Pozzuoli, Napoli, 1932

‘Carlo! Carlo! Aspetta! Wait for me!’

Ninuccia sounded slightly distressed. Carlo glanced back to see where she was. He caught sight of her far below, the parcel wrapped in newspapers tightly grasped to her chest as she lifted her short legs to climb each step. Her dark curls were dripping with sweat. She called again, louder.

‘Carlo!’

He waved to her, frustrated, encouraging her to hurry.

‘Ninuccia’! Forza!’

Two women scrubbing clothes at the water fountain watched the scene unfold. They reproached him, laughing.

‘Carlo’! Wait for her! She’s only three. Poveretta!’

Carlo shrugged his shoulders, flashed an amiable smile and ran on barefoot up the steps. Ninuccia would take too long to climb up the steps to get home. She’d arrive when she did. He couldn’t wait; he was too hungry. His sister’s calls faded in the distance.

Everyone knew Carlo in the Rione Terra. He was Annunziata’s son.

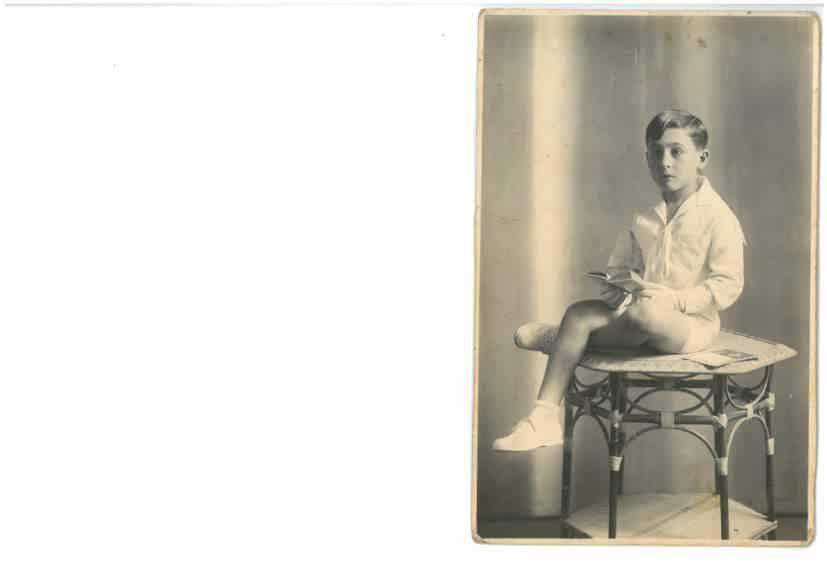

He was a good-looking boy, taller than average for his seven years, fair-skinned with thick blond hair. His large, dark, almond-shaped eyes filled his aquiline face; his sweet cherub lips lit up his face when he smiled.

Everyone knew Carlo because Carlo knew everyone! He never passed without a call of greeting, a quick word of encouragement or a nod of interest. He had the uncanny knack of seeing everyone as a person, an individual; a fortunate talent. The two women had known him since he was born, but it was as if he had known them before they were born.

Swinging a brown paper parcel tied with string, he skipped up the narrow vicoletto, counting the hundred and seventy eight steps to reach home. It was almost midday and the shaded alleyway was gratifyingly cool in the summer heat. An occasional a shaft of light cut through the gloom and lit the way.

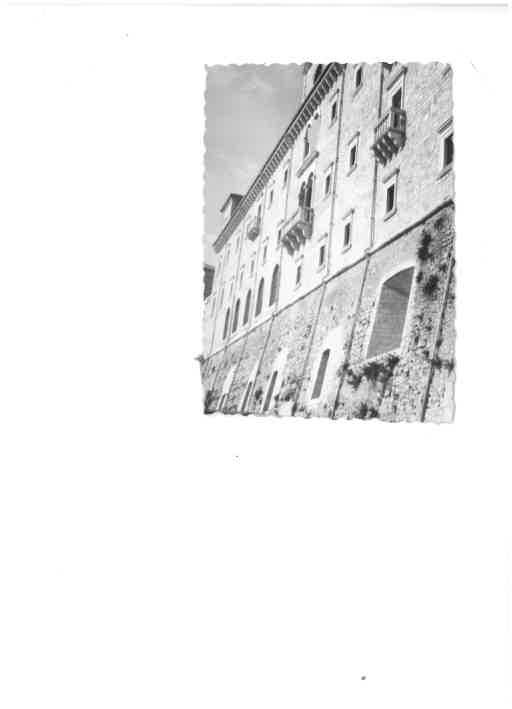

The buildings on either side of the steps were four and five stories high, jumbled and haphazard, so close together that people leaned out and spoke to each other from balcony to balcony as if in the same room. Washing hung shamelessly between the houses creating a spectacle of underwear, slips and vests; towels, sheets and tablecloths. An endless cascade of children’s clothes, hung outside narrow balconies in ever decreasing order.

On every door step, women huddled together in twos and threes, their aprons pulled up onto their laps, full of vegetables to prepare for the midday meal; long mottled borlotti beans, fresh pods of pea green piselli or bunches of leafy green friarielli. To help keep the backs of their necks cool, their dark hair was piled up and tied back with coloured rags, their bronzed faces flushed. Their dark eyes darting from face to face, engaging in the animated Puteolana dialect, enjoying una bella chiacchierata as they podded, topped and tailed the vegetables. They tossed the speckled beans and vibrant leaves into a bowl, the stalks and empty pods discarded casually onto the steps.

Other women were darning clothes or carefully embroidering pieces of lace, neither fingers nor tongues ever idle. Ragged children of all ages, barefoot and hatless, ran up and down the steps shouting and laughing or sitting in huddles, miniature imitations of their mothers and aunts, gossiping intently themselves.

There was not an inch of space spare, a centimetre unused. Most families lived in one room, a dozen or more people together, little space for furniture other than a table, some chairs and a bed. There was no such thing as privacy; everyone knew everyone’s business. Windows and doors were thrown open all day so that conversations, arguments and loving were heard by all.

Life spilled out into the alley, the opportunity of space and fresh air jealously enjoyed. The street was their living room. Every morning, on every available spot, tables were carried out, covered with anything to hand, a sheet of newspaper or an embroidered tablecloth. A random selection of odd cutlery, plates and glasses were laid, a candle or lamp, a jug of water, a fiasco of wine, ready, anticipating the next mealtime. Toothless ancient, great grandmothers, too old to help, were already perched at tables, observing the goings on, patiently waiting to eat. Groups of grandfathers sat absorbed playing Briscola together, cool in sleeveless vests, their large bellies a sign of comfort and success to their wives and mistresses.

The people of il Rione Terra had very little; they expected very little. The ancient fortified settlement perched above the Bay of Pozzuoli, a four-hour walk along the coast, north of Naples. The continuously gasping Vesuvius menacingly loomed over them. Blessed with the sun, the sea and an appreciation of life’s brevity they lived intense, immediate lives.

A contented woman, Carlo’s mother constantly repeated her mantra to Carlo: ‘My son, all you need is to eat, drink and wash your face!’

He agreed with that, though was not so interested, at this stage, in washing his face.

As he climbed the steps smells of cooking lingered in the air. He took deep breaths, savouring the flavour of each scent; luscious fresh tomatoes softening into sugo with green oil and aromatic basil; creamy onions sweetly sizzling in olive oil; pungent sardines blackening on a grill; a sharp whiff of singed garlic and pepperoncino making him salivate. He loitered a moment to indulge in the aromas, his hunger knotting his stomach. Judiciously he remembered his sister; she had the food.

He cupped his hand over his mouth and called down the steps, yelling to her to get a move on,

‘Ninuccia’! Ninnuuccia’! …Forza! ’

‘I’m coming, Carlo,’ she called back.

Jumping over a sleeping tom cat, he swung around some scraggy chickens pecking in the dust. He nodded ‘buon giorno’ to Giuseppe, the one legged beggar who always sunned himself in the pool of sunshine at the corner of his uncle, Zio Alfonso’s cobbler shop.

‘Bravo, Giuseppe,’ thought Carlo, ‘if you need to beg, you may as well beg in the sun.’

He admired Giuseppe; he was always at his corner, every day, whatever the weather.

‘No matter your job,’ Carlo observed, ‘you need to put in the hours.’

Extract from Dear Alfonso by Mary Contini

Special offer for Herald Readers

Receive a free, signed copy of Dear Alfonso when you place an order on valvonacrolla.com. Minimum order £40

Why are you making commenting on The Herald only available to subscribers?

It should have been a safe space for informed debate, somewhere for readers to discuss issues around the biggest stories of the day, but all too often the below the line comments on most websites have become bogged down by off-topic discussions and abuse.

heraldscotland.com is tackling this problem by allowing only subscribers to comment.

We are doing this to improve the experience for our loyal readers and we believe it will reduce the ability of trolls and troublemakers, who occasionally find their way onto our site, to abuse our journalists and readers. We also hope it will help the comments section fulfil its promise as a part of Scotland's conversation with itself.

We are lucky at The Herald. We are read by an informed, educated readership who can add their knowledge and insights to our stories.

That is invaluable.

We are making the subscriber-only change to support our valued readers, who tell us they don't want the site cluttered up with irrelevant comments, untruths and abuse.

In the past, the journalist’s job was to collect and distribute information to the audience. Technology means that readers can shape a discussion. We look forward to hearing from you on heraldscotland.com

Comments & Moderation

Readers’ comments: You are personally liable for the content of any comments you upload to this website, so please act responsibly. We do not pre-moderate or monitor readers’ comments appearing on our websites, but we do post-moderate in response to complaints we receive or otherwise when a potential problem comes to our attention. You can make a complaint by using the ‘report this post’ link . We may then apply our discretion under the user terms to amend or delete comments.

Post moderation is undertaken full-time 9am-6pm on weekdays, and on a part-time basis outwith those hours.

Read the rules here