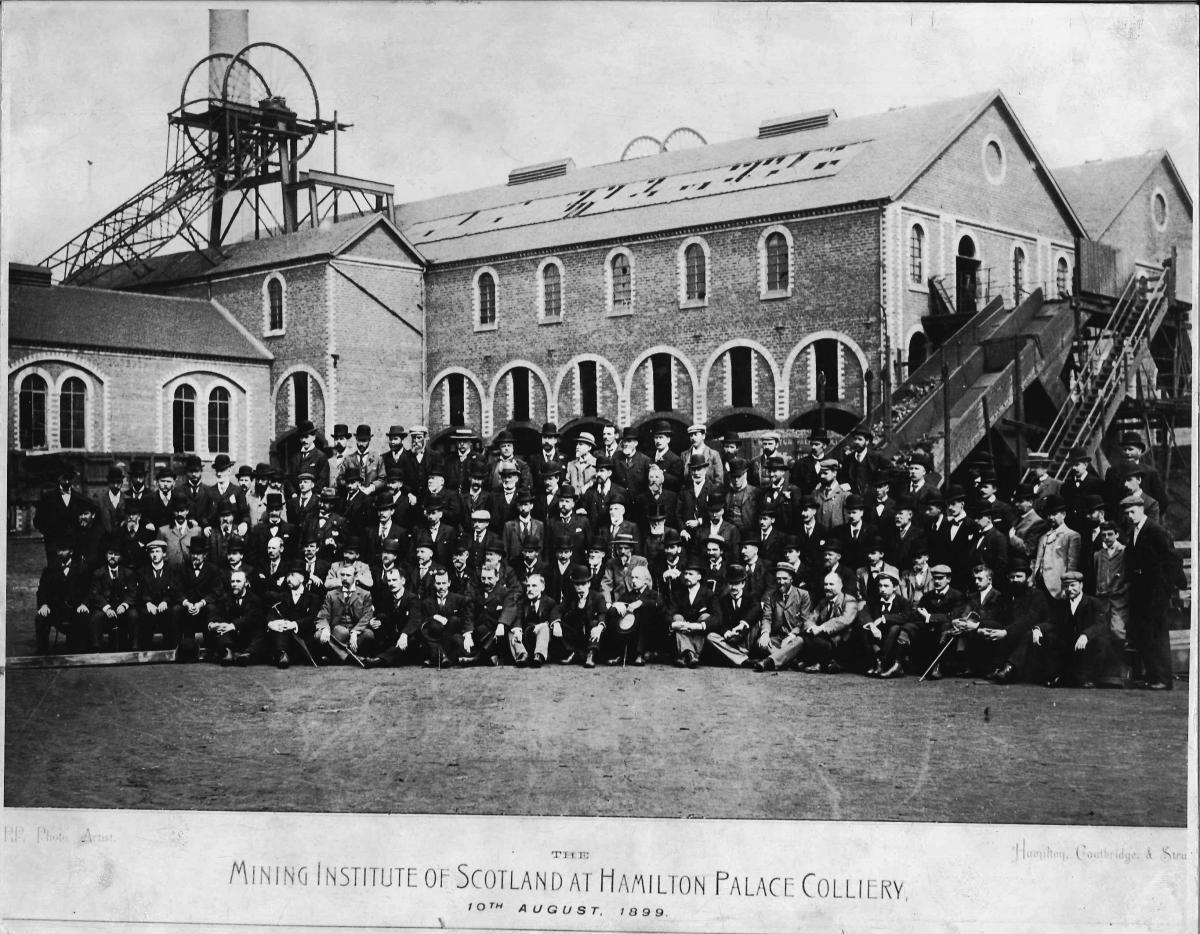

The former mining village of Bothwellhaugh stood on the banks of the Clyde, built in 1884 for workers employed by the Bent Colliery Company and their families. It was known as "the Pailis", a fond colloquialism for the Hamilton Palace Colliery.

By 1911, the colliery's initial crew of 14 miners had swelled to a thriving community of 2,500 people. There was a church, two schools, a miner's welfare club and 450 homes.

The coal produced here was high quality and sought after for industrial use, particularly as fuel for steam trains, with much of it exported to Argentinian railway companies. The Flying Scot's record run to London is reputed to have used Pailis coal.

After the pit closed in 1959 – the last of the tenement rows were demolished in 1965 – those who worked and lived here moved on. While some were rehoused nearby in Bellshill, Motherwell and Hamilton, others emigrated to Australia, Canada and the United States.

READ MORE: How the secrets of Skara Brae were revealed

Strathclyde Country Park was officially opened in 1978. The Clyde was re-routed and the Calder Pond incorporated into the new Strathclyde Loch. The pit's bing was used build the M74 motorway on the other side of the river.

The only remaining building is Raith Cottage where it is hoped a heritage centre can be opened to share the history of the site.

Rosal, Sutherland

The outlines of more than 70 ruined buildings sit on a hillside overlooking Ben Loyal and the wild, remote lands of Sutherland. This was once Rosal, a small township in Strathnaver that, until 1814, housed a close-knit Highland community.

Elizabeth, Countess of Sutherland, who owned the land, sought to maximise financial opportunities and with meat in high demand for the growing population in the south, sheep farming promised far greater profits than the tenants could offer in rent.

The residents of Rosal were forced to leave, their homes and livelihoods swept away by the clearances which transformed the cultural landscape across large swathes of the Highlands.

The estate factor, Patrick Sellar, undertook his work with a merciless efficiency: he was tried for culpable homicide following the death of an elderly woman at the nearby Badinloskin.

Archaeologist Horace Fairhurst carried out an excavation in 1962, recording 70 structures at Rosal, including longhouses, barns, outhouses, stackyards and corn-drying kilns, as well as the rigs and furrows where crops were grown.

Grahamston, Glasgow

The village of Grahamston first appeared on maps of Glasgow around 1680, growing over the next 200 years from a row of thatched cottages into a commercial and industrial hub.

At its peak, there was close to 2,000 people and almost 300 businesses, said to include well-known names such as philanthropist William Quarrier.

Before Glasgow Central Station was built, trains would arrive at Bridge Street on the south of the River Clyde. As the industrial revolution gathered pace during the 1870s, plans for a new rail terminus were proposed.

With the fate of Grahamston sealed, its residents – who lived between Union Street and Hope Street – were decanted and the buildings demolished. Glasgow Central opened in 1879, it's eight platforms and eight lines running through what had once been the heart of Grahamston.

READ MORE: How the secrets of Skara Brae were revealed

The western side of the village, including St Columba's Church, remained intact until the early 1900s, when the remainder was demolished to make way for a station extension.

Today, only two buildings remain: Duncan's Temperance Hotel, now the Rennie Mackintosh Hotel, in Union Street, and the Grant Arms at Argyle Street.

Why are you making commenting on The Herald only available to subscribers?

It should have been a safe space for informed debate, somewhere for readers to discuss issues around the biggest stories of the day, but all too often the below the line comments on most websites have become bogged down by off-topic discussions and abuse.

heraldscotland.com is tackling this problem by allowing only subscribers to comment.

We are doing this to improve the experience for our loyal readers and we believe it will reduce the ability of trolls and troublemakers, who occasionally find their way onto our site, to abuse our journalists and readers. We also hope it will help the comments section fulfil its promise as a part of Scotland's conversation with itself.

We are lucky at The Herald. We are read by an informed, educated readership who can add their knowledge and insights to our stories.

That is invaluable.

We are making the subscriber-only change to support our valued readers, who tell us they don't want the site cluttered up with irrelevant comments, untruths and abuse.

In the past, the journalist’s job was to collect and distribute information to the audience. Technology means that readers can shape a discussion. We look forward to hearing from you on heraldscotland.com

Comments & Moderation

Readers’ comments: You are personally liable for the content of any comments you upload to this website, so please act responsibly. We do not pre-moderate or monitor readers’ comments appearing on our websites, but we do post-moderate in response to complaints we receive or otherwise when a potential problem comes to our attention. You can make a complaint by using the ‘report this post’ link . We may then apply our discretion under the user terms to amend or delete comments.

Post moderation is undertaken full-time 9am-6pm on weekdays, and on a part-time basis outwith those hours.

Read the rules here