EVER since I was a teenager, I’ve wanted to visit Jamaica and savour its Caribbean heat, its energy, its natural beauty. The exuberance and musical audacity of reggae has been a constant in my life and Jamaican culture always seemed so self-assured that I craved to experience it first-hand.

Last year I read Professor Tom Devine’s history of the Scottish diaspora, To The Ends Of The Earth, and was stunned to discover that Jamaica had a disturbing historic link with our shores. During the 18th and 19th century when slavery was the dominant economic force, many of the island's sugar plantations were operated and owned by Scots. None of this had been in the economic history syllabus I studied at university; instead the Scottish role in the eventual emancipation of slaves was the more resonant tale in the classroom.

According to Devine, not only had Scottish planters in Jamaica bought thousands of slaves straight off the boat and put them to back-breaking work in the sugar cane fields, but the huge profits they made in the process had boosted the Scottish economy. Our ancestors back home obtained cheap sugar from the Caribbean to sweeten tea and provide energy-laden foods while the massive profits that flowed from the West Indies turbo-charged Scottish industries such as fishing, weaving, railways and mining. In addition, huge country estates, mansions and even schools were built all over Scotland with the filthy lucre that slaves generated for nearly 150 years in the hot Caribbean sun.

A year ago, with the referendum looming large in the national psyche and our collective values being rightly scrutinised, I couldn’t help wondering how we had conspired to forget this episode in our history. As I read more on the subject from tenacious historians like Eric Graham, Sir Geoff Palmer and Stephen Mullen, who have been filling in the gaps in our knowledge, I began to wonder if there might be an opportunity for me to visit Jamaica and use my camera to add a layer of evidential imagery to what they have uncovered about Scotland’s role in the era of mass slavery.

Then the Scottish National Portrait Gallery asked Document Scotland, a photography collective to which I belong, to produce a series of works in response to the aftermath of the referendum for an exhibition this month, one year on from the historic vote.

Having photographed all over Scotland in the run-up to the referendum, I was keen to reflect on our national story through the prism of a foreign land, especially one that had just celebrated 50 years of independence from Britain. Could I find a way to link the little-known backstory of Scotland's role in the troubling history of slavery in colonial Jamaica with our present?

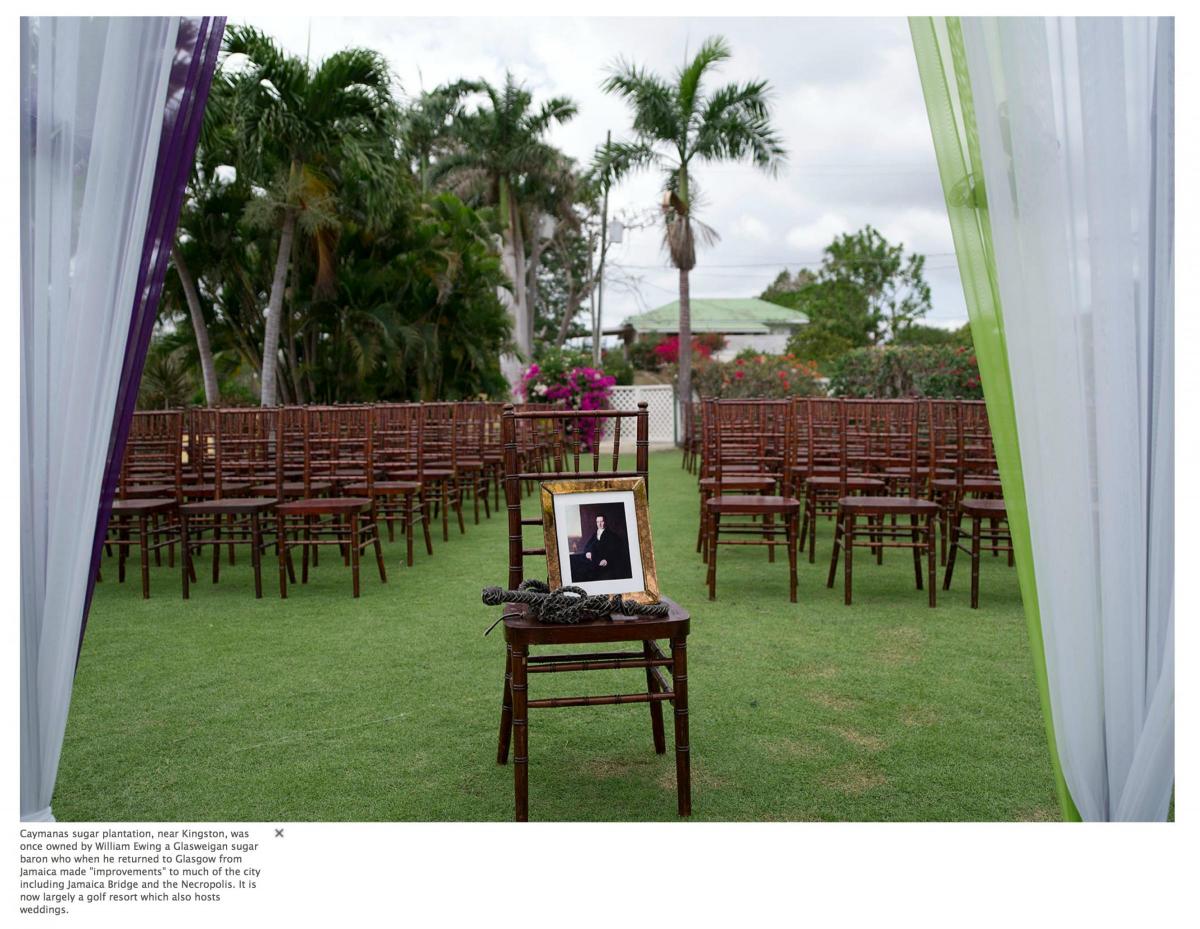

As a starting-point I wanted to see for myself what impact Scotland of the 18th and 19th century had made on this large island of nearly three million people who are world-renowned for their warm welcome and vivacious national identity. Many Jamaicans and Britons of Jamaican descent like Naomi Campbell and reggae star, Peter Tosh (Mackintosh) have Scottish surnames so I knew it would be interesting to explore the genealogical legacy of this period, but I wanted to go beyond that. I wanted to photograph the land which had once been owned by rich Scots and see what remained of the great houses they had built for themselves and from where they could gaze down upon their slaves toiling in the fields. In addition I wanted to return home and photograph how the vast profits from the slave economy in Jamaica have left their mark on Scotland.

In spring of this year I was planning a photography trip to Jamaica and researching historical figures who left home in the 1700s to embark on a journey across the Atlantic in pursuit of great wealth. Historians in both Scotland and Jamaica were generous in giving me leads, but it was a conversation with Fife-based novelist, James Robertson that turned my own journey into something altogether more intriguing.

Robertson's Saltire Prize-winning novel, Joseph Knight, tells the story of a rich Scot, John Wedderburn, and his brothers, who left for Jamaica soon after the Jacobite rebellion of 1745. Wedderburn’s father had fought under the Great Pretender at Culloden, and paid for it by being hung, drawn and quartered at Kennington Common in London. That's what rebellion against the Crown got you in those days and it was hardly surprising that the Wedderburn boys fled Scotland to try and make a living far away from where family allegiances might have held them back. In Jamaica they first trained as doctors then bought land with the aim of growing sugar. Despite coming from a relatively egalitarian and God-fearing society, the need for slaves to work their land doesn’t seem to have been too much of a moral quandary and in a short time they came to own several plantations with hundreds of Africans cutting cane and boiling sugar before having it transported back to Britain in the same ships that would have also delivered forced labour from Africa.

Robertson’s novel is a page-turner and a sick-to-the-stomach indictment of the savage conditions that underpinned the sugar trade, but the most incredible aspect of it is that it is based on a true story. The eponymous Joseph Knight was an African slave employed as a valet to John Wedderburn on his plantation, Glen Isla. Scottish legal records reveal that in 1777 Knight – named after the ship’s captain who sold him as a slave – travelled to Scotland as John Wedderburn’s butler and later successfully sued for his freedom at the Court of Session in Edinburgh, creating a precedent that outlawed slavery in Scotland several decades before the UK parliament emancipated slaves in the British Empire.

Glen Isla lies about eight miles inland from the south-coast Jamaica town of Savanna-La-Mar. James Robertson visited the location while researching the novel and his evocative descriptions of the area's topology conjure up the sights, smells and noises of this corner of rural Jamaica. I was determined to visit Glen Isla myself but it is so small that it doesn’t feature on any Google Earth map, so I asked Robertson for directions to the plantation itself. Thanks to his keen recollection of place and scenery I found myself driving a hire car up some perilously unmaintained roads, past makeshift houses with zinc roofs and walls, to the top of a green hill where the Glen Islay Seventh Day Adventist Church stood. Despite the obvious poverty that pervades the area it is a beautiful place with dense tropical foliage and waterfalls. Hardly surprising then that the Wedderburns named it after a picturesque Scottish glen close to where they grew up.

Sugar cane is still grown on the plain beneath Glen Isla but the plantation house that John Wedderburn would have inhabited on the cooling hillside has long disappeared. As you look out through the misty vegetation down towards the cane fields it is hard not to think of Joseph Knight, dutifully working in the big house for his master. Did he have any inkling that he would go on to make legal history in Scotland with a cause celebre that in its time prompted Edinburgh Enlightenment figures such James Boswell and Lord Kames to wade into the legal arguments?

The local people I spoke to knew the land used to be one huge sugar plantation but didn’t know that it was named after a small Scottish glen. Indeed, Jamaicans who live in towns called Inverness, Roxborough and most-poignantly, Culloden, seem generally unaware that their towns were named after places in Scotland.

Around 1769, Joseph Knight sailed with John Wedderburn for Scotland. It must have been terrifying to make another transatlantic voyage after the one that had brought him to Jamaica in chains. Wedderburn, a very rich man thanks to Britain’s insatiable appetite for sugar, was determined to return to his homeland and acquire the life of a respectable gentleman in Hanoverian North Britain. Having left under a post-Culloden cloud he wanted to regain the family prestige that had made the Wedderburns near-nobility prior to 1745. He returned looking to settle down and remind Scottish society that he and his family were people of great stature, the 6th Baronet of Blackness, no less. There was also the question of finding a wife who would help ease his way back into polite society, and of course with a young black manservant he would no doubt be talk o’ the toon.

Back in Scotland, I visited Ballendean House in Perthshire, the large country pile that John Wedderburn bought on his return. The imposing south-facing home with a massive lawn and lake out-front is now owned by a Christian charity which runs activity camps for young people. On the Sunday I visited I was greeted by the surreal sight of the Dundee Hurricanes American Football Team practising on the main lawn. Joseph Knight spent several years at Ballendean before summoning the courage to run away and begin petitioning for his freedom. Walking around the property you can imagine how rootless he must have felt among Perthshire high-society where his status was an ornament, or worse, an exotic pet.

While many colonists perished pursuing their get-rich schemes, others endured the stifling heat and tropical illnesses, sustained by their dreams of a triumphant and wealthy return. As most travelled to Jamaica without wives, another aspect of their lives has gone largely unspoken. Many Scots plantation owners treated their female African slaves as property to do with as they pleased. Some of the many mixed-race children that resulted were given their freedom but many more remained slaves.

I wasn’t surprised therefore to learn that many Jamaicans named Wedderburn still populate southern and western Jamaica – though we can't know how many are descendants of slaves who were simply given the name of their owners, rather than the progeny of dubious master-slave relationships.

Surnames remain a sensitive topic in Jamaica. How could it not be when slaves were banished from keeping their original names and were given names, often comedic or infantile, by their owners? Many Rastafarians have taken new African names as a way of refusing to acknowledge the dominating power of slavery through the centuries. It should also be noted that many Scots came to Jamaica as missionaries and doctors, and put down roots without owning slaves. When I met reggae and rock musician, Wayne McGregor, in Kingston, I was unsure how to broach the subject of how his family had come by his surname, but when he showed me the Celtic tattoo on his shoulder it became apparent that he was at ease with the Scottish legacy in his genealogy.

“As a child I was always interested in our family background and I would get a profound sense of history and Celtic belonging in a sense when told of how 'Old Man McGregor' and his brothers came to Jamaica and fell in love with the country and the ladies. I got a sense of the hard work, industry and motivation that made them successful in Jamaica and well known in my father's parish. As I grew older, I realised this background knowledge made me feel like a more rounded Jamaican, especially given the fact that many Jamaicans have no idea about the origin of their surnames nor the people that passed said names down to them. As an adult, I developed a sense of pride in all aspects of my background, regardless of where such background elements may hail from.”

Diana Macaulay, an award-winning author and founder of the Jamaica Environment Trust, a pressure group for maintaining the island’s natural landscapes. Her novel, Huracan, intertwines several stories of Scots who came to Jamaica looking for a new beginning, whether as a plantation bookkeeper or as a missionary. Indeed, Macaulay thought her ancestor might have been a 19th century missionary to Jamaica and when she journeyed to the Mitchell Library in Glasgow a few years ago she found evidence that her great great grandfather, John Macaualy had sailed for the West Indies in 1884 as a steamships fireman and when in Jamaica became a missionary and put down roots.

Macaulay’s recollections from her trip to Glasgow were illuminating: “Although Glasgow was made rich by sugar and tobacco and that great wealth is still evident in lavish buildings; in general, the Scots have felt slavery was an English crime because they were less directly involved in the trafficking of human beings. But the Scots flocked to the West Indies and they made money in many trades and occupations created by the sugar plantations, made possible by slavery – in 1774, according to historian Edward Long, one-third of the white population in Jamaica was Scottish.”

If we are to be a nation at ease with itself we need to be honest about who we are and where we’ve been. The good and the bad. There's no point denying our role in slavery and indeed, shouldn’t we be in dialogue with the Caribbean nations to ask how we can make amends for this period? Our economy benefited hugely from this colonial episode and although many Scots were pioneers in the campaign for emancipation, we also had huge vested interests and politicians who ensured that slavery continued for much longer than it should have done. Jamaica has not forgotten slavery, far from it, but it has reckoned with it, and this is something that Scotland needs to do.

A Sweet Forgetting is being exhibited as part of Document Scotland’s The Ties That Bind photography exhibition, which runs at the Scottish National Portrait Gallery, Edinburgh until April 26

Why are you making commenting on The Herald only available to subscribers?

It should have been a safe space for informed debate, somewhere for readers to discuss issues around the biggest stories of the day, but all too often the below the line comments on most websites have become bogged down by off-topic discussions and abuse.

heraldscotland.com is tackling this problem by allowing only subscribers to comment.

We are doing this to improve the experience for our loyal readers and we believe it will reduce the ability of trolls and troublemakers, who occasionally find their way onto our site, to abuse our journalists and readers. We also hope it will help the comments section fulfil its promise as a part of Scotland's conversation with itself.

We are lucky at The Herald. We are read by an informed, educated readership who can add their knowledge and insights to our stories.

That is invaluable.

We are making the subscriber-only change to support our valued readers, who tell us they don't want the site cluttered up with irrelevant comments, untruths and abuse.

In the past, the journalist’s job was to collect and distribute information to the audience. Technology means that readers can shape a discussion. We look forward to hearing from you on heraldscotland.com

Comments & Moderation

Readers’ comments: You are personally liable for the content of any comments you upload to this website, so please act responsibly. We do not pre-moderate or monitor readers’ comments appearing on our websites, but we do post-moderate in response to complaints we receive or otherwise when a potential problem comes to our attention. You can make a complaint by using the ‘report this post’ link . We may then apply our discretion under the user terms to amend or delete comments.

Post moderation is undertaken full-time 9am-6pm on weekdays, and on a part-time basis outwith those hours.

Read the rules here