LONG before Neil Armstrong left that first footprint on the lunar surface, on July 20, 1969, ordinary people were signing up for the first commercial flights to the Moon.

The story goes that in 1964 an Austrian journalist walked into a travel agency in Vienna and asked about visiting the Moon. Pan Am airlines – probably not entirely seriously – took the reservation, and the journalist paid a deposit roughly equivalent to twenty dollars. The story attracted headlines, and Pan Am, knowing good publicity when it saw it, launched its First Moon Flights Club. Official cards were issued to members.

Pan Am's futuristic space plane Orion III, seen in the 1968 sci-fi classic film, 2001: A Space Odyssey, seemed to bring the prospect of commercial Moon flights ever closer. On July 22, two days after man walked on the Moon, it was reported that some 26,000 people, including 20 Scots, had asked Pan Am and Trans World airlines to book them seats on the first commercial Moon flights.

Pan Am had informed applicants that it had no idea of the cost or other relevant details. "We have always treated the inquiries seriously because there is no telling what will happen,” said a spokesman. In this country, the marketing director of Caledonian Airways said: "We have had a number of inquiries about moon charters, several of them today. We cannot treat them seriously at the moment but it’s good fun.”

By 1971, it's said, an estimated 93,000 people had signed up to go to the Moon.

Herald View: Apollo 11 Moon Landing was humankind's greatest breakthrough, but our next must be closer to home

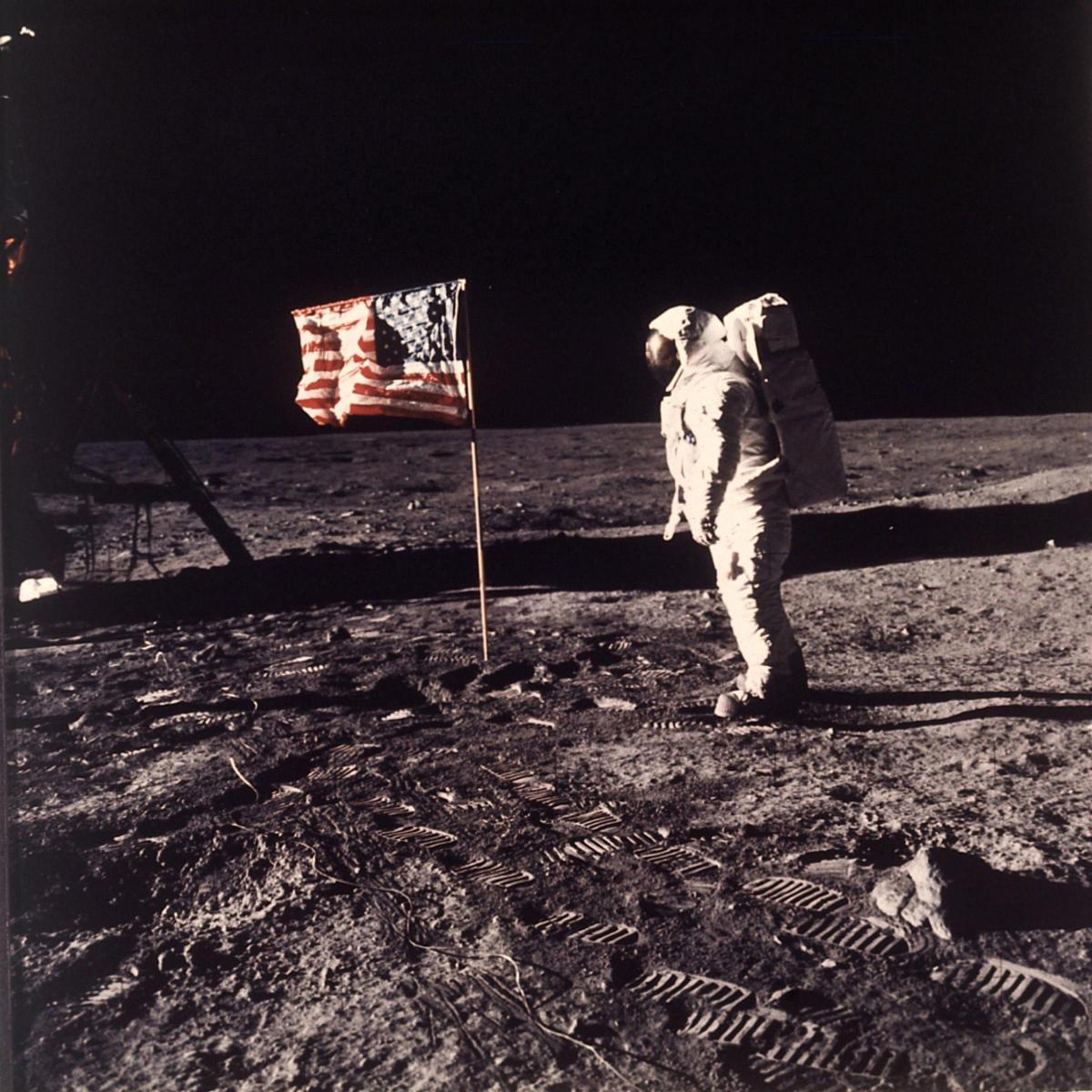

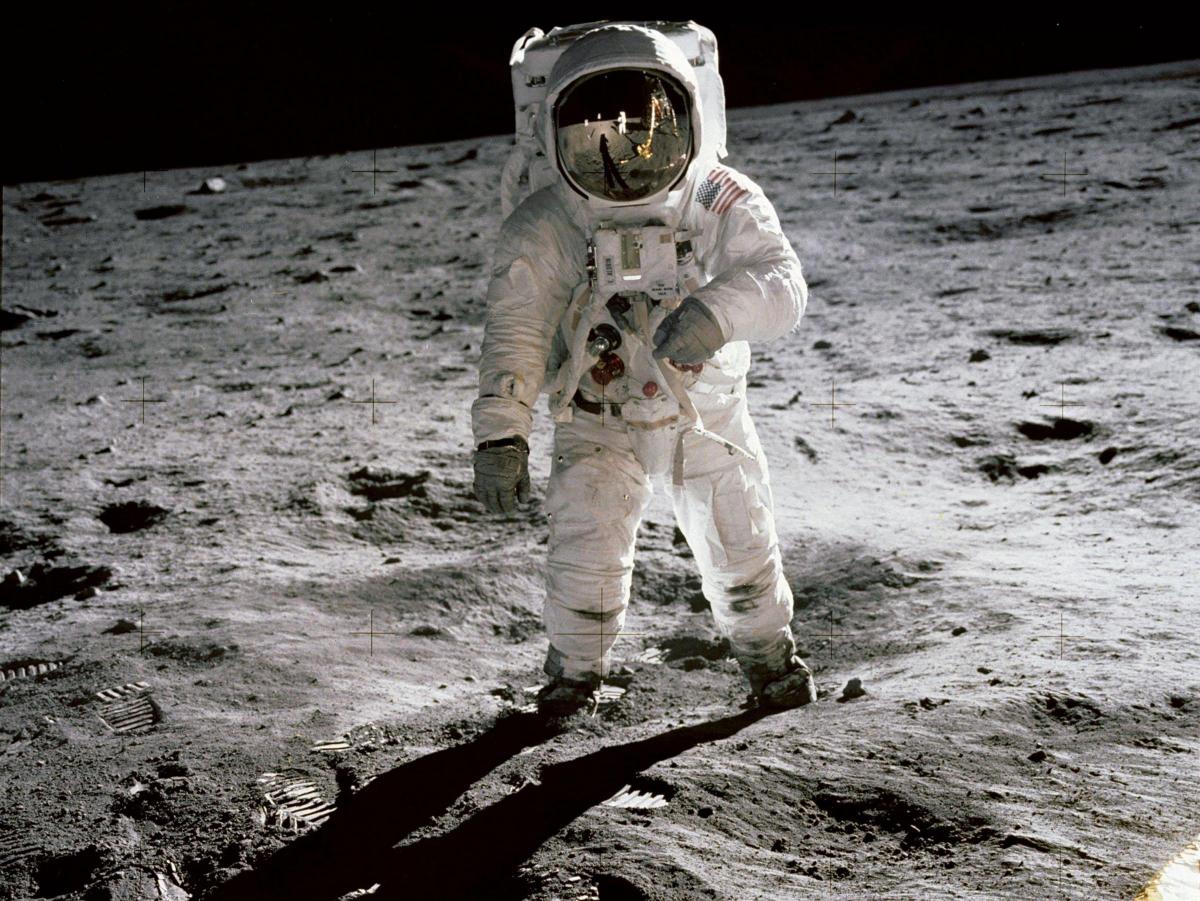

People of a certain age have vivid memories of the achievements of Apollo 11 and its crew, Commander Neil Armstrong, Command Module Pilot Michael Collins and Lunar Module Pilot Edwin "Buzz" Aldrin. Apollo 11 launched from Cape Kennedy on July 16, and when, four days later, Armstrong stepped from the Eagle lunar module with the words "...one small step for a man, one giant leap for mankind," some 650 million television viewers were giddy with excitement. The sense of wonder – that humanity had actually walked on a distant celestial body – was nothing short of profound.

Herald reader Russell Smith relates: "Along with the death of King George V1 when school lessons were stopped in the afternoon for the news, Suez, Bannister’s sub-4 minute mile, and the assassination of President Kennedy, those of my generation (1935), will never forget the amazement at the technological development of the 1969 Moon landing, the pictures, commentary, and the successful return. My elder daughter (1963) just remembers being told, 'You’re going to see something amazing, the man on the Moon'."

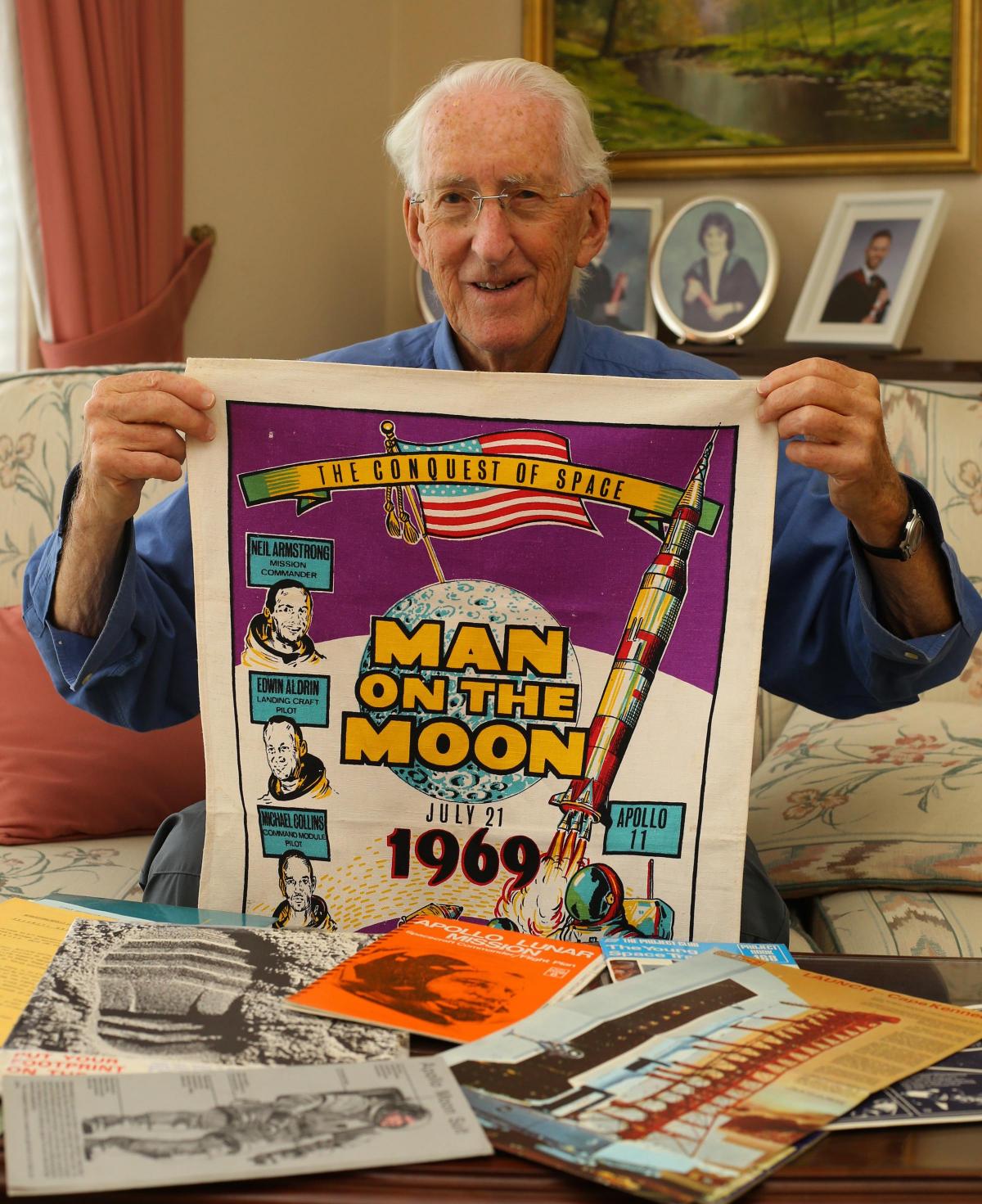

Mr Smith has two interesting souvenirs of that epic time – a Man on the Moon dish-towel, and a special presentation pack, Touchdown on the Moon, which included everything from Apollo 11's flight plan to press briefings, lunar excursion orders and even a 45 record, Man on the Moon, which includes voices of the NASA announcer and the astronauts.

"It was July 1969 and the words, 'This is one small step for man, one giant leap for mankind', were about to become part of modern history," begins Moira Strachan's contribution to Scottish Book Trust’s Stories of Home campaign 2014. "Whenever I hear those words now I am transported back to that time when, strangely perhaps, I shared my home in Greenock with a number of American sailors. No round-the-clock news coverage then: only the print headlines, the radio and the 6 o’clock news, but the air was ringing with the sounds of whooping and hollering as they celebrated, loudly and patriotically, Neil Armstrong’s achievement of being the first man to step on the moon."

Strachan, who is now retired, was 15 then: home was the Inverclyde Sailors’ Centre on Dalrymple Street, where her father was the manager. Around 30 Americans lived there while their Holy Loch base across the Clyde was being refurbished.

"The excitement of the Moon landing stretched over several days," recalls Herald reader Gordon Casely. "I worked for Evening Express in Aberdeen and – unusually for an evening paper – news of the moonshot and subsequent landing appeared on Page 1 across all of our editions. I happened to be at home during the actual landing, listening to live coverage on the radio, and well recall Neil Armstrong’s words crackling over my bonnie big multi-valve radio. So thrilled was I that I phoned my parents in Edinburgh, and held the phone to the radio so that they could hear voices all the way from space.

"For us on the paper," he adds, "the Moon landing had all hands to the plough. When news broke early one afternoon that the astronauts were having difficulty sleeping in their capsule, editor Bob Smith re-plated Page 1 halfway through the final edition print-run. Thus the paper landing on the streets for the five o’clock homeward rush bore the single heading 'MOONSOMNIA!'"

In the early hours of the 21st, the Glasgow Herald had acute problems with deadlines for its first edition. In his history of the paper, Alastair Phillips says everything was in place, including a banner headline, Man lands on the Moon. The start-button just needed to be pressed that would get the presses rolling. But Armstrong, writes Phillips, 'was being unconscionably slow about coming down the ladder. Until he set foot on the Moon, the chief sub-editor had the incongruously attentive but far-away look of the man who was mulling over the possibility of a more depressing headline and opening paragraph.'

Herald View: Apollo 11 Moon Landing was humankind's greatest breakthrough, but our next must be closer to home

The machine-room manager warned the editor, Alastair Warren, that he could only give him another five minutes, otherwise the edition would not go out in time and would miss distribution vans. Armstrong remained poised on the ladder, six feet above the surface. The Herald staff were getting desperate. Phillips himself said the presses should roll, 'but not a single copy must leave the place until you get the all-clear from this phone'. The presses were picking up speed when Armstrong stepped off the ladder.

The updated headline for the second edition read, MAN WALKS ON THE MOON: Astronauts go exploring after perfect landing in Sea of Tranquillity, alongside an artist's impression of Armstrong on the lunar surface.

"A new age dawned at 3.56am yesterday morning when Neil Armstrong stepped on to the Moon," began the Herald leader on July 22. "Historians may judge that modern times have ended, and the space age has begun."

“I was 15 when the first manned Moon landing took place," says the Rt Rev Colin Sinclair, the current Moderator of the General Assembly of the Church of Scotland. "I remember being allowed to stay up very late to watch it happen.

“It was nearly 3am before Neil Armstrong put his foot on the surface of the Moon. I was very tired but it was all very exciting. His well-known words, "one small step for man, one giant step for mankind" were actually quite difficult to hear and their impact only came later when they were repeated the following morning on the news.

“At the time you felt that human beings could do anything they set their minds to. We thought that was the beginning of the exploration of the planets. Sadly, three years later, the whole project would stop.”

This memory, from Basia Palka from Poznan, Poland, comes courtesy of the Glasgow Science Centre, which is staging several special events to mark the 50th anniversary. "I arrived in Scotland in 1969 after being put on a train in Poznan aged 10 by my grandfather. I travelled to the UK by myself and was met at Harwich by my mum whom I had not seen for two years. I was brought to a single end in the Gorbals.

"We had a black-and-white TV and on the day of the Moon landing some of the neighbours piled in to the one room to watch this bit of history in the making. At that point in time I had no English but I understood that this was an amazing moment.

"I was in empathy with the astronauts who had taken such a trip as I felt that I, too, had taken an enormous journey to get here to Glasgow all by myself with a name tag round my neck, not unlike Paddington Bear.

"I remember it well when I had put my foot down on British soil for the first time as I watched the first astronaut putting his foot down on the surface of the moon.We had this much in common; we had taken a ginormous journey.Theirs had been a bit longer than mine."

Dr Alistair Ramsay MBE remembers: "I was a student working as a silver-service waiter in the Atholl Palace Hotel in Pitlochry. "Normally the waiters ate their meals in one part of the hotel but the ‘blue’ staff (gardeners, chambermaids, handymen, etc) had their own dining room and they got chips. Waiters normally weren’t allowed into the blue staff dining room but I had started in the hotel as a kitchen porter before being promoted to the dining room, so I was allowed in. On the day of the Moon landing I went to the blue staff dining room and watched "one small step for man, one giant leap for mankind," while stuffing my face with chips. A big argument was raging about whether or not it was a massive con but watching on a black and white TV it was still very impressive!"

Scots-born former airline pilot Bill Innes, author of Flight from the Croft, remembers: "Like all pilots I was fascinated by the Moon landing and watched as much as I could on the ghostly telly pictures of the time. It is absolutely amazing what was achieved with the primitive computers of those days. Eight years later I had the privilege of watching a (much smaller) Delta rocket launch a satellite from Cape Canaveral and that was impressive enough. The Americans had every right to have their breasts swell with patriotic pride."

He added: "Even in 1982 when the first glass cockpit B757s and 767s appeared, their computer power was a fraction of that of a modern smartphone. The only advantage my job gave me was that a darkened cockpit is a great place to catch satellites and space stations tracking across the night sky."

Another Herald reader, Sandy, from Stirling, who is in his eighties, says: "I remember sitting in the lounge of the old Golf Hotel in Elie, watching a small television screen with all the other guests and my wife and little daughter around midnight that day. My wife was pregnant with our son and at that time she had thoughts about calling him Neil."

In the event, they went with another name, but some couples were sufficiently inspired by the Moon landing to christen a new-born after one of the astronauts, among them a couple in Monifieth, who named their son after all three. A couple in Toledo, Ohio, christened their new baby boy Neil Armstrong. Their surname? Moon.

It is fair to say, however, that not everyone was overwhelmed by what happened in July 1969. Herald reader Thelma Edwards remembers that she shunned the entire event: "I refused offers from family members to view the whole thing on their TV sets. This was all due to what had happened to Laika, the dog that Russia sent into space in 1957. She died very soon after the launch and I was steaming mad. What right had we to use animals for these purposes? Perhaps if what happened to Laika, and several other animals, hadn’t happened I might have felt differently about the whole thing. We have made a mess of this planet so we should stay on it and put it right, not go spreading our mess on other planets. I subscribe to the ideas in James Lovelock’s book Gaia – The Practical Science of Planetary Medicine.

As much as the Moon landing dominated the newspapers (and TV and radio, of course), space still had to be found for other stories, from home and abroad: the incident at Chappaquiddick, Massachusetts, when a car driven by US Senator Teddy Kennedy plunged off a bridge, and his 28-year-old passenger, Mary Jo Kopechne, died trapped inside the vehicle.

In Glasgow, there were 600 arrests on the first day of the Glasgow Fair (police said such a start was normal, or even quieter than usual). Police were investigating the murder of 72-year-old Rachel Ross, in an armed robbery in Ayr. Police wanted to interview James Griffiths in connection with her death, but he went on a rampage, shooting and wounding 13 people (one of whom died, on July 21) before being shot dead by a police officer. Paddy Meehan was subsequently convicted of murdering Mrs Ross, but he received a royal pardon in 1976.

Jackie Stewart won the British Grand Prix, just 24 hours after a 130mph crash in practice. He went on to become world champion that year.

In Scottish cinemas, the big movies included The Love Bug, Oliver!, Oh! What a Lovely War, and Ring of Bright Water. Top-selling singles that week included Thunderclap Newman's Something in the Air and The Rolling Stones' Honky Tonk Women. Construction of Glasgow's Kingston Bridge was well underway. Bible John's second victim, Jemima McDonald, would be found dead in August.

Dr Archibald B Roy, then a senior lecturer in astronomy at Glasgow University, won £1,200 as a result of an £8 Moon-landing bet he had made on a visit to America five years earlier. A 26-year-old in Preston won £10,000 on a similar 1,000-to-1 bet. Betting odds shortened dramatically on there being a manned landing on Mars before 1972. Postcards franked at Cape Canaveral on Apollo 11's blast-off day sold out in Britain. “We' have been overwhelmed with the demand,” said the marketing manager at John Menzies & Co, in Edinburgh.

The landing, and Armstrong and Aldrin's walkabout, received substantial coverage on the BBC and ITV. Six South Africans paid £250 each to travel to London to watch the broadcasts. Crime in Italy during the night dropped to one-third of its normal levels. ITV's Man on the Moon programme, a seven-hour-long special fronted by David Frost, included entertainment spots from, amongst others, Lulu and Engelbert Humperdinck. Three days after the Moon landing, a number of people had to be rescued when their cabin cruiser, Apollo, got into difficulties in the Firth of Forth.

After Armstrong and Aldrin, 10 other astronauts – Pete Conrad, Alan Bean, Alan Shepard, Edgar Mitchell, David Scott, James Irwin, John Young, Charles Duke, Eugene Cernan, and Harrison Schmitt – walked on the lunar surface. Of the 12, just four are alive: Aldrin, Scott, Duke and Schmitt. But public and political fascination with deep-space exploration quickly faded.

As The Herald noted on the 10th anniversary of Apollo 11, the topic suffered a "drastic loss of interest and funds after 1969, because it was then only a propaganda extravaganza with very limited practical benefits." Priorities suddenly, decisively, lay elsewhere: inflation, urban riots, the closing stages of the Vietnam war, the Middle East war, oil prices, Watergate.

Herald View: Apollo 11 Moon Landing was humankind's greatest breakthrough, but our next must be closer to home

In recent months, however, interest has been revived in the Moon. In January this year, China successfully landed a robotic spacecraft on its far side. In April, an Israeli spacecraft crash-landed on the lunar surface, the first privately funded mission to the Moon. And this weekend, The Indian Space Research Organization's (ISRO) Chandrayaan-2 lunar mission is scheduled to launch; if it goes to plan, it will touchdown on September 6.

And in the longer term? US Vice-President Mike Pence has asked NASA with returning humans to the surface of the Moon by 2024.

Why are you making commenting on The Herald only available to subscribers?

It should have been a safe space for informed debate, somewhere for readers to discuss issues around the biggest stories of the day, but all too often the below the line comments on most websites have become bogged down by off-topic discussions and abuse.

heraldscotland.com is tackling this problem by allowing only subscribers to comment.

We are doing this to improve the experience for our loyal readers and we believe it will reduce the ability of trolls and troublemakers, who occasionally find their way onto our site, to abuse our journalists and readers. We also hope it will help the comments section fulfil its promise as a part of Scotland's conversation with itself.

We are lucky at The Herald. We are read by an informed, educated readership who can add their knowledge and insights to our stories.

That is invaluable.

We are making the subscriber-only change to support our valued readers, who tell us they don't want the site cluttered up with irrelevant comments, untruths and abuse.

In the past, the journalist’s job was to collect and distribute information to the audience. Technology means that readers can shape a discussion. We look forward to hearing from you on heraldscotland.com

Comments & Moderation

Readers’ comments: You are personally liable for the content of any comments you upload to this website, so please act responsibly. We do not pre-moderate or monitor readers’ comments appearing on our websites, but we do post-moderate in response to complaints we receive or otherwise when a potential problem comes to our attention. You can make a complaint by using the ‘report this post’ link . We may then apply our discretion under the user terms to amend or delete comments.

Post moderation is undertaken full-time 9am-6pm on weekdays, and on a part-time basis outwith those hours.

Read the rules hereLast Updated:

Report this comment Cancel