There is a long and venerable – if controversial – history of erasure in art. From Renaissance masters rubbing at oils to remove and reapply, to art restorers scraping away “superfluous” layers of paint; from Robert Rauschenberg, who used 40 rubbers to erase a de Kooning drawing in “Erased de Kooning” in the 1950s to Jonathan Owen's contemporary Eraser Drawings, artists have long experimented with taking something away to produce something new. The permutations are complex, from simple necessity to a rejection of the past, from the rebuttal of received learning and inheritance, to the idea that we can only create something new by studying then rubbing away the old. What is left, if we take everything else away?

In portraiture this is no less relevant. Artist Audrey Grant uses erasure as a key part of her process in working towards a portrait, as shown in this fascinating new exhibition at the Scottish National Portrait Gallery. It began, says the photographer Norman McBeath, subject of one of the series of portraits in the show, when Grant asked him to sit for her in 2015. What resulted was a long process of sittings, in which McBeath was looking as much as Grant, each inspecting the other from the intimacy and formality of the artist-sitter relationship. McBeath was not the passive sitter, stock still, attempting to hold the pose – although there was doubtless an element involved – but a sitter who looked back, increasingly actively, evolving the process as the years went by.

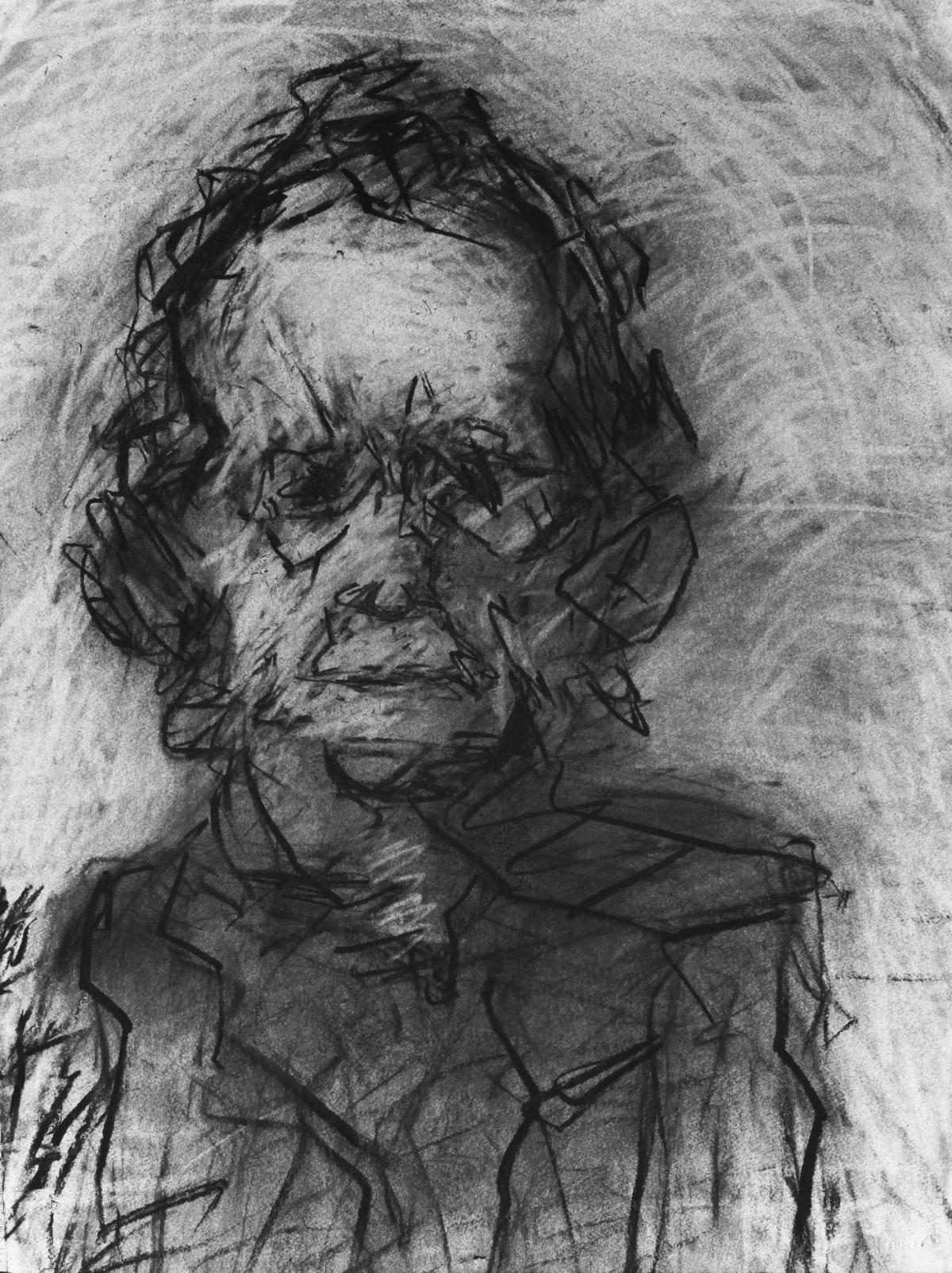

Before each sitting, Grant would take up her eraser and rub out all but the faintest traces of the image which she had spent hours creating. Working in charcoal on thick paper, Grant had recalled the work of Frank Auerbach, who had himself, in his “Portrait of Sandra” (1973 – 74) created a series of 40 drawings, working, erasing, reworking and finally producing the finished painting. Grant's own process was of 36 drawings, each recorded by McBeath, a symbiotic relationship which developed in the early stages of the sitting, McBeath as fascinated by the process as Grant.

It led to McBeath's own “portrait” of Grant, a series of images, not simply of the drawings which she then assiduously erased at the beginning of each sitting, but of the process itself. It was the noise, McBeath says in the fascinating catalogue that accompanies the exhibition, that first brought his attention away from what he had thought might just be “a chance for a bit more thought in the midst of a busy life.” “Lots of scraping sounds on the paper, a lot of movement from you [Grant], charcoal splintering on to the floor and rapid footsteps to and from the easel. All of this caught my imagination, so much so that the idea of being just passive vanished entirely.”

The result are detailed images of Grants charcoaled hands (taken at the end of each sitting) shiny with charcoal dust, of used finger tape, of her paint-spattered shoes and apron, of the sticks of charcoal themselves.

The second subject – or third, rather – was the crime writer Val McDermid, caught in Grant's smudged, forthright, marked-up charcoals. McDermid says she spent nearly 100 hours sitting in the basket chair in Grant's studio, listening to the evocative sounds – not unsettling but provoking reverie - of her likeness being caught, pinned down, on paper. Where McBeath started to look back at Grant, McDermid used the time to look within, to think of ideas for the next book in the rare hours in which she was not required to be doing anything else but staying still.

Grant's own process, of the many and long sittings, is one of building up a familiarity with her subject, although likeness, she says, comes more “in the early stages of the drawing,” in the images which she has rubbed out and then drawn over. What she is after is that which is not at first glimpsed. What she creates is the sense of a background, of the parts of the sitter, of any person, which are not seen or seen only with blurred vision, those discrete parts of the self that are never fully revealed, and the different faces which present themselves of something which can never quite be known.

“All those ghosts,” says Grant, in conversation with McBeath, “existed once, if only for a short time, but they still haunt the final drawing which I hope will express something honest about the sitter.”

The Long Look, Scottish National Portrait Gallery, 1 Queen Street, Edinburgh, 0131 624 6200, www.nationalgalleries.org, Until 27 Oct, Daily, 10am – 5pm, Admission Free

Critic's Choice

As part of a year of exhibitions highlighting craft artists exploring topical issues, An Tobar opens its summer exhibition this week with Lucy Woodley's Ultima Thule. The reference to the classical idea of a mythical land somewhere beyond the edge of the known world, and the idea of the farthest point of any given journey, is here used to throw the issue of migration into relief.

Woodley is concerned, here, with the narratives that surround the movement of peoples, particularly inspired by the terrifying stories and uncertain outcomes of modern journeys, frequently made across the seas that divide us in small boats. Her background is in Jewellery – she graduated from Grays School of Art, Aberdeen, in 1992 – but after 20 years in business as a jeweller, Woodley has recently moved in to sculpture, applying a jeweller's attention to fine detail to her installations.

The works are stark, simple, beautiful, each containing minimal elements – a bird, a boat, tiny silver fish. The colours are monochromatic, with subtle flashes of red or orange. Using silver and found objects, Woodley maroons her silver boats on rocks, on branches, suspends them between continents, between the rafters of a house, captive, arrived but unable to disembark.

“Our world is in flux,” says Woodley. “We are being forced into reconfiguring our borders and along with them our identities. Ultima Thule is my way of exploring the themes around migration, the hope and the trepidation that comes with any journey that traverses known and unknown territories.”

Lucy Woodley: Ultima Thule, An Tobar, Argyll Terrace, Tobermory, Isle of Mull, 01688 302211 www.comar.co.uk Until 9 Aug, Tues – Sat, 11am – 5pm, Tonight - Opening night, 6pm – 8pm, all welcome.

Don't Miss

Daniel Lie's monumental organic installations at sculpture park, Jupiter Artland, have been in position for a couple of weeks now, meaning that the funghi and other organisms for which the artist has provided habitats for colonisation will doubtless be in the early throes of blooming. Those who visited in the first weekend will have seen the first frills of the pink oyster mushrooms in the Stable Gallery poking their way out of their plastic sacking, and signs of other funghi, arrived, unseen. Around them, the other organic materials will be wilting, degrading, ensuring these symbiotic installations are ever-changing, evolving, living, dying, until the exhibit closes in July. Do go.

The Negative Years: Daniel Lie, Jupiter Artland, Bonnington House Steadings, Near Wilkieston, 01506 889900 www.jupiterartland.org,Until 14 July, Daily 10am - 5pm

Why are you making commenting on The Herald only available to subscribers?

It should have been a safe space for informed debate, somewhere for readers to discuss issues around the biggest stories of the day, but all too often the below the line comments on most websites have become bogged down by off-topic discussions and abuse.

heraldscotland.com is tackling this problem by allowing only subscribers to comment.

We are doing this to improve the experience for our loyal readers and we believe it will reduce the ability of trolls and troublemakers, who occasionally find their way onto our site, to abuse our journalists and readers. We also hope it will help the comments section fulfil its promise as a part of Scotland's conversation with itself.

We are lucky at The Herald. We are read by an informed, educated readership who can add their knowledge and insights to our stories.

That is invaluable.

We are making the subscriber-only change to support our valued readers, who tell us they don't want the site cluttered up with irrelevant comments, untruths and abuse.

In the past, the journalist’s job was to collect and distribute information to the audience. Technology means that readers can shape a discussion. We look forward to hearing from you on heraldscotland.com

Comments & Moderation

Readers’ comments: You are personally liable for the content of any comments you upload to this website, so please act responsibly. We do not pre-moderate or monitor readers’ comments appearing on our websites, but we do post-moderate in response to complaints we receive or otherwise when a potential problem comes to our attention. You can make a complaint by using the ‘report this post’ link . We may then apply our discretion under the user terms to amend or delete comments.

Post moderation is undertaken full-time 9am-6pm on weekdays, and on a part-time basis outwith those hours.

Read the rules here