SOME elements of landscape are reminders of endurance. The Northern Gannet colony on the Bass Rock – rated by Chris Packham as his number one natural spectacle, and by David Attenborough as one of the great wonders of the natural world – is one such.

For centuries it has seen a blizzard of birds come back again and again to breed, nest, and deposit their guano on its rugged cliffs. We know that even back in 1521, the nesting there was already a famous natural phenomenon, mentioned in John Major’s History of England and Scotland.

This year’s birds started arriving around a month ago. Even as lockdown has started to leave us humans increasingly confined to our homes, more and more of the 150,000 who come each year have been descending on this plug of volcanic rock.

Were we free to travel, this is exactly the time of year we might begin to think about taking a boat trip, from the harbour in North Berwick out to the island, to see the birds in full operatic glory.

The fact that we’re stuck inside doesn’t mean we can’t appreciate this great island party in the sea. There are other ways to engage with it, for fortunately, The Bass Rock, has been written about through the ages, depicted in artworks and captured in stunning documentary footage.

From Robert Louis Stevenson’s Catriona to James Robertson’s The Fanatic, it has inspired countless writers and artists.

What we know of the Bass Rock can even put our own current isolation in perspective. In this time of social distancing, we think we know what being cut off from life is – the Bass Rock is a reminder of a more extreme isolation.

St Baldred is believed to have been one of its first inhabitants back in 600AD, a lone hermit living in a tiny, humble cell.

In 1671, it became Scotland’s Alcatraz when it was commandeered by Oliver Cromwell as “property of the crown” during his invasion of Scotland, and put to use holding Covenanters Around 40 political and religious prisoners died in the dungeons.

We can also think of the lonely keepers who worked the David Stevenson lighthouse there. Our homes might feel like prisons now, but they are nothing like the prison this hunk of volcanic rock was.

Yet, for all the dark tales that surround it, the rock, with its clouds of gannets, is a place we might want to travel in our imagination right now. It’s spring. The gannets will soon be nesting. Eggs will be hatching.

A wild, extravagant, excessive rebirth will take place. The colony on the rock can also often seem like a positive story in our times of biodiversity loss – for year on year, Scotland’s gannet population grows. It’s not a tale of disappearance, but of constant rejuvenation.

What to read (classic)

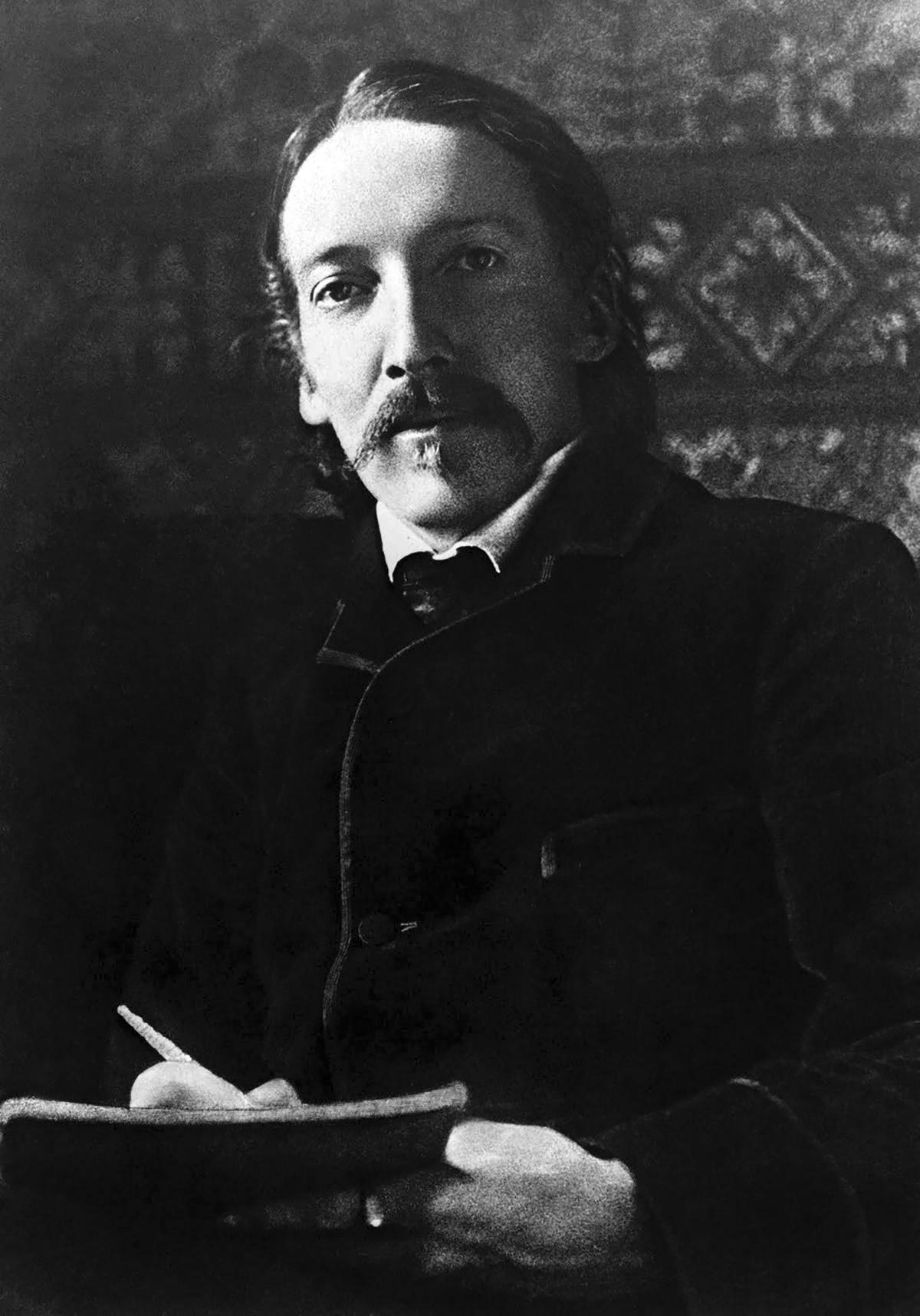

Robert Louis Stevenson had a thing about the Bass Rock. It’s there in his The Tale of Tod Lapraik, and, most significantly, in his sequel to Kidnapped, Catriona. His hero, David Balfour, is once again kidnapped and taken out there by boat.

“It is just the one crag of rock,” Balfour observes as he nears the rock, “as everybody knows, but great enough to carve a city from... With the growing of the dawn I could see it clearer and clearer; the straight crags painted with sea-birds’ droppings like a morning frost, the sloping top of it green with grass, the clan of white geese that cried about the sides, and the black, broken buildings of the prison sitting close on the sea’s edge. At the sight the truth came in upon me in a clap. ‘It’s there you’re taking me!’ I cried.”

What to read (contemporary )

The dark hunk of rock is a constant in the backdrop of Evie Wyld’s recently published gothic novel titled simply The Bass Rock. The book is a menacing interweaving tale of male violence against women, spanning centuries, populated by dead bodies and ghosts, in which one female character asks, “What if all the women that have been killed by men through history were visible to us, all at once?”

Another is troubled by the rock she looks out on. “She did not much like the rock,” Wyld writes. “Fidra and Craigleith she saw as charming additions, punctuation in the grey North Sea, but something about the Bass Rock was so misshapen, like the head of a dreadfully handicapped child.

“She often found herself drifting if she stared at it for too long, unable to look away, like the captivation she felt sometimes looking at her own face in the mirror, as if to look closely would be to understand it.”

Throughout it feels as if the Bass Rock, ever lurking, ever linking, must symbolise something, though it’s hard to know exactly what. Is it a metaphor for the enduring presence of male violence, of stubborn toxic masculinity? Or simply a forbidding presence.

Art to check out

Duncan Macmillan claimed to have discovered the earliest image of the Bass Rock in the form of a 16th century engraving by the Dutch master Pieter Bruegel the Elder. The Fall of Icarus depicts two figures flying close to the sun, not far from a rugged rock formation around which birds circle.

There are many more recent images though – including JMW Turner’s wildly atmospheric sketches and paintings.

What to get the kids into

The Scottish Seabird centre, seabird.org, has a page of home-learning activities to inspire kids throughout lockdown, including a link to a gem of a whiteboard animation on The Life Of A Northern Gannet.

What to watch

There have been many documentaries about the Bass Rock, though few are available to stream right now. Among them is Britain’s Secret Seas, which gives us a glimpse not only of the birds on the rock above, but the dazzling spectacle of them diving into the water, hitting its surface at around 40mph and plunging as deep as 20m – all from the point of view of diver and presenter Paul Rose.

What to listen to

Anything to do with birds. Dive and soar on an air current of dizzying sounds. Eleanor McEvoy’s The Seabird, Great British Power’s The Great Skua, Sia’s Bird Set Free, Nelly Furtado’s I’m Like A Bird, Migos’s Birds, and the ever haunting Antony and the Johnsons’ Bird Gerhl.

Why are you making commenting on The Herald only available to subscribers?

It should have been a safe space for informed debate, somewhere for readers to discuss issues around the biggest stories of the day, but all too often the below the line comments on most websites have become bogged down by off-topic discussions and abuse.

heraldscotland.com is tackling this problem by allowing only subscribers to comment.

We are doing this to improve the experience for our loyal readers and we believe it will reduce the ability of trolls and troublemakers, who occasionally find their way onto our site, to abuse our journalists and readers. We also hope it will help the comments section fulfil its promise as a part of Scotland's conversation with itself.

We are lucky at The Herald. We are read by an informed, educated readership who can add their knowledge and insights to our stories.

That is invaluable.

We are making the subscriber-only change to support our valued readers, who tell us they don't want the site cluttered up with irrelevant comments, untruths and abuse.

In the past, the journalist’s job was to collect and distribute information to the audience. Technology means that readers can shape a discussion. We look forward to hearing from you on heraldscotland.com

Comments & Moderation

Readers’ comments: You are personally liable for the content of any comments you upload to this website, so please act responsibly. We do not pre-moderate or monitor readers’ comments appearing on our websites, but we do post-moderate in response to complaints we receive or otherwise when a potential problem comes to our attention. You can make a complaint by using the ‘report this post’ link . We may then apply our discretion under the user terms to amend or delete comments.

Post moderation is undertaken full-time 9am-6pm on weekdays, and on a part-time basis outwith those hours.

Read the rules here