Excavation work at Ben Cruachan to create a hydroelectricity station began 60 years ago this summer. Sandra Dick looks back at an engineering and construction miracle.

Amid breathtaking Highland scenery, Ben Cruachan stands tall; the highest point in Argyll and Bute and one of a range of jagged peaks stretching between Loch Etive and Loch Awe.

Rock solid and stone cold, it weathered the elements unchanged and unchallenged for 450 million years.

Or, at least it did until 60 years ago this summer, when men with gelignite and ingenious plans set about slicing it open, blasting a huge hole in its belly and drawing power from deep within its rocky soul.

Those who witnessed the engineering and construction miracle that produced the world’s first high-level reversible pumped storage scheme for generating hydroelectricity say the dirt, noise and scale of excavating its innards felt like stepping into the jaws of hell.

But for Scots who had rapidly come to rely on flicking a switch for instant electricity, the newly constructed £24.5 million Cruachan Power Station brought power to the people in hundreds of thousands of homes and businesses.

Construction work on surely the most ambitious manmade project Scotland has ever seen began in mid-1959, and continued even after its official opening by the Queen in 1965.

But while half a century has passed since it first sent hydroelectricity to the National Grid, today’s renewable energy landscape means the almost instant power supplied by the "hollow mountain" is required more than ever.

For should renewable power sources fail and the nation’s lights go out, it will be Cruachan’s steadfast and sure turbines and generators that will be called upon to produce the power that will restart essential services across the land.

And, such is the hydro plant’s ability to produce clean and almost instant power, its current operators have a breathtaking wish list to one day dramatically increase its output and even blast again into that ancient rock to create “Cruachan Two”.

“We’re thinking about it and we would love to do it,” says Ian Kinnaird, head of hydro at Cruachan Power Station’s owner, Drax.

“It’s so expensive but there is lobbying of Government going on to demonstrate the value and how well it compliments renewables. We need to find a mechanism to make it financially viable to build.”

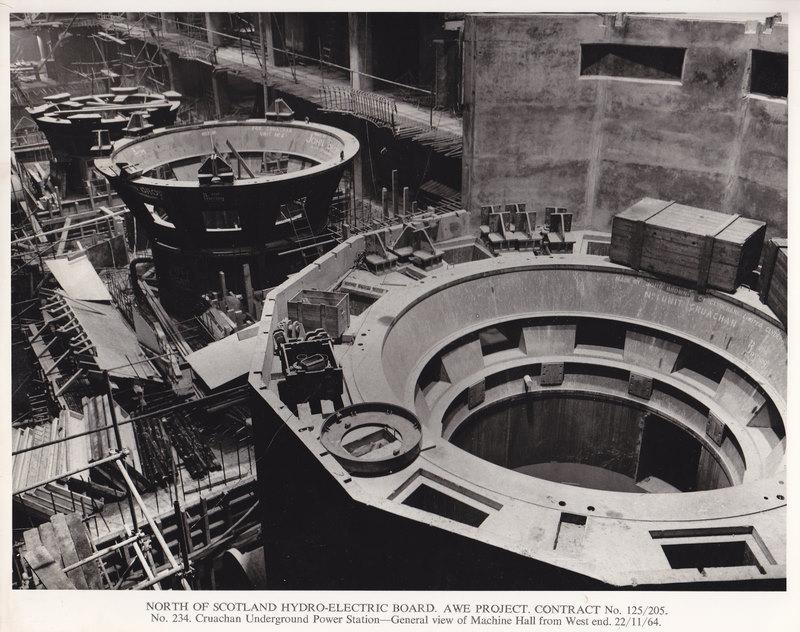

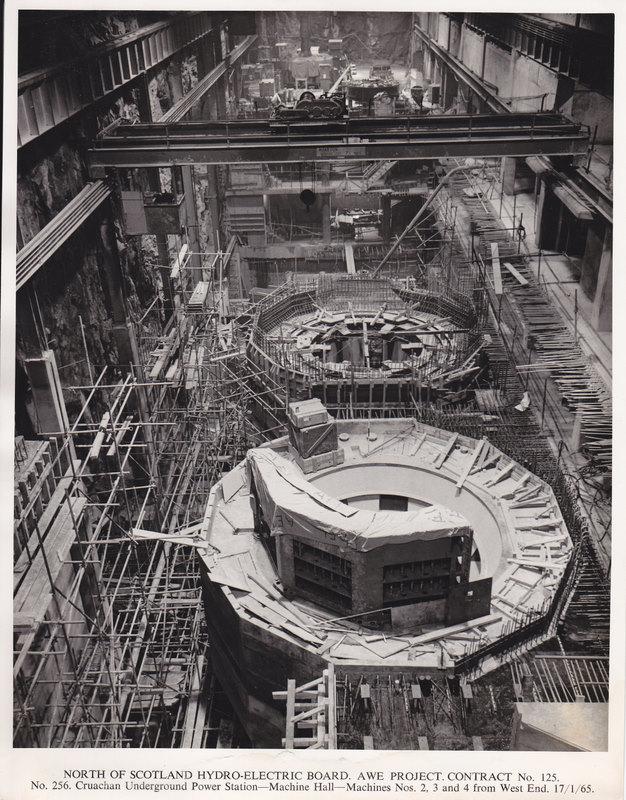

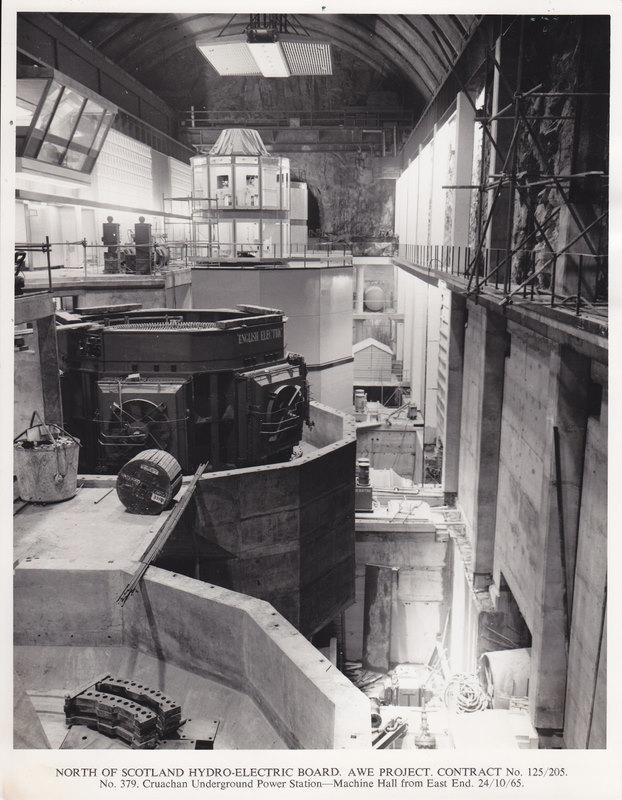

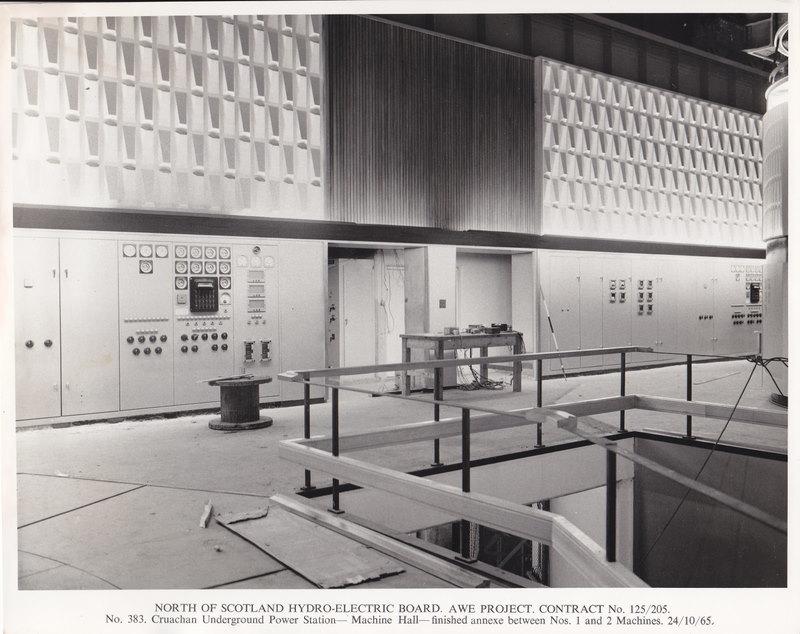

Twenty miles south of Oban and carved from solid bedrock, Cruachan’s cavernous machine hall sits 1km inside the mountain. The size of a football pitch, it is 118ft high, nearly 300ft long and spacious enough to accommodate a seven-storey building.

Conceived by hydroelectricity pioneer Sir Edward MacColl, and engineered by Glasgow-based James Williamson & Partners, its construction saw 220,000 cubic metres of rock and soil scooped from its innards. The task involved around 4,000 workers, many drawn from Ireland by the prospect of high wages, who swapped home for a makeshift camp and back-breaking, filthy 12-hour shifts.

Today the cavern they chiselled from the guts of Cruachan is pristine, home to four generator sets powered by water from a reservoir and Loch Awe, capable of delivering a total of 440 megawatts (MW) of electricity – enough to supply more than 225,000 homes – and flexible enough to power up within seconds, reaching full pumping speed in a mere eight minutes.

For the young Kenny Omond, a Heriot-Watt University electronics engineering student looking for a summer job in 1963, Ben Cruachan’s exposed innards were both terrifying and mesmerising, with conditions that surely no “Cruachan Two” project would ever endure.

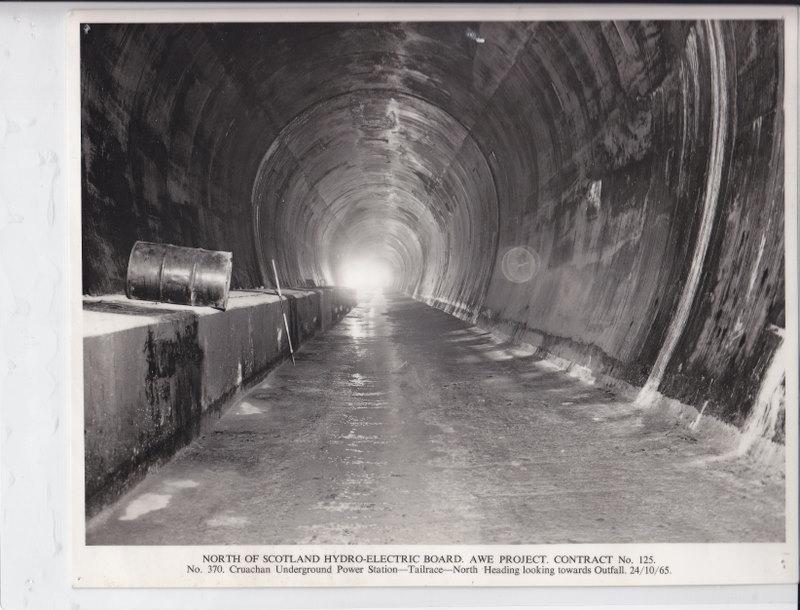

“It was like Dante’s Inferno,” says Omond, 77, from Livingston. “The machine hall was probably as big as St Giles' Cathedral, with little tunnels spinning off.

“There were huge dump trucks going up and down these little corridors. The tyres were eight feet high and the tunnels so narrow that you had to flatten yourself against the walls as they rolled by.”

It was an age, he recalls, when safety gear largely consisted of a hard hat and crossed fingers.

“There was the peaceful beauty of Loch Awe, but inside the mountain the noise was unbearable,” Omond shudders. “There were boxes of gelignite just lying around.”

As well as the cavernous machine room, construction involved 19km of tunnels including two that stretch 400m and at 55-degree angles, and a 316m buttressed concrete gravity dam some 390m up the mountainside. It was not for the faint-hearted; 36 men lost their lives, hundreds of others were injured.

Tunnel Tiger Ian MacLean, 77, of Taynuilt, was a young joiner tasked with shuttering the machine room’s giant horseshoe-shaped concrete roof.

“Dump trucks came from nowhere, they’d appear 10 feet in front of you. The noise was sore on your ears, like a vibration that would go on and on,” he says.

“Me and my mate were working in a shaft that went up to the dam when a chap fell straight down. The guys said afterwards that the oil skins he was wearing had basically held him together.

“It made you wonder what you were doing there.”

Handsome wages provided balance to the gruelling work and the gnawing fear.

“You got an extra shilling an hour if you were working in the tunnel, 2/6 more if you were in the shaft,” adds MacLean. “At the end of the week, I’d have £45 in my pocket – my father in those days was only earning £8.”

Built to support Scotland’s nuclear power stations, Cruachan was intended to operate for short bursts to help juggle increases in demand. These days it is increasingly operating day as well as night.

“The loss of coal-fired plants and the increase of more intermittent renewables such as wind and solar has meant the role of Cruachan and other stations like it have become more important than the original concept,” explains Kinnaird.

“We are seeing a changing landscape. Historically we were generating during the day, absorbing energy and pumping up to the reservoir at night.

“Now if it’s windy during the day, we can be pumping during the day to save energy so the National Grid isn’t having to pay wind farms not to generate.

“When the wind dies down, we can release that energy back to the grid so it’s not being lost.”

In recent years, two of Cruachan’s four generator/motor sets were virtually renewed and output boosted from 100MW each to 120MW. The other two may follow once it’s certain the transmission network can handle the extra load.

But could another project like Cruachan ever be seen again? Executives at Drax Group, which took over the plant and other energy schemes from Scottish Power in a £702m deal, hope so.

They have already embraced proposals – originated by Scottish Power – to boost Cruachan through additional turbines which would boost output to 1,000MW, or the construction of a new dam. Environmental studies are under way to assess the impact of further excavation of the mountain.

“We have outline plans for Cruachan Two, but the capital costs of excavating inside a mountain and building another plant are very, very high,” says Kinnaird. “But we’re thinking about it. And we would love to do it.”

Why are you making commenting on The Herald only available to subscribers?

It should have been a safe space for informed debate, somewhere for readers to discuss issues around the biggest stories of the day, but all too often the below the line comments on most websites have become bogged down by off-topic discussions and abuse.

heraldscotland.com is tackling this problem by allowing only subscribers to comment.

We are doing this to improve the experience for our loyal readers and we believe it will reduce the ability of trolls and troublemakers, who occasionally find their way onto our site, to abuse our journalists and readers. We also hope it will help the comments section fulfil its promise as a part of Scotland's conversation with itself.

We are lucky at The Herald. We are read by an informed, educated readership who can add their knowledge and insights to our stories.

That is invaluable.

We are making the subscriber-only change to support our valued readers, who tell us they don't want the site cluttered up with irrelevant comments, untruths and abuse.

In the past, the journalist’s job was to collect and distribute information to the audience. Technology means that readers can shape a discussion. We look forward to hearing from you on heraldscotland.com

Comments & Moderation

Readers’ comments: You are personally liable for the content of any comments you upload to this website, so please act responsibly. We do not pre-moderate or monitor readers’ comments appearing on our websites, but we do post-moderate in response to complaints we receive or otherwise when a potential problem comes to our attention. You can make a complaint by using the ‘report this post’ link . We may then apply our discretion under the user terms to amend or delete comments.

Post moderation is undertaken full-time 9am-6pm on weekdays, and on a part-time basis outwith those hours.

Read the rules hereLast Updated:

Report this comment Cancel