Personal diaries, photographs and belongings have been retrieved from homes across Scotland to shed fresh light on the First World War, reports Sandra Dick.

Stuffed into boxes, tucked into drawers or shoved at the back of the wardrobe, they have been kept safe for a century, final poignant mementoes of young lives crushed by war.

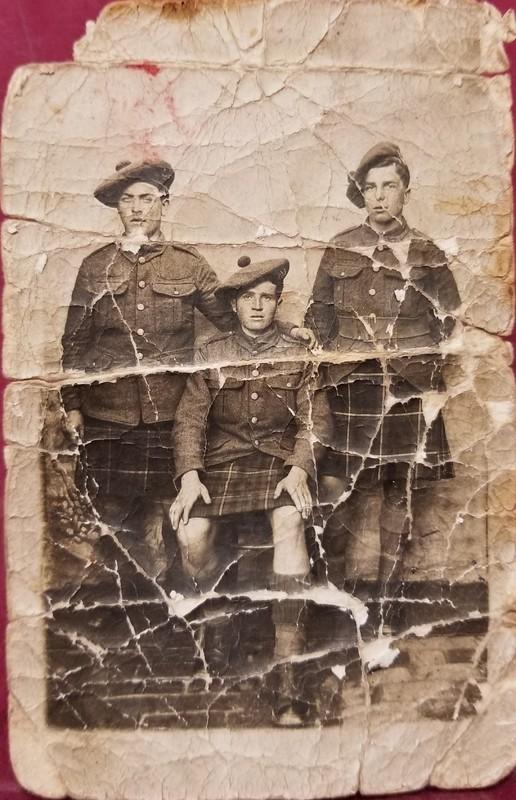

There's the blood-spattered photograph probably tucked into a top pocket close to the heart while the owner marched to battle, a soldier’s tie – its colours every bit as rich and vibrant as the day it was knotted 100 years ago as he prepared to fight at Gallipoli – and countless letters in spidery handwriting that tell of torpedoes and death and hopes that everyone at home is doing well.

And with them, ghostly figures captured in photographs standing proud, pitifully young and about to be propelled into the hellishness of the First World War.

A remarkably touching collection of keepsakes from ordinary Scots families whose lives were shattered by conflict has been gathered from around the country as part of a Commonwealth War Graves Foundation project to uncover a hidden heritage of wartime bits and pieces that have spent decades stashed in homes around the land.

- READ MORE: Scotland's proud history of castles - and now you could own one (if you have a spare £3m)

Each represents a family’s personal reminder, however painful, of pride and love for their lost sons and daughters.

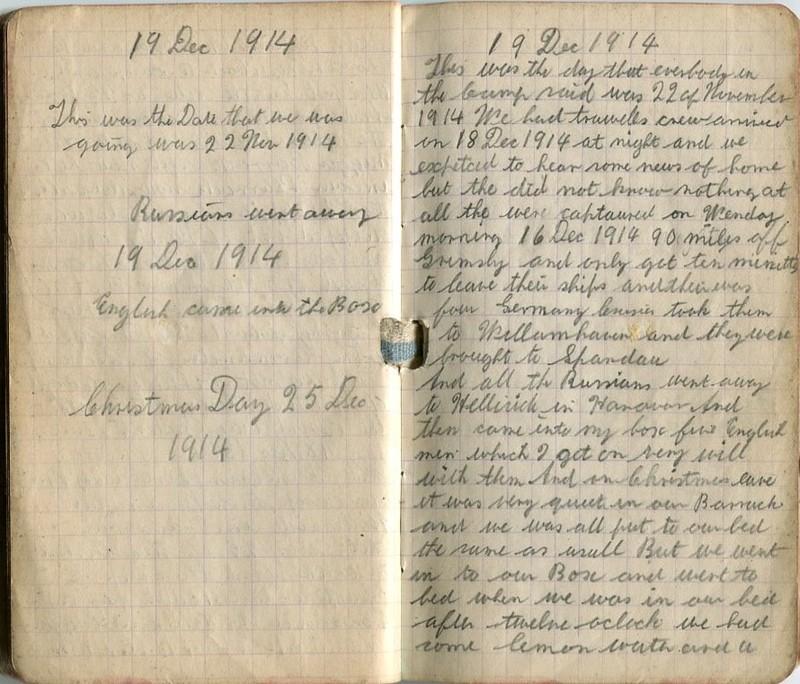

The items gathered during a series of events earlier this year include a Scots soldier’s remarkably detailed diary of life as a Spandau prisoner of war, a sailor’s notes of the moment SS Netherlee was mortally wounded by a U-boat sending the dazed crew into panic, and a young Scots nurse’s collection of war hospital photographs.

Perhaps among the most emotional is a series of letters to and from a desperate Banchory couple informing them their son Bill McLennan – one of their four boys on the Western Front – was at first wounded, then gravely ill and finally dead.

Among them is a heart-wrenching plea from the anxious parents to travel from their Aberdeenshire home to visit him in hospital in France.

“Could you inform me if a pass could be got for me and his mother to visit him in hospital?,” appealed the soldier’s father. “I shall be greatly obliged to you for any information you can give me regarding my boy who has three other brothers fighting in France with him.”

The military reply was a blunt refusal, in stark contrast to the comforting letters sent by nurses battling to save Private McLennan while gangrene consumed his amputated leg.

Their letters spoke optimistically of hopes of his recovery, messages that the couple must have clung to. Eventually, however, they would be among the hundreds of thousands of parents to receive bitterly sad news.

“In spite of all his suffering, he was always bright and cheerful,” wrote one nurse. “We hoped and hoped we would be spared.”

“I would like you to know what a splendid patient he was and how grieved we were to lose him,” wrote another.

Teams from the Commonwealth War Graves Foundation and the University of Oxford photographed 10,000 items from events held around the country. They have now been uploaded to a new digital archive, Lest We Forget.

Max Dutton, assistant historian at the Commonwealth War Graves Commission, said it had uncovered items which might never have been seen outside of individual families.

“Lots of people probably have this stuff hidden at the back of a drawer or in a box in the attic,” he added. “The aim was to get people to bring them out so future generations can see these belongings of a lost generation.”

Some, such as a collection of photographs and papers connected to Private Robert Mackintosh Duncan of the Gordon Highlanders, hint at the tragedies that consumed communities – he was one of 17 young men from the rural community of the Cabrach in Aberdeenshire who never made it home.

A particularly startling image is that of John McCamley from Cowcaddens, Glasgow. Underage when he joined the Cameronians, he is captured looking fresh-faced – little more than a child. He died of wounds on October 15, 1918, just three weeks before the Armistice.

Items worn by soldiers and sailors are particularly poignant, said Dutton. “Each item tells a story of an individual. We had a shaving set brought in with the blades still sharp. It has no monetary value but it tells a story of that individual who took his shaving kit to battle and perhaps never came home to his wife, child or parents.”

- READ MORE: The Treaty of Versailles

Likewise, the Royal Scots tie worn by boy soldier Robert Pringle Lothian as the 16-year-old fought in Gallipoli, where he was shot through the arm. He was later killed fighting in the Second World War, at the age of 42.

The tie and his photograph are among the few items that his then 10-year-old daughter, Patricia, was left to remember him by.

Dozens of diaries and letters, creased and faded by the passing years, were recovered from drawers and boxes where they have lain for years and are included in the new archive.

They shed light on life at the front, from upbeat messages which disguise the horrors of war to stark descriptions of battle, prison and lives cruelly cut short.

“On Christmas Eve we were all put to our bed the same as usual,” wrote Alexander Mackie, who was on board a vessel captured by Germans a day after war had been declared, and who was held in notorious Spandau prison.

“After twelve o’clock we had some lemon water and biscuits and cakes and sang songs and made a little noise,” he wrote.

“One of the soldiers in charge of our barrack got drunk and we had some fun with him,” he added, going on to tell how the soldier, nicknamed The Bishop, spilled his beer, dropped cigarettes and knocked over lit candles. “He gave us a speech about the war in Germany, and that he wished the war was over,” he added.

Spandau prisoners were given a Christmas dinner of a chop, potatoes and a bottle of beer, with a cigar and a packet of sweets as an extra treat.

Another letter, written by John Smith from Rutherglen, a Lance Corporal with the Seaforth Highlanders, described the Battle of Loos.

“At half past six on the morning of 25th September the order passed down the line ‘Up boys and away with the Goalie’,” he wrote. “Like one man we were over and charging.

“Comrades fell but on we went capturing four lines of trenches and a village behind them. We had some exciting fighting to do in the cellars and back gardens of the houses.”

He said any who refused to surrender “were either given a bomb to divide among them or a few lead pills”.

The letter describes how he was wounded days later. “When I came to, someone was tying a bandage around my napper. I had a marvellous escape.”

However, his time was running out. He later died of injuries sustained at the Battle of the Somme.

Dutton said the items are just a small snapshot of many war mementoes stored by families around the country.

“I would urge people to go and see what’s in the attic and discover the stories of their own family,” he added.

“We should be asking our relations about what happened during the Second World War now.

“We can’t do that for the First World War generation, they have all gone, but perhaps we should be doing that now for the Second World War generation who can tell us why these items they have kept are important.”

Items from the Lest We Forget can be viewed at http://lwf.it.ox.ac.uk/s/lest-we-forget/page/welcome

Why are you making commenting on The Herald only available to subscribers?

It should have been a safe space for informed debate, somewhere for readers to discuss issues around the biggest stories of the day, but all too often the below the line comments on most websites have become bogged down by off-topic discussions and abuse.

heraldscotland.com is tackling this problem by allowing only subscribers to comment.

We are doing this to improve the experience for our loyal readers and we believe it will reduce the ability of trolls and troublemakers, who occasionally find their way onto our site, to abuse our journalists and readers. We also hope it will help the comments section fulfil its promise as a part of Scotland's conversation with itself.

We are lucky at The Herald. We are read by an informed, educated readership who can add their knowledge and insights to our stories.

That is invaluable.

We are making the subscriber-only change to support our valued readers, who tell us they don't want the site cluttered up with irrelevant comments, untruths and abuse.

In the past, the journalist’s job was to collect and distribute information to the audience. Technology means that readers can shape a discussion. We look forward to hearing from you on heraldscotland.com

Comments & Moderation

Readers’ comments: You are personally liable for the content of any comments you upload to this website, so please act responsibly. We do not pre-moderate or monitor readers’ comments appearing on our websites, but we do post-moderate in response to complaints we receive or otherwise when a potential problem comes to our attention. You can make a complaint by using the ‘report this post’ link . We may then apply our discretion under the user terms to amend or delete comments.

Post moderation is undertaken full-time 9am-6pm on weekdays, and on a part-time basis outwith those hours.

Read the rules here