This week marked the first conviction under Scotland’s new domestic abuse legislation.

The law allows coercive and controlling behaviour, and the impact of abuse on children, to be taken into consideration as an aggravating factor when sentencing is decided. Hannah Rodger speaks to 10-year-old ‘Emily’, a primary school pupil from the west of Scotland, about her experiences of domestic violence, and how this type of abuse can impact children and young people.

“I messaged her saying ‘Mum, the police are coming. Don’t tell him and try and keep the argument going but don’t get really hurt.’ When the blue lights came I was just standing right out the front, saying ‘help’” said Emily, sitting on a big blue chair at the front of her primary school classroom.

The miniature desks and seats usually occupied by her classmates were empty – they had all gone home. As she talked she kicked her legs back and forth, her sandy-coloured ponytail swinging. Looking behind the huge smile, it was impossible to tell the 10-year-old schoolgirl had watched years of horrific domestic violence against her mum and tried her best to stop it.

Like some other fortunate children in Scotland, Emily received help from a pioneering project for children and young people who have experienced domestic abuse. The Children Experiencing Domestic Abuse Recovery (CEDAR) programme works with children as young as four, with several projects operating across Scotland as part of a network. It is thanks to the work of the scheme that Emily is able to talk about the domestic violence she witnessed – which she describes as “home hurting”.

She explained: “The group is for boys and girls who have seen or heard hurting in their family. I would go every week to a little centre and talk about things that had happened.”

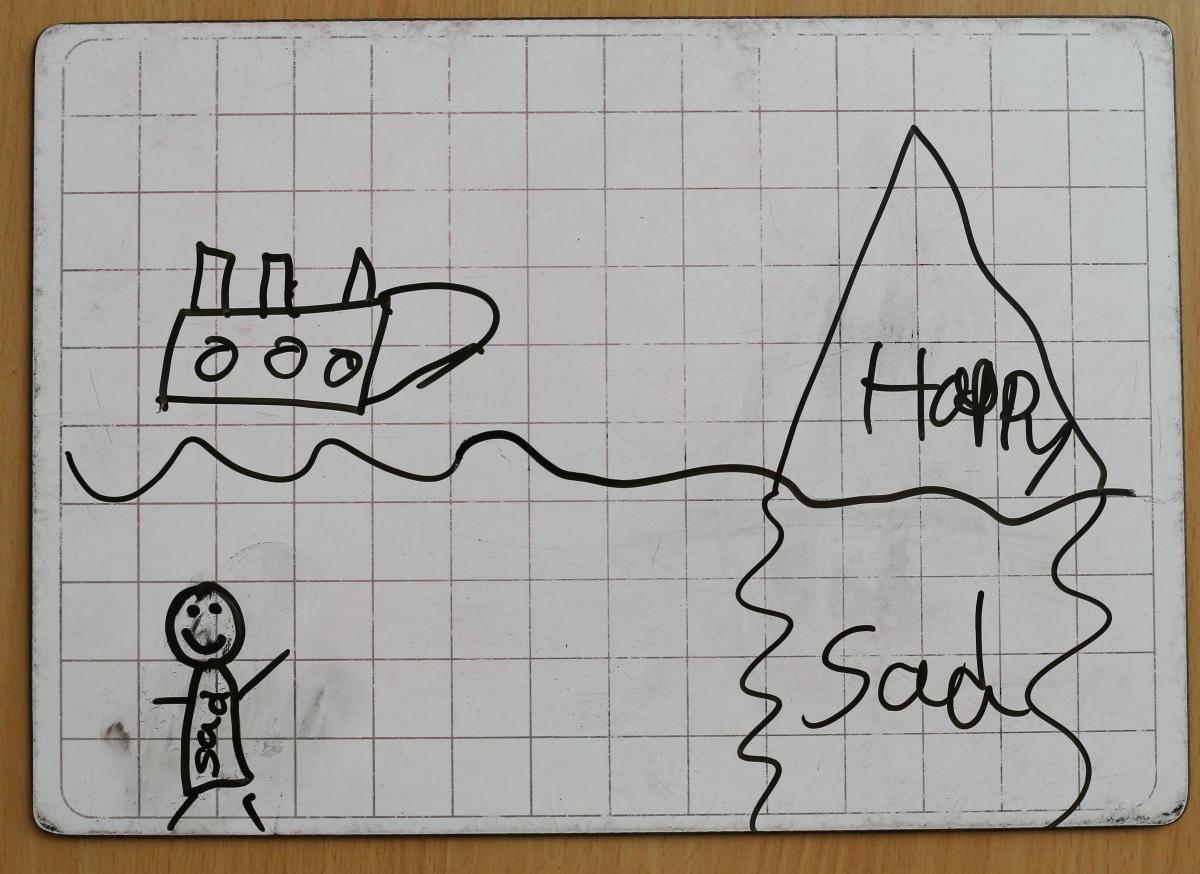

Immediately she sprang up from her chair. She lifted a pen and began to draw on her class blackboard – a big ship with an iceberg in front. Above the water, she writes ‘happy’; below, she scribbles ‘sad’.

“With my iceberg, I looked happy and excited on the outside but on the inside I was actually annoyed, and sad with the home hurting.” she said.

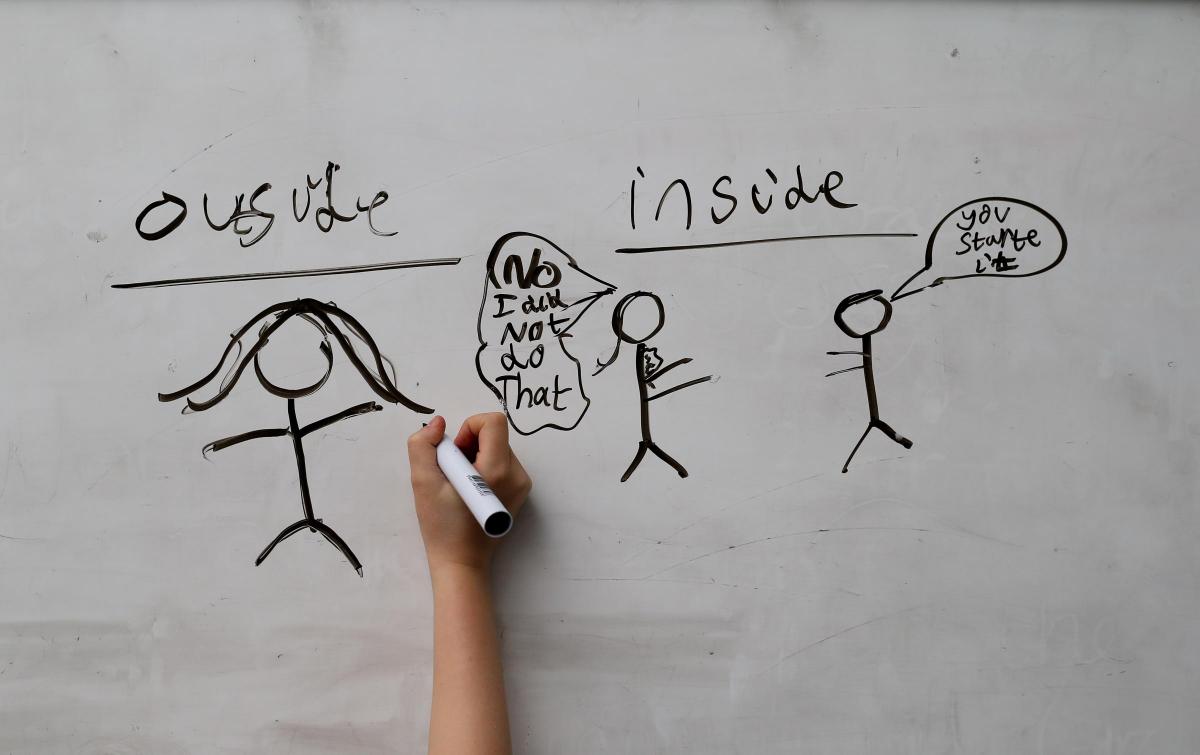

“There was inside and outside hurting for mum.” she explained – referring to emotional and physical violence – when one of the CEDAR workers asked her about the different types of abuse they learned about in their sessions.

Another drawing emerges on the board. She starts with a person in a bed, a living room scene, a man and a smiling woman.

“I’ll make my mum pretty, she’s the nice one” Emily said.

Read More: Domestic violence has 'bigger effect' than any other form of maltreatment

“There was something that happened in my family. I was in bed at the time, trying to sleep. I just heard a lot of like fighting and all that. I was lying there thinking ‘I’m trying to get to sleep’.

“I was really annoyed at my mum, thinking ‘Why, mum, are you letting this happen?’

“I walked to the living room, about 1,2,3,4,5,…10 steps away. I seen my dad shouting and it was really loud. He said a bad word, and after that he was pointing to the door that was leading into my bedroom. I was peeking through the door to see what was happening.

“My mum said ‘no this is my home’. She was pointing to the door that led out the front of the house.

“When it was happening, I was sad, annoyed. I was scared at one point too, but I didn’t tell anyone that.

“I came out of my room I came toddling out and I stopped because I heard this big bang. It was quite loud, it gave my mum a fright too.”

During the incident, Emily said one of her treasured cups which she was given as a young child had been smashed – her stepfather had thrown it against a wall, she explained, as she drew every broken piece of it on the blackboard. It wasn’t the first time something like this had happened, but it is the incident she remembered most vividly.

“It was Friday night, and the next day me and my mum fixed it and we’d never fixed anything before so it turned out really well. It was really fun fixing it together,” she said, smiling.

Emily went on to describe her safety plan, which she devised with two CEDAR workers, about who she would call if she needed help, where she would go to keep safe, and how she could protect her mum.

Her matter-of-fact explanation is hard to listen to, but it is stark reality of life for children living with domestic violence. Hundreds of young people just like Emily have the same plan, written out on a piece of paper, ready to consult when they need to.

She said: “I made a list of people who you could actually trust and go to and tell. Then if something did happen but it was far bigger and you didn’t know if you could trust any of those people, I wrote down who I would tell then. One of mine was my gran and my granddad.

“Then if I was in the house and my phone had died and couldn’t contact anyone I would use my mum’s phone and dial 999, and just say there was a fight happening or…me and my mum did actually call the police before.

“I would say to the police ‘my mum and dad are fighting. I’m really scared’ and ask them nicely if someone can come.”

For protection, she had identified a cubby hole in her house where she would hide there and plan her next move.

She said: “If the fight is still going on and you feel ‘I’m really scared and I don’t know what to do… should I try and stop it while I’m waiting for the police?’ then there was a little place in my house and nobody knew how to get into it except me.

“It was behind my sister’s cot, there’s a little light, and I took some books that I liked reading.

“There’s a plug and my cable can fit through the door. I’d plug my phone in and charge it, then I would message mum because she always has her phone beside her, and tell her ‘Mum, the police are coming. Don’t tell him and try and keep the argument going but don’t get really hurt. If I did say that she would respond saying ‘okay’. When the blue lights come, and then the car comes…I was just standing right out at the front, saying ‘help’.”

Emily has moved to a new flat now with her mum and siblings, and her stepdad has a no-contact order banning him from coming near the family. She has friends, supportive grandparents and is positive about the future. Her experience of domestic abuse, she said, isn’t one that will change the rest of her life.

*Emily’s name has been changed to protect her identity.

Why are you making commenting on The Herald only available to subscribers?

It should have been a safe space for informed debate, somewhere for readers to discuss issues around the biggest stories of the day, but all too often the below the line comments on most websites have become bogged down by off-topic discussions and abuse.

heraldscotland.com is tackling this problem by allowing only subscribers to comment.

We are doing this to improve the experience for our loyal readers and we believe it will reduce the ability of trolls and troublemakers, who occasionally find their way onto our site, to abuse our journalists and readers. We also hope it will help the comments section fulfil its promise as a part of Scotland's conversation with itself.

We are lucky at The Herald. We are read by an informed, educated readership who can add their knowledge and insights to our stories.

That is invaluable.

We are making the subscriber-only change to support our valued readers, who tell us they don't want the site cluttered up with irrelevant comments, untruths and abuse.

In the past, the journalist’s job was to collect and distribute information to the audience. Technology means that readers can shape a discussion. We look forward to hearing from you on heraldscotland.com

Comments & Moderation

Readers’ comments: You are personally liable for the content of any comments you upload to this website, so please act responsibly. We do not pre-moderate or monitor readers’ comments appearing on our websites, but we do post-moderate in response to complaints we receive or otherwise when a potential problem comes to our attention. You can make a complaint by using the ‘report this post’ link . We may then apply our discretion under the user terms to amend or delete comments.

Post moderation is undertaken full-time 9am-6pm on weekdays, and on a part-time basis outwith those hours.

Read the rules hereLast Updated:

Report this comment Cancel