THE last time I saw Charlotte Rampling, she was in a bar. It was a Saturday evening in Candelaria, a buzzy little neighbourhood hideaway in the 3rd arrondissement of Paris. As she sipped a glass of wine, the young crowd paid her and her male companion little attention; perhaps too cool to let it be known they’d spotted the British actor. Like her countrywoman Kristin Scott Thomas, Rampling has been adopted by the French as one of their own.

Lately, though, Rampling has been rediscovering her homeland. Already, she’s been seen in series two of ITV’s hugely popular Broadchurch (a role she was awarded after series creator Chris Chibnall saw her in a video art piece by Steve McQueen). In the autumn, she’ll appear in the BBC mini-series London Spy, an espionage drama co-starring Ben Whishaw. And before that comes one of the best British films of 2015, Andrew Haigh’s acclaimed 45 Years, which co-stars Tom Courtenay. “It was a really English year,” she says. “It was just wonderful.”

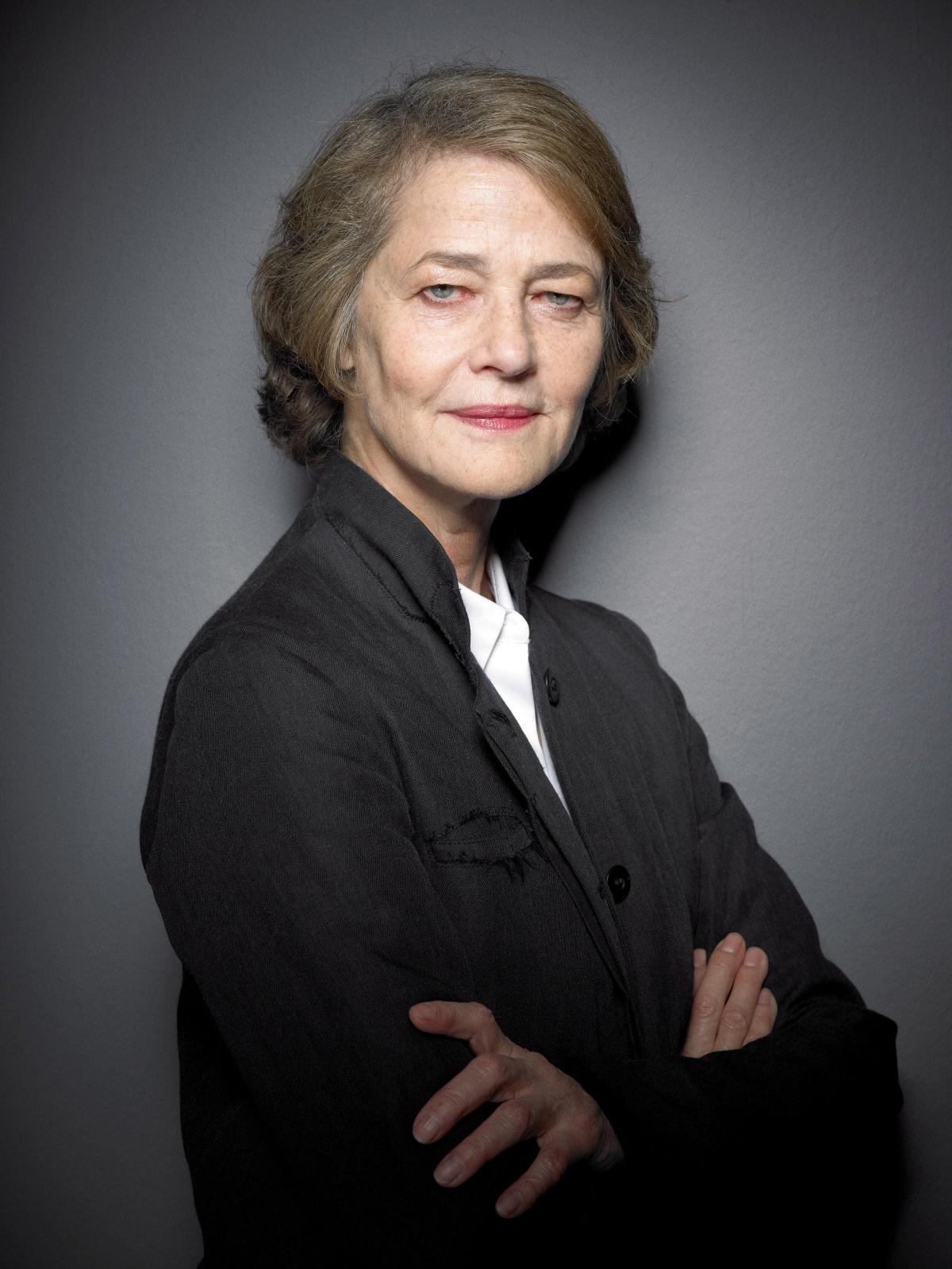

We’re sitting in a white-walled hotel room; Rampling, arriving with her assistant, places her handbag and coat on the sofa next to her. Her hair is styled in a shoulder-length brown bob and she’s wearing black brogues and matching trousers, a beige blouse and a jacket with leather lapels. Next year she turns 70, which seems impossible. Bewitching to behold, if she has aged then she’s done it almost imperceptibly. Her advice? Keep calm and carry on. “You’ve got not to panic, not to be frightened, and not to change your face,” she says. “You need your face to grow with you.” Does she mean plastic surgery? “Yeah, because then people don’t know what age you are. You look a certain age but there is a problem with that, if women can’t live with their faces as they’re growing into them. There’s always a frightening point when your face starts to change, and that’s when you want to change it. But if you go through that change – and it lasts quite a long time, maybe 10 years – then you find actually that you’ve grown into an older face.”

Admittedly, it helps when you’ve been blessed with Rampling’s genes. In 2004, when she was 58, she shot a campaign for fashion designer Marc Jacobs with photographer Juergen Teller, a series of risque self-portraits entitled Louis XV with Rampling de-robed, in bed and giving the camera "the look", that famous stare of hers so-called by her erstwhile co-star Dirk Bogarde. There is a certain spell Rampling seems to cast over her collaborators and her audiences. As Bogarde once wrote, “Charlotte is addictive. Once experienced, she is impossible to forget.”

Even in a deliberately "ordinary" film like 45 Years that’s true. Set in Norfolk, the film is an acutely observed portrait of a long-term marriage. Rampling’s Kate is preparing for a party to celebrate their 45th wedding anniversary when her husband Geoff (Courtenay) receives a disturbing letter, telling him the body of his first love has been found in a glacier in Switzerland, perfectly preserved after she disappeared on a walking holiday five decades previously.

As revelations begin to tumble out of the closet, in Rampling’s eyes the story is about what happens when the extraordinary crashes into everyday existence. “It’s about how we live,” she says. “The trouble Kate has is: how do you get a handle on what you’re feeling about this? You don’t have to be jealous of a dead person. There was no threat. It was before ... He hasn’t got a mistress around the corner, with kids. It’s no big deal. But it becomes this haunting, huge big deal. And that I love. That really fascinated me.”

Written and directed by Andrew Haigh, who previously made the award-winning Weekend, 45 Years is a fascinating look at the secrets and lies that exist in the cracks of relationships. “Men and women are so very different,” says Rampling. “Men have a secret part that a woman can’t penetrate. So when there’s this woman in ice, she’s suddenly taken over.” When Kate needles Geoff to admit that he and his former lover would’ve got married had she not died, Kate begins to question her position in their relationship. “They get very out of control very quickly, those kinds of thoughts.”

Rampling’s own marital history is similarly complex. She was briefly engaged to screenwriter Jeremy Lloyd (the co-creator of Are You Being Served? and ’Allo ’Allo) until her father unceremoniously announced the wedding was off. Later, she married her first husband, her former press agent Bryan Southcombe, in the early 1970s; they had one son, Barnaby (now a filmmaker who directed his mother in the 2012 thriller I, Anna), but the marriage didn’t last. Perhaps Rampling was just too desired by too many.

She was famously pursued by Sean Connery during the making of the bizarre 1974 science-fiction film Zardoz. “He was wildly attractive,” she once said. “He’s a hunter. That’s what he loves.” Then she met French composer Jean Michel Jarre at a dinner party in St Tropez; within a few weeks they were together. Married in 1976, shortly after her divorce to Southcombe was finalised, they had a child – David – the following year. “I learned very early on that Charlotte is not a chatterbox,” Jarre later noted.

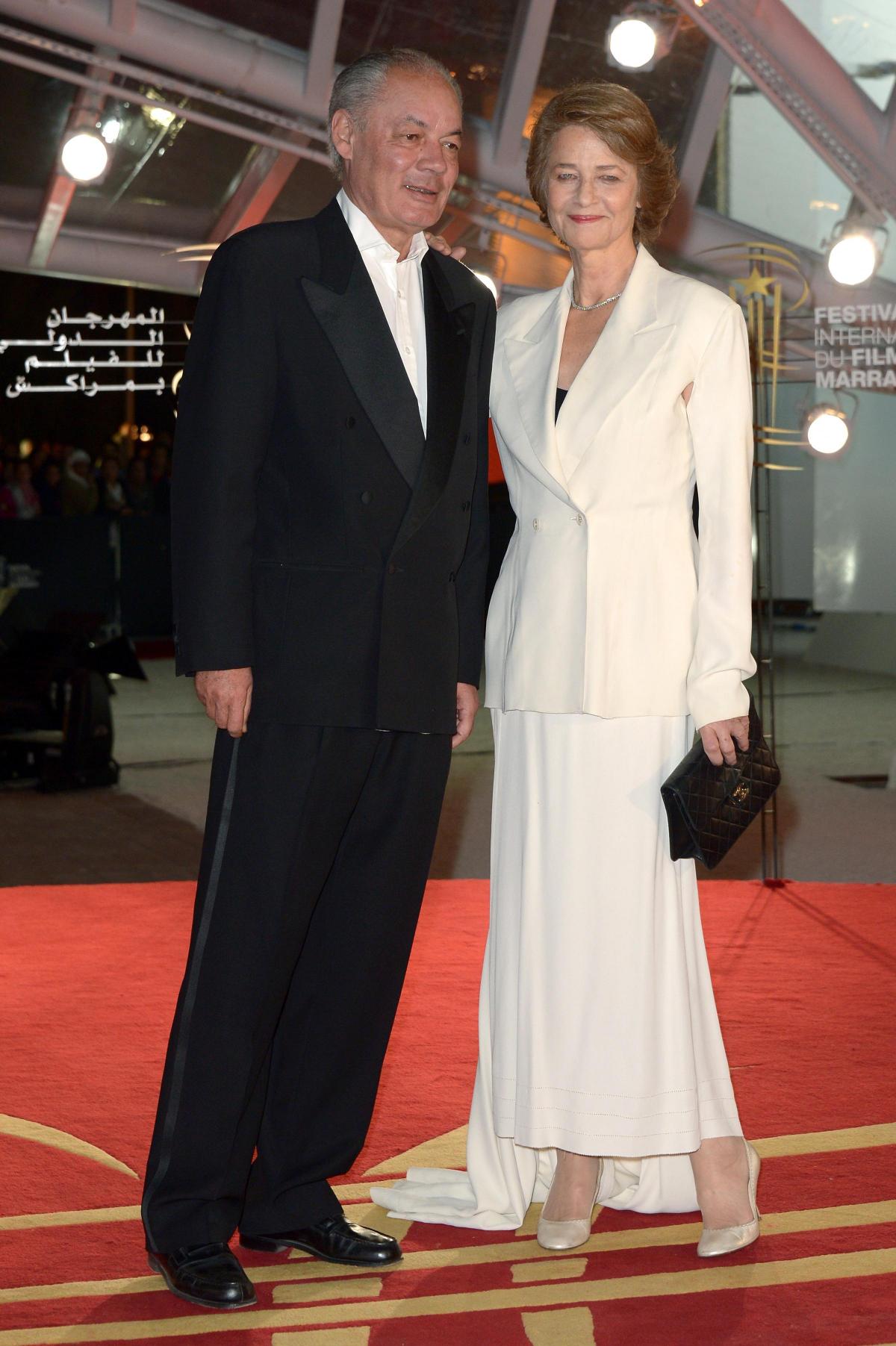

The couple were together for 20 years, but the marriage ended acrimoniously when an affair Jarre had went public. Since then, she’s been engaged to French businessman Jean-Noel Tassez since 1998, which she once joked was “the longest engagement in showbiz”. “[It’s not] because I don’t adore him or anything," she says. "In the end, I just don’t want to be married again.”

Already, 45 Years is shaping up to be one of this year’s surprise contenders in the awards season. At the Berlin Film Festival, Rampling and Courtenay took best actress and actor. In June, at the Edinburgh International Film Festival, where the film won the prestigious Michael Powell award for best British film, she took a share of best performance in a British feature film, alongside James Cosmo for his work in The Pyramid Texts. What if the film featured in this year’s Oscar race (she’s never yet been nominated)? “I’d love it,” she cries. “Could you do something?”

It would certainly be long overdue; aside from an Emmy nomination for the 2012 mini-series Restless, Rampling has been rather overlooked for major awards, both in Britain and the US. Perhaps it’s no coincidence that her best recent work has come in France – notably Swimming Pool, where she was quite brilliant as a tweedy British mystery writer who becomes intrigued by a young French girl. It saw her nominated for a Cesar – one of four times she’s been up for this French equivalent of the Oscars.

More recently, her work with Danish provocateur Lars von Trier and Spain’s Julio Medem intrigued Haigh to cast her in 45 Years. “There’s something really distinct about Charlotte,” he explains. “She’s not in an enormous amount of English films. She spends a lot of her time in Paris and lots of her work is European, and that was interesting to me – I didn’t want to make a twee English film about two old people.”

If 45 Years is partly about the passage of time, and what it does to us both physically and emotionally, Rampling maintains that getting older needn’t be negative. “You’re still as vibrant as you were when you were 20,” she maintains. “The body might be a bit ... the skin and the face ... but all the rest is vibrant. And that’s what growing old is about. It’s lovely to be able to talk about it and show people like that, and for younger people to be able to see you were as passionate and extraordinary as you were when young.”

Experience, she says, is the key. “You don’t have try everything out as you did when you’re young. That’s the only difference. Everything else is the same – if you want it to be the same. So many people just get old ... They think they’re getting old. Just because they’re in their 60s, they go, ‘We can’t do this.’ With Tom [Courtenay], he was a bit like that. I used to bully him all through the film. Whether he’s got better or not, I don’t know. And it is a mindset. It’s really a mindset.”

Partly, says Rampling, making 45 Years stirred old memories, with Norfolk forming part of her childhood. “It felt like a coming-home film,” she says. “My Dad was in the army. We were at Swaffham, which is just next to Norwich.” Her father, Godfrey Rampling, an ex-Olympic sprinter, was a lieutenant-colonel in the Royal Artillery and later worked in the War Office. His work meant the family were never settled anywhere for very long. Rampling spent part of her early years in France, attending the Jeanne d’Arc Academie Pour Jeunes Filles in Versailles, knowing barely a word of French.

Rather strict and old-fashioned, it was her father who stopped Rampling from joining a nightclub as a singer; instead, at 17, she was sent to secretarial school. Ironically, it failed to have the desired effect in her father's eyes when she was spotted working in a typing pool and cast in a Cadbury’s advert. It led to her first role in Richard Lester’s 1965 film The Knack … and How to Get It, swiftly followed by the hedonistic Meredith in Georgy Girl. By now Rampling was a poster girl for the Swinging Sixties.

Life changed in an instant, though, when her elder sister Sarah committed suicide at the age of 23 after giving birth to a premature baby. It was kept a family secret for years, as her father didn’t want Rampling’s mother, Isabel, to discover the real reason. Rampling’s mother, a painter and heiress to the Gurteen Clothing Company, died in 2001, believing Sarah died of a brain haemorrhage. In Rampling’s young eyes, the 1960s were over. “If somebody dies that way," she says, "you don’t feel you can go to a party and have fun.”

Instead, she went on a new journey of self-discovery; by 1969, she’d teamed up with Bogarde for Luchino Visconti’s The Damned, playing a Gestapo victim. Of the great Italian director, she admits: “I didn’t really know who he was when I worked with him, but I sure did find out afterwards. I was 22 at the time. I had an extraordinary relationship with Visconti. I just fell in love with this man – an extraordinary person. I really appreciated it. I knew I was in something special. I did. To start like that, it put me on the way.”

She teamed up with Bogarde again for 1974’s The Night Porter, another SS-themed drama that sent shockwaves through the establishment for its portrayal of a sado-masochistic relationship between an ex-commandant and a concentration camp survivor, played by Rampling. The controversy did little to dent her career: the next decade saw her work with such talents as Robert Mitchum (Farewell, My Lovely), Woody Allen (Stardust Memories), Paul Newman (The Verdict) and, later, Mickey Rourke (Angel Heart).

Was there ever a director that got away? “There was one. It was Fred Zinnemann,” she says. The legendary director of From Here to Eternity and High Noon wanted Rampling for an adaptation of The French Lieutenant’s Woman. “We were going to do it, and the script was there, but he could not find the man. And so it was delayed, and then he had to abandon it. The next year, Karel Reisz took it – and there was a man and who was that? Jeremy Irons. And he took Meryl Streep.”

Rampling was unable to sustain the momentum, partly for personal reasons. Treated for depression in the mid-1980s, she suffered a nervous breakdown in the midst of her marriage to Jarre several years later. Work had all but dried up in America too. “On the other side of the pond, it is difficult,” she shrugs. “I’m not American, so I’m not going to work the American market. But, no, it’s much more interesting from our point of view to be here, that’s for sure. I’ve nothing to do with America. I’m here. This is my world – Europe.”

Rampling was rediscovered in 2000 by French director Francois Ozon, who cast her as a woman whose husband disappears on a beach never to return in Under the Sand. Which was just as well; for years, she’d harboured a dislike of the American studio system, right back to her early 20s. “I didn’t like Hollywood and I didn’t like what they did there. It was stupid. It was a juvenile thing that I had. Years of that – of being bitterly unhappy and hating them all. I was 23 and like, ‘F*** you all. You’re ghastly. I’ll never come back to America.’”

It’s only recently that this opinion has changed, when she was offered a role in Dexter, the US television show starring Michael C Hall as a secret serial killer. Rampling jumped at the chance to play an expert in psychopaths who seems to take a special interest in the title character. “It was a way to reconcile with Hollywood, reconcile with Los Angeles. It seemed a wonderful thing. I said yes so quickly; it was instinctive and I needed to make a decision quite rapidly, and it proved absolutely fantastic. It did me so much good. It jump-started all sorts of things for me.”

Quite whether Rampling will enjoy a late flush in Hollywood, as Dame Judi Dench did, remains to be seen, but she has continued this belated love affair with the US. She’s just shot Waiting for the Miracle to Come, playing one-half of a couple of retired vaudeville stars (the other being played by country singer Willie Nelson). This autumn, she’s back over here, shooting The Sense of an Ending, an adaptation of Julian Barnes’ novel about a divorcee on a quest to retrieve a diary from an old girlfriend.

Our conversation concludes with a typically impassioned answer from Rampling. We’re talking about sexual inequality in film, in life – something Rampling dismisses. “I don’t go for it,” she says. “Women have huge power now.” She fixes those emerald green eyes on me. “What have women got to complain of? In our worlds – I’m not talking about women in countries that are very under-privileged but in our worlds. What have they got to complain about? It shouldn’t be a thing. I think it’s inappropriate.”

45 Years (15) opens on Friday.

Why are you making commenting on The Herald only available to subscribers?

It should have been a safe space for informed debate, somewhere for readers to discuss issues around the biggest stories of the day, but all too often the below the line comments on most websites have become bogged down by off-topic discussions and abuse.

heraldscotland.com is tackling this problem by allowing only subscribers to comment.

We are doing this to improve the experience for our loyal readers and we believe it will reduce the ability of trolls and troublemakers, who occasionally find their way onto our site, to abuse our journalists and readers. We also hope it will help the comments section fulfil its promise as a part of Scotland's conversation with itself.

We are lucky at The Herald. We are read by an informed, educated readership who can add their knowledge and insights to our stories.

That is invaluable.

We are making the subscriber-only change to support our valued readers, who tell us they don't want the site cluttered up with irrelevant comments, untruths and abuse.

In the past, the journalist’s job was to collect and distribute information to the audience. Technology means that readers can shape a discussion. We look forward to hearing from you on heraldscotland.com

Comments & Moderation

Readers’ comments: You are personally liable for the content of any comments you upload to this website, so please act responsibly. We do not pre-moderate or monitor readers’ comments appearing on our websites, but we do post-moderate in response to complaints we receive or otherwise when a potential problem comes to our attention. You can make a complaint by using the ‘report this post’ link . We may then apply our discretion under the user terms to amend or delete comments.

Post moderation is undertaken full-time 9am-6pm on weekdays, and on a part-time basis outwith those hours.

Read the rules hereLast Updated:

Report this comment Cancel