IT'S a quarter of a century now since rave culture waved its translucent glow stick at the world, the police and the notorious Criminal Justice and Public Order Act. There hasn't been a significant youth movement since - and no, Britpop doesn't count - and much has been written and said about why that should be.

Sociologists, cultural historians, those who were there at the time and those who think they might have been but don't remember too well have all chipped in their tuppence-worth. But the prize for the most succinct appraisal of this sad state of affairs goes to the music blogger who wrote simply: “Subculture as we know it is dead and it's all the internet's fault.”

Many would agree with both the diagnosis and the alleged culprit. Music and fashion are still a potent mix, but we live in an age when any street-level subculture based around them will have been co-opted to the cause of some or other pop star before you can say the words “celebrity stylist with a million followers on Instagram”. Or words like them.

Moreover, fashion today is such a churning sea of references and retro influences that most people barely have enough time to post a selfie before they're on to a new look. As for assembling those new looks, anything and everything is available at the touch of an iPad. Buy it today and you can have it tomorrow – and the charity shop can have it a week later. It's all too easy.

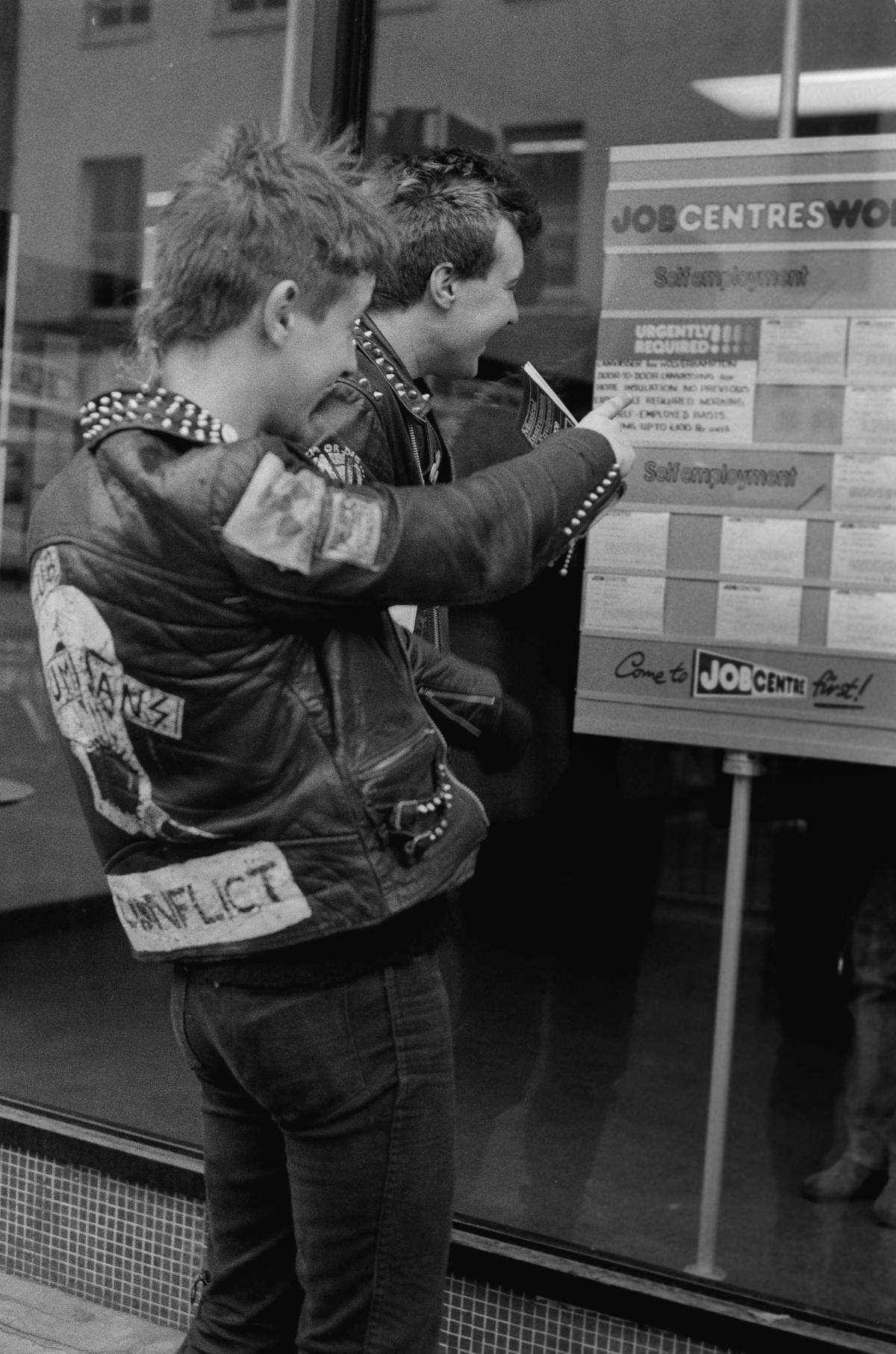

This isn't a fairy story, but once upon a time things were very different. For over three decades, from the late 1950s until the early 1990s, youth subcultures thrived in the UK, many of them underground and all of them requiring dedication, time and commitment.

With the exception of football casuals, all of them formed around types of music such as Ska, Rockabilly, Punk, Glam Rock or Northern Soul, and each had its preferred labels or styles. The subcultures developed, percolated and spread slowly as young people came together in clubs, cafes and record shops to eye each other's clobber, swap music and fashion tips, find a collective sense of identity and stick to it. It's exactly that which is the subject of Shane Meadows's film This Is England and its subsequent TV manifestations.

Each group had its own arcane dress codes and many required close attention to detail. And I mean close: for the Southern Soulboys of the early 1970s, a v-neck mohair sweater was de rigueur. But the hardcore scenester would know whether or not it came from Acme Attractions on London's King's Road. If it did, kudos to you. Likewise the Soulboys' Suedehead cousins could tell whether or not a button-down shirt was Jaytex or some inferior imitation.

Other subcultures in other years would have asked similar questions. Are those brothel creepers by Denson? Is that a genuine Baracuta G9 or just a knock-off Harrington from a market stall? Is that Iron Cross on your Hells Angels jacket real?

In The Bag I'm In, a lovingly-assembled book about music and fashion and the subcultures they spawned, collector and clothes obsessive Sam Knee catalogues all of this, throwing a net over three decades of youth fashion tribes and hauling in an inestimable prize in the form of photo booth snaps, Polaroids and grainy Kodak Instamatic images.

Knee begins his tale in 1960 with a chapter on Rockers. Then he works his way chronologically through those other seismic youthquakes, Mod and Punk, as well as sub-genres like Hard Mod, Anarcho-Punk and Post-Punk. He delves into the Skinhead, Art School Boho and Space Rock scenes, charts the Rockabilly and Mod revivals of the early 1980s and even has chapters on Pub Rock and Medway Garage, a Kent-specific scene.

He doesn't neglect other regions and nations either. Northern Soul is an important part of that story, as is the explosion of talent thrown up in Glasgow and Edinburgh at the other end of the 1970s. Knee calls this The Postcard Look after the name of the Glasgow-based label which signed bands such as Josef K and Orange Juice. Still in Scotland, his chapter on Indie opens with a quote from a song by The Jesus And Mary Chain and features early pictures of them, The Pastels, The Vaselines and a disturbingly young-looking Bobby Gillespie, who has also penned an introduction to The Bag I'm In.

Eventually we wind up in Manchester with what Knee calls Baggy - or Madchester as it's sometimes known after the trailblazing bands who fused dance culture with indie rock music in the city in the late 1980s. Then, at 1990, he stops. Why?

“I see it as the cut-off year, as all the UK-derived indie guitar scenes had reached their logical conclusions, stylistically and musically,” he says. “The period between 1960 and 1990 is the ultimate youth tribes timeline, spanning the pacy golden eras when underground scenes were genuinely underground, self-sufficient, offering a way out from mainstream society.”

Does he agree, then, that subculture is dead? Up to a point.

“Underground youth fashion music scenes of this fevered, life-depending intensity were very much a 20th-century phenomenon and unlikely to occur again anytime soon,” he admits. “The internet has caused a blanketing standardization on society where scenes struggle to grow organically in their own regional bubbles without some kind of nosey outside influence. Everything now seems so knowing and pre-ordained. But I’m sure there are cool 'yoof' scenes occurring somewhere.”

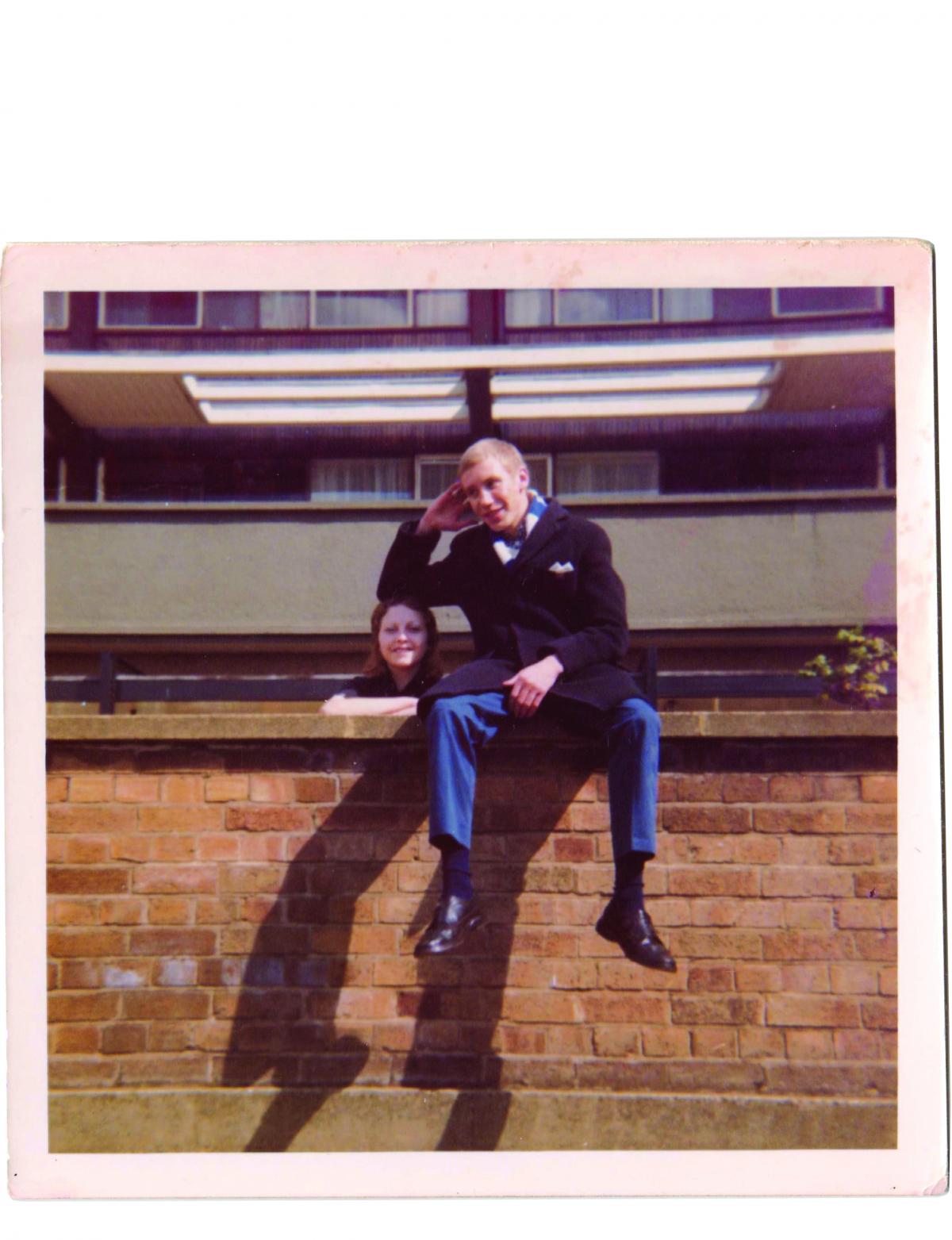

But perhaps the book's greatest triumph is the treasure trove of private photographs Knee has amassed. Turn a page and here's a snap of a Suedehead called Glen sitting on a wall in Great Yarmouth wearing a Crombie coat, blue and white football scarf, Sta Prest trousers and black brogues. Turn again and here's an exterior of Radar, one of the UK's first vintage shops and a Mecca of sorts for those on the Rockabilly scene of the early 1980s. Flip, which would eventually open stores in Edinburgh and Glasgow, was another which catered to the scene by importing cheap 1950s clothes from America that would otherwise be turned into rags.

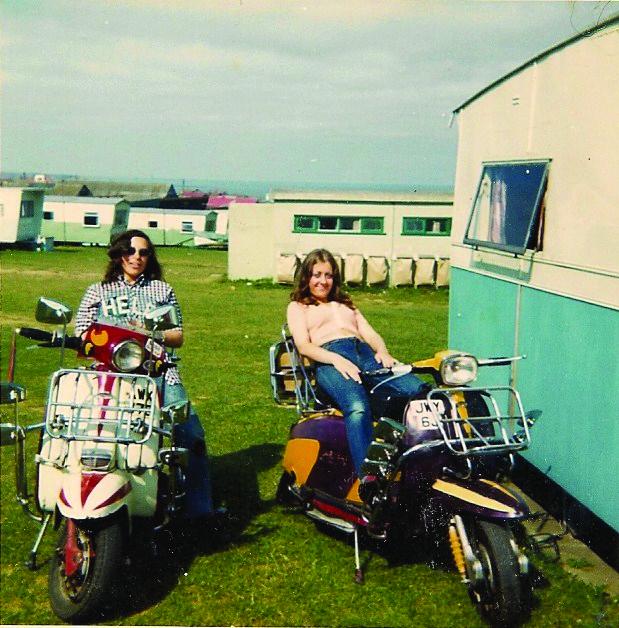

Here are young people at all-nighters in Wigan, and all-dayers in Norfolk. In front gardens and back bedrooms. On council house balconies in Manchester holding David Bowie albums below feather-cut hairdos, on south coast seafronts in dungarees and sandals, posing on mopeds in a Bradford trailer park.

And here are grinning “ton up” boys Michael and Derek in a bent and creased black and white snap taken in Yarmouth in 1962. Helmets in hand and fishermen's socks turned over the top of their motorcycle boots, one wears a Lewis Bronx biker jacket, the other a Belstaff Trialmaster. Where are they now? Behind them the Yarmouth Aquarium advertises a concert by Billy Fury. You don't hear him much these days, but Belstaff are still around and if you've got a spare £600, a Trialmaster can be yours.

“I love all these grainy old snaps and crinkled up barely visible Polaroids,” says Knee. “To me they’re magical and real, warts and all. In the book I purposefully used amateur snaps taken by real people from within the scenes, rather than some slick pro-photographer material, which more often than not lose all sense of authenticity.”

To access this impressive cache of photographic memorabilia, Knee went as deep as he could into as many of the subcultures as possible. But if there's an unwritten coda to his book it's this: just as photographers fade, so do memories. And so do people.

“The time is now for archiving,” he says simply. “Many of the original scenesters are long in the tooth and not far from the ultimate end. The kind of one-on-one personal communication I had with my elder contributors just won’t be possible in 20 years' time.”

The Bag I'm In: Underground Music And Fashion In Britain 1960-1990 with a foreword by Bobby Gillespie is published by Cicada (£22.95)

Why are you making commenting on The Herald only available to subscribers?

It should have been a safe space for informed debate, somewhere for readers to discuss issues around the biggest stories of the day, but all too often the below the line comments on most websites have become bogged down by off-topic discussions and abuse.

heraldscotland.com is tackling this problem by allowing only subscribers to comment.

We are doing this to improve the experience for our loyal readers and we believe it will reduce the ability of trolls and troublemakers, who occasionally find their way onto our site, to abuse our journalists and readers. We also hope it will help the comments section fulfil its promise as a part of Scotland's conversation with itself.

We are lucky at The Herald. We are read by an informed, educated readership who can add their knowledge and insights to our stories.

That is invaluable.

We are making the subscriber-only change to support our valued readers, who tell us they don't want the site cluttered up with irrelevant comments, untruths and abuse.

In the past, the journalist’s job was to collect and distribute information to the audience. Technology means that readers can shape a discussion. We look forward to hearing from you on heraldscotland.com

Comments & Moderation

Readers’ comments: You are personally liable for the content of any comments you upload to this website, so please act responsibly. We do not pre-moderate or monitor readers’ comments appearing on our websites, but we do post-moderate in response to complaints we receive or otherwise when a potential problem comes to our attention. You can make a complaint by using the ‘report this post’ link . We may then apply our discretion under the user terms to amend or delete comments.

Post moderation is undertaken full-time 9am-6pm on weekdays, and on a part-time basis outwith those hours.

Read the rules here